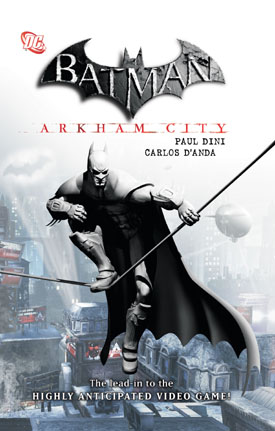

Splashed across the bottom of the dust jacket to Arkham City is “The lead-in to the highly anticipated video game!” Let that be a warning.

Splashed across the bottom of the dust jacket to Arkham City is “The lead-in to the highly anticipated video game!” Let that be a warning.

Batman and the Joker got into it in a big way a year ago, with the result that Arkham Asylum was destroyed and Gotham’s worst criminal psychopaths are running around loose. Quincy Sharp, who is not the first person to ride into office on the coattails of disaster, is now mayor, and one of his first acts is to set aside a part of the city for the those very criminal elements. There will be walls and barricades, and on their side, the former inmates will be free to build their own society. As part of this program, all costumed vigilantes are now outlaws. (Martial law will come later, along with the Mayor’s elite Tyger guards.) It doesn’t take Batman long to figure out that Mayor Sharp is someone’s puppet, but it takes a while longer to figure out who that someone is. And in the meantime, all the baddies are making their way to Arkham City, with the Joker (who is dying from the effects of the Titan drug) and the Penguin facing a confrontation to see who will be kingpin.

There’s not a lot to say about this installment in the ever-growing, multifaceted Batman franchise. It’s a set-up — the only thing that really happens here is that we learn who’s pulling the strings. The rest of the story is a series of set-pieces, all violent, which do nothing more than lead to a blatant hint that there will be a continuation of one sort of another. There are also a series of “digital chapters” that make up about the last third, more or less crammed together with no transitions (and no individual title pages), encompassing a variety of drawing styles, all summarized on an overall title page that leads off the section.

The graphic style for the real “story,” from Carlos D’Anda, can best be described as “Neon Grotesque.” Like the story itself, it’s somewhat over the top, although given the way steroid-conditioned bodies have influenced character designs in superhero comics over the past couple of decades, maybe it’s not so extreme as all that — at least, within the genre. This goes far enough that one of the Trask siblings — either Terry or Tracy, and isn’t interesting that the names are gender-neutral? — so much resembles her brother that without the difference in costuming, it would be hard to tell them apart. Rest assured, though — the other female villains are voluptuous enough for the most hormonally supercharged teenager. Batman himself is a craggy hunk whose only facial expression is a scowl, and I have to admit I’m not sure about Robin’s depiction here — it calls to mind nothing so much as a used-up prize fighter, which doesn’t really fit the idea of “Robin” all that well. (At least, not for us traditionalists.)

You may have gotten the idea that I’m not terribly impressed with this title. You’d be right. I won’t go so far as to say it’s an example of shameless marketing, but it certainly doesn’t have the substance to stand on its own. I admit to being influenced by examples of American comics and Japanese manga in which writers and artists have portrayed psychological depth with a fair amount of subtlety and created a synergy among the elements that establishes “graphic novel” as a true form, and this just doesn’t measure up.

(DC Comics, 2011) Originally published as Batman Arkham City 1-5 and online as Batman Arkham City Digital Chapters 1-5.