Anyone who has seen any of the film versions of the Robin Hood legend has a good take on the story as presented by Tony Lee in Outlaw: The Legend of Robin Hood, although Lee has given us a prelude, of sorts, that introduces Robert of Loxley, son of the Earl of Huntington, in his childhood, as he and his father encounter an outlaw, his father’s old friend William Stutely, now known as Will of the Green, in Sherwood Forest. Will of the Green is captured by the Sheriff of Notthingham’s men, but the encounter leaves an indelible impression on Robin, particularly when Robin’s father kills Will as he is being hanged, the only mercy he can show his old friend.

Anyone who has seen any of the film versions of the Robin Hood legend has a good take on the story as presented by Tony Lee in Outlaw: The Legend of Robin Hood, although Lee has given us a prelude, of sorts, that introduces Robert of Loxley, son of the Earl of Huntington, in his childhood, as he and his father encounter an outlaw, his father’s old friend William Stutely, now known as Will of the Green, in Sherwood Forest. Will of the Green is captured by the Sheriff of Notthingham’s men, but the encounter leaves an indelible impression on Robin, particularly when Robin’s father kills Will as he is being hanged, the only mercy he can show his old friend.

Anyone telling a story as well-known as this one is facing some built-in constraints, not the least of which is that we know there’s a happy ending, and it’s to Lee’s credit that he makes the telling as absorbing as he does. He introduces some believable psychology, at least in the early portions, particularly in Robin’s relationship with his father, which went down the drain after the Will of the Green incident. It’s a sporadic insight, however, and not an important theme. What doesn’t seem to happen here is the kind of dramatic tension that keeps us moving along with the story. It’s a fluent and well-paced script, but not only are there no surprises, there’s not a lot of engagement. This is definitely a plot driven story, not character driven, which I generally find more engrossing.

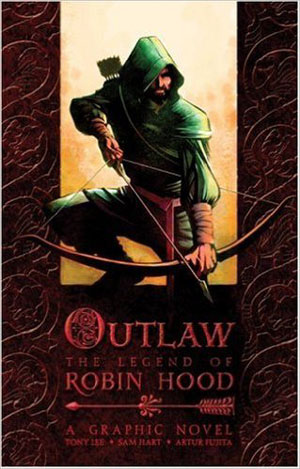

Sam Hart’s drawings and Artur Fujita’s color have to be taken as a unit. The character designs and general cast of the illustration are well done, rendered in a strong, muscular style with an active line — even figures at rest imply movement. The color follows closely, the whole book rendered in subdued tones that make good use of contrasts. The feel is of a woodblock print, especially in the craggy-featured faces (a characteristic which, somewhat unfortunately, Lady Marian shares).

There are a couple of quiet howlers: one spread shows wanted posters with Robin as the subject, with steadily increasing rewards offered. Another shows a group of peasants looking at an announcement for the fateful archery tournament that provides one of the climaxes to the story. Considering that this is twelfth-century England, I had to ask myself why anyone was bothering to post notices for people who couldn’t read them. (Granted, the peasants could have just been gawking, but still. . . .)

Visually, it’s a rewarding work, and the story, while not an edge-of-your-seat sort of thing by any means, does support itself. I can’t promise that I’ll be dipping into this one frequently, but it’s worth a look or two.

(Candlewick Press, 2009)