A few general remarks on Japanese comics first, for those who are new to this area. Manga is the term for Japanese comics in general, within which the two major divisions are shoujo, or “manga for girls,” and shounen, “manga for boys.” (There are other categories, including manga for men and manga for women.) The boundaries here are not hard and fast, and in my own experience refer as much to stylistic and thematic conventions as to demographics. Yaoi, generally used in the West to denote “boys’ love” or “BL” manga in general, falls pretty much within the shoujo conventions — and even within the demographic — with an emphasis on relationships and romance and a style that tends toward fluid, intuitive page layouts, a high degree of comfort and facility with abstract elements, and a visual flow that turns markedly away from the “frame follows frame” design most often found in shoujo — and Western comics, for that matter. This is not very rigid either — mangaka doing yaoi such as Makoto Tateno and Ayano Yamane routinely produce action/adventure stories, although they will play freely with page design.

A few general remarks on Japanese comics first, for those who are new to this area. Manga is the term for Japanese comics in general, within which the two major divisions are shoujo, or “manga for girls,” and shounen, “manga for boys.” (There are other categories, including manga for men and manga for women.) The boundaries here are not hard and fast, and in my own experience refer as much to stylistic and thematic conventions as to demographics. Yaoi, generally used in the West to denote “boys’ love” or “BL” manga in general, falls pretty much within the shoujo conventions — and even within the demographic — with an emphasis on relationships and romance and a style that tends toward fluid, intuitive page layouts, a high degree of comfort and facility with abstract elements, and a visual flow that turns markedly away from the “frame follows frame” design most often found in shoujo — and Western comics, for that matter. This is not very rigid either — mangaka doing yaoi such as Makoto Tateno and Ayano Yamane routinely produce action/adventure stories, although they will play freely with page design.

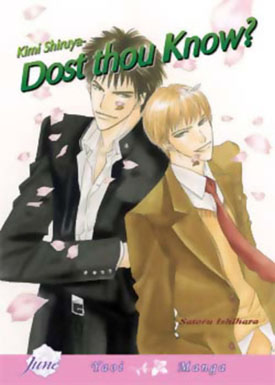

Now, about Kimi Shiruya:

Katsuomi Hanamori and Tsurugi Yaegashi are rivals in the sport of kendo, the Japanese art of the sword, competing in the high-school division; their younger brothers, Masaomi and Saya, compete in the junior-high division. As the story opens, Katsuomi has just defeated Tsurugi for the city high-school championship, while Masaomi was defeated by Saya for the junior-high trophy. When the Hanamoris get home, the expected celebratory sushi tray — their family are fishmongers — is packed up to be delivered for a house-warming — to the Yaegashis, who have just moved into the area’s high-rent district. On his way to deliver it, Katsuomi runs into Tsurugi, and they start talking: it seems that each finds the other rather a nicer fellow than he had expected, or really wanted — they are, after all, rivals.

There is a secondary story about the growing relationship between the younger brothers, Masaomi Hanamori and Saya Yaegashi, and of Saya’s crush on Katsuomi, which complicates things for everyone — mostly Masaomi.

Satoru Ishihara is an artist whose work has come to interest me a great deal. I think that interest is justified by what I’ve found in Kimi Shiruya: it’s a work of many levels, as much a product of reticence and implication as of overt portrayals, perhaps more so. There is a critical scene that happens not quite halfway through the story that illustrates Ishihara’s methods quite clearly — a kiss that we never actually see as it’s happening, although we see enough to know both Katsuomi and Tsurugi are willing participants, and that echoes throughout the rest of the story, both in dialogue and in graphics.

There are other dimensions here — this is not a straightforward romance. The story is built on a series of metaphors, starting with the central one: this courtship is a duel from the beginning. (This also says a great deal about relationships between men in general: we are created to compete, whether it’s innate or conditioned; the difference here is that the duel between Katsuomi and Tsurugi is conscious and deliberate.) The two young men are described over and over again in metaphors, as well. Katsuomi likens Tsurugi to the wind, elusive but able to deliver a telling blow, rushing through his defenses, while he admits that he himself is a “stampeding boar warrior,” all power and speed, direct and unstoppable. (As events demonstrate, however, Katsuomi is also patient and determined, while Tsurugi is stubborn to the point of being immovable.) And of course, there is the recurring motiv of the last two chapters from which the book takes its title: “Dost thou know my heart?” “Do thou knowest the tropic land within my heart?” A land of eternal summer, this land of the heart, which is when most of the story takes place.

A comment on that: that motiv takes place in the narration, which is usually by the point-of-view character, the third element, with dialogue and images, that, as in this story, both gives psychological insight into character and adds a dimension to the subtext, often lifting the whole complex to the realm of poetry. Ishihara uses it very effectively throughout.

A lot of this story happens “off-stage,” both a cause and an effect of that reticence I mentioned. Ishihara drops clues, which saves us from a series of “plot corrections” — if we pay attention, we know that something’s going on, and there are even one or two places where Ishihara lets us see it — but it’s only later we’re able to relate it to the main action. That raises the question of just how self-aware these characters are. By the end you know that both Katsuomi and Tsurugi knew where this was going from the beginning; it’s just been a matter of how much either of them was going to be able to shape the inevitable. (And looking at Katsuomi’s expression on the final page, you have to wonder, in spite of what’s just been said, who really won this duel.) The same holds true of the younger brothers: both are aware of what’s going on with their older sibs, and Masaomi, as we are shown in one brilliantly placed frame, fully realizes the similarities to his own situation, but we’re not sure how much Saya understands that he’s following Tsurugi’s pattern.

Ishihara notes that Kimi Shiruya took three years to complete; the story itself covers two years, perhaps a bit more. Yes, there is a change in the graphic style: by the last two chapters, the art is both freer and more definite, more sure of itself. There are changes in character renderings that can at least in part be attributed to the passage of time in the story, especially with Masaomi and Saya: there’s a lot going on between the ages of twelve and almost fifteen. And some of these later images are simply beautiful. There’s a sequence toward the end of Katsuomi eating a tomato fresh from the vine that itself is worth the price of the book: it moves back and forth from humor to introspection to pure sensuality, all gorgeously drawn, and built around another metaphor that leads right to the core of the story: the sweetness of fruit allowed to ripen in its own time.

I’ve barely scratched the surface here. There are subtle ways in which the secondary story of Masaomi and Saya intersects the main story and then returns to its own, nearly parallel path. There is the innuendo that fuels the eroticism of what is possibly the most truly erotic yaoi I’ve read to date — and this, mind you, without the almost obligatory sex scene — which is nothing compared to Tsurugi’s enigmatic expressions. There are the mood shifts that echo changes in the relationships and that infuse the entire presentation, both dialogue and images. And more.

Ishihara has made full use of the potential of the graphic novel medium in this one. Kimi Shiruya is to my mind not only a superb example of yaoi, but a remarkable example of graphic literature in any genre.

(Digital Manga Publishing, 2005 [orig. Shinshokan Co. Ltd (Japan)., 2003])