You don’t hear that much Art Pepper these days, even if you listen to a lot of jazz, as I do. When he does crop up it’s usually his 1950s work, when he was renowned for his smooth tone and melodicism. The alto saxophonist spent parts of the 1960s and ’70s in prison and in rehab for his drug addictions. He restarted his career late in the ’70s, though, and the publication of an autobiography penned with the assistance of his wife Laurie Pepper rekindled interest in him as a player. A string of successful dates at the Village Vanguard in 1977 set him back on the path and he was still at the top of his powers at the time of his death at age 56 in 1982.

You don’t hear that much Art Pepper these days, even if you listen to a lot of jazz, as I do. When he does crop up it’s usually his 1950s work, when he was renowned for his smooth tone and melodicism. The alto saxophonist spent parts of the 1960s and ’70s in prison and in rehab for his drug addictions. He restarted his career late in the ’70s, though, and the publication of an autobiography penned with the assistance of his wife Laurie Pepper rekindled interest in him as a player. A string of successful dates at the Village Vanguard in 1977 set him back on the path and he was still at the top of his powers at the time of his death at age 56 in 1982.

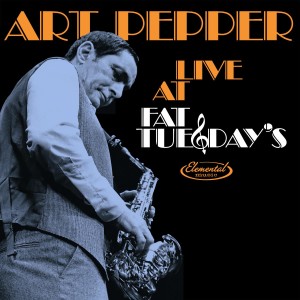

Elemental Music recently resurrected previously unknown recordings from a date by Pepper’s quartet at the New York jazz club Fat Tuesdays in the spring of 1981, assembled with the help of his widow. Art Pepper at Fat Tuesday’s reveals a true original in top form, one who combined lyrical ballad work, straight-ahead bop, and Coltrane-influenced avant garde in a way I’ve heard nobody else do on the horn.

The date consists of only five numbers, but each one is an extended workout for the Californian and his ensemble: long-time associate Milcho Leviev on piano and New York guests bassist George Mraz and drummer Al Foster. It kicks off with a faster-than-normal rendition of Thelonious Monk’s “Rhythm-a-ning,” a brave and canny choice. Pepper had a keen sense of rhythm and understood Monk’s odd rhythms, quirky harmonies and angular phrasing, and this workout gets the audience’s attention right away and holds it. Then he dives into the Cole Porter standard “What Is This Thing Called Love?” and it too is a bit more up-tempo than usual – and aggressive, combining lightning bop runs with post-bop squeals.

Pepper wisely drops a ballad in the middle of the set, a minor standard by Gordon Jenkins that was one of Benny Goodman’s radio sign-off pieces, “Goodbye.” I previously knew this one from a mid-’70s Milt Jackson CTI release. It’s a lovely, lyrical piece and Pepper sets a stately, slow tempo that he maintains all the way through. The first time I listened closely to it, I noticed that after the first couple of choruses drummer Foster started to kick up the tempo but Pepper seemed to rein him in with the help particularly of Mraz. Reading the interview of Laurie Pepper by producer Zev Feldman in the generous and informative booklet, I found that she noted the same thing: “If it was a ballad, especially a really sad ballad, he wanted it slow,” she says. “And I don’t think Al even knew that coming in. … you can hear Al start to take it into a ‘New York ballad’, and then he just reins it back because Art does …” Pepper plays it mostly straight all the way except for a central section in which he employs avant garde-style tones.

From the first phrases of “Rhythm-a-ning,” it’s obvious that this isn’t the sweetly melodic Art Pepper. He still plays a strong melodic line when it’s called for, but his tone is forceful and aggressive. This combination of tunefulness and punchy tone are most apparent on Pepper’s composition “Make A List, Make A Wish.” It’s a piece very much of its time, with some soul jazz influence particularly in the piano and bass performances, and some fusion influence especially in Foster’s drumming. You think you’re not even going to hear a full sax solo until Pepper pulls one out near the end of this 18-minute tour-de-force. And the show concludes on an even stronger note if that’s possible, with the funky, almost rock ‘n’ roll “Red Car.” You can see what I mean here:

Art Pepper Live at Fat Tuesday’s is a treasure trove of music and history. It’s a sharp reminder that some great straight jazz was being played right through the 1970s and ’80s. In the right hands, like Art Pepper’s, the disparate threads of post-’60s jazz could be tied up together with solid straight-ahead into music that was thrilling and modern but still honored the music’s past.

Elemental/Widow’s Taste, 2015