There are vanishingly few twentieth-century conductors of classical music whose names have become household words. Perhaps foremost among those few is Arturo Toscanini. There will be objections, I’m sure — Stokowski has a strong following (as well as film credits), as does Koussevitsky, not to mention Leonard Bernstein, Herbert von Karajan and Sir George Solti from the latter half of the century. But, whatever the objections and votes for favorite sons, the name “Toscanini” not only stands out but has come to denote the archetype.

There are vanishingly few twentieth-century conductors of classical music whose names have become household words. Perhaps foremost among those few is Arturo Toscanini. There will be objections, I’m sure — Stokowski has a strong following (as well as film credits), as does Koussevitsky, not to mention Leonard Bernstein, Herbert von Karajan and Sir George Solti from the latter half of the century. But, whatever the objections and votes for favorite sons, the name “Toscanini” not only stands out but has come to denote the archetype.

The legend of Toscanini springs from a remarkable career. He was one of the first to bring order to what had been the sometimes barely restrained anarchy of the nineteenth-century European orchestra, demanding, for example, that all the instruments be in tune and that the performers all play at the same tempo, somewhat revolutionary concepts for the time. He was also a man of passionately held convictions, refusing to perform in Germany or Italy after 1932, traveling to Palestine in 1936 at his own expense to conduct a new orchestra composed largely of Jewish refugees from Central Europe, and in 1938 withdrawing from the Salzburg Festival and lending his efforts to the creation of the Lucerne Festival instead.

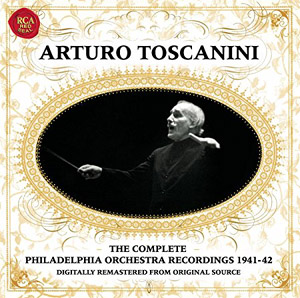

From these examples, it is easy to think of Toscanini as fierce and somewhat uncompromising, and to a certain degree this is true, but there’s another side to him as well. This release was recorded during his second season with the Philadelphia Orchestra (he had traded places with Leopold Stokowski in 1930, Stokowski taking the helm at the New York Philharmonic for the season; those performances, alas, don’t seem to have been recorded) and displays another side of his genius. I’ve mentioned before the truism that each major orchestra has its own sound: Chicago is substantial and majestic, New York lighter and more energetic, Cleveland crisp and clear (as befits what was at one point the premier Mozart orchestra in the U.S.), Amsterdam mellow but precise, Berlin intense and lean, and Philadelphia lush and sensuous. That Philadelphia sound comes through on this collection, but at the same time, it is cleaner, clearer, with a unity of attack and a tensile strength in the playing that are remarkable. It’s obvious that Toscanini had an effect on the orchestra, and equally obvious that he respected the orchestra’s unique identity.

Also characteristic of Toscanini, and readily apparent in this collection: unlike most Italian conductors of his generation, he was eager to perform works by composers of other nationalities (the only Italian that appears here is Respighi) and was also open to works by “contemporary” composers (in this case, Strauss, Respighi, and Debussy). Not only was he catholic in his tastes, but he was able to find the essence of each piece — the Schubert “Great C Major” Symphony is undeniably Schubert, with that lilting drive that is so characteristic, but Toscanini has retained a Germanic gravity that often is lost. (American composer Ned Rorem designated Schubert as “French” and Berlioz, also included on this release, as “German.” That makes a certain sense, but Toscanini managed to subvert that, too.) Likewise, Strauss’ Tod und Verklärung (“Death and Transfiguration”) not only reveals all the dramatic tension that Strauss put into his writing, but a lyricism that all too often is missing in performances of his works. I could go down the line, noting in each work how Toscanini has remained true to its essential nature and yet also found some new quality that further illuminates it — the moodiness of Debussy’s La Mer offset by an amazing clarity, or the almost fevered brightness of Mendelssohn’s Incidental Music to A Midsummer Night’s Dream that yet retains a strong narrative structure — it suddenly makes more sense. It’s a refreshing experience to hear these mostly familiar pieces given a new slant by a conductor who far predated my experience in classical music. Yet another reason to thank Mr. Edison for the magic of sound recording and Maestro Toscanini for making use of it.

The original recordings have been digitally remastered for this collection, and the sound quality is very high. What is especially nice, though, is being able to have a first-class recording of history: a great conductor leading one of the world’s great orchestras.

The works included are: Franz Schubert, Symphony No, 9, D944, “The Great C Major”; Richard Strauss, Tod und Verklärung, Op. 24; Claude Debussy, La Mer and Ibéria; Ottorino Respighi, Feste romane; Hector Berlioz, Roméo et Juliette Op. 17, and Scherzo: “Queen Mab”; Felix Mendelssohn, Incidental Music to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Opp. 21 & 61; Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Symphony No. 6, Op. 74, “Pathétique.”

(Sony BMG Music Entertainment, 2006)