This review was written by Rebecca Scott.

I admit to some trepidation about writing this review. So many authors, editors, musicians, and reviewers have said so much about these books. This series altered the face of the comics industry. It’s drawn in thousands of people who had never read a comic book before.

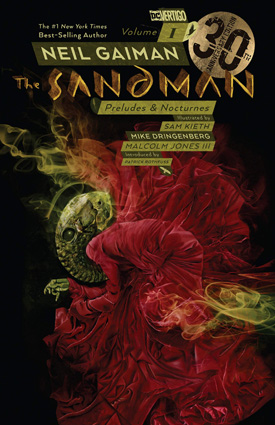

Preludes and Nocturnes

In June of 1916, in Wych Cross, England, the Order of Ancient Mysteries attempts to summon Death and bind him. The spell summons something, a paper-white and rake-thin man, robed in black, helmed with the skull of a dead god, bearing a sack of sand and a ruby. This is not Death. This is Death’s younger brother, the Sandman, the Oneiromancer, the Prince of Stories, His Darkness Lord Dream of the Endless. Trapped and incapacitated, he can do nothing to stop the Order from stealing the helm, the ruby, the sack. For over seventy years, he will remain imprisoned. Around him, as he lies trapped in magic circle and glass bubble, the world changes. And, with his imprisonment, a strange illness spreads. All over the world, people fall asleep and will not wake, or walk in a strange half-dream.

In June of 1916, in Wych Cross, England, the Order of Ancient Mysteries attempts to summon Death and bind him. The spell summons something, a paper-white and rake-thin man, robed in black, helmed with the skull of a dead god, bearing a sack of sand and a ruby. This is not Death. This is Death’s younger brother, the Sandman, the Oneiromancer, the Prince of Stories, His Darkness Lord Dream of the Endless. Trapped and incapacitated, he can do nothing to stop the Order from stealing the helm, the ruby, the sack. For over seventy years, he will remain imprisoned. Around him, as he lies trapped in magic circle and glass bubble, the world changes. And, with his imprisonment, a strange illness spreads. All over the world, people fall asleep and will not wake, or walk in a strange half-dream.

It is not until 1988 that he finally escapes and begins to take vengeance. He is weak, though, and must return to his own realm, called the Dreaming. There he is helped by some of those who have remained in the kingdom even as it decayed due to its master’s absence. To recover his tools, long missing from the stores of the Order, he must go on a quest, and a quest requires an Oracle. To that end, he summons the Triple Goddess of many names. He asks three questions and is given three answers.

First he travels to London, to ask a smartass magician named John Constantine where he might find the little bag of sand John bought at a garage sale.

Next, he ventures into Hell itself to challenge the demon Choronzon for possession of his own helmet. They play the oldest game, and then Dream must face down Lucifer Himself and all the hordes of Hell to escape.

Difficult as those encounters were, the worst is yet to come. He must do battle with a madman intent on destroying the world, and his very existence is on the line.

Finally, having completed every task and surmounted every obstacle, Dream … goes to feed the pigeons in the park. There, he meets his sibling, the one that the Order of Ancient Mysteries set out to trap in the first place: Death. And Death, we find, is a perky little goth girl, who quotes Mary Poppins, says “peachy keen,” calls her brother an idiot, and throws bread at him. Then she takes him on her round of duties, as she collects the souls of the newly dead. As he comes to appreciate what his sister does, he is comforted. He fills his heart with the sound of her wings.

The Sandman is a story about stories. Morpheus, the King of Dreams, is its protagonist. He is the anthropomorphic personification of Dream and Story. So what else could this be but a story about stories?

Preludes and Nocturnes follows a linear story line, something perhaps half of the volumes of Sandman do. It’s a good thing, too, or else we’d be thoroughly lost from the beginning. This is the introduction to the universe and some of the key cast members, and to Morpheus himself. It’s also the eight issues that Gaiman used to figure out what he was doing with the series.

This isn’t Gaiman’s first comic (Violent Cases and Black Orchid, both with Dave McKean as artist, came before it), but it is his first monthly, and it’s still very early in his comics career. And it shows.

Each of the eight issues of Preludes and Nocturnes has a different style, feel, and even genre (or at least sub-genre). Sandman started out as a horror comic, and most of the stylistic choices reflect that (barring Issue 8, “The Sound of Her Wings”), but he echoes classic English horror, 1970s horror comics, gritty urban British horror, 1940s John W. Campbell, and the darker side of the standard DC Comics heroes and villains before beginning to find his own style of horror in Issue 6, “24 Hours.” The style-hopping works well, in an odd way, partially because each issue is a discreet story as well as being a chapter in the larger story arc of the book (which is, of course, only one chapter in the story of the Sandman). Also, each style is chosen well for the story. It’s hard to imagine, say, John Constantine (a Sam Kieth creation originally) without that touch of modern griminess.

Then, too, the changing styles and settings show us different facets in Dream’s personality. These first looks at Dream’s inner workings become more and more important to keep in mind as one gets farther into the series, and will ultimately provide some of the insights necessary to understand the end of this two thousand (or so) page epic, an end Gaiman had in mind from the beginning.

Most of the characters to be found in these pages are vibrant and well-rounded, even those with small parts. We understand Burgess, head of the Order that imprisons Morpheus, and his driving ambitions. We like seedy Constantine, and can feel his pain. We feel Judy’s desperation, Bette’s inspiration, and Mark’s aspirations. Even Lucifer, Prince of the Damned, shows a very human anger at having been bested. But we do not understand Dream. Not really.

Dream is a subtle character, some have said a weak character. Perhaps that’s even true (you’ll have to judge that for yourself). But then, perhaps that’s part of the point. The Endless, Gaiman says in The Sandman Companion, aren’t causative, and are barely reactive. They are personifications of concepts. And in part, The Sandman is the story of how Dream learns to react, and to cause. But always very subtly.

The art is mostly wonderful: shadows, colors, distortions, and layouts only heighten the stories’ impact. Sam Keith as penciler and Mike Dringenberg as inker, with Robbie Busch as colorist, create a moody first three issues. When Keith leaves, Dringenberg becomes penciler and brings in Malcolm Jones III as inker, and a kind of clarity of form takes over, which actually begins to suit the story better. Todd Klein as letterer gives each voice a resonance. You can hear the darkly echoing quality of Dream’s voice, like Christopher Lee doing Terry Pratchett’s Death. Lucifer’s high, clear voice rings sharp and cold and formal. Doctor Destiny’s broken mind is echoed in the jagged letters, like a constantly cracking voice.

A few failures, visually: the body turned inside out and splattered across a room is just sort of gooey and brown; the awkward stresses in Morpheus’ upper- and lower-case speech in the first few issues; perhaps one or two others, nothing very significant.

My personal favorites in this volume are “24 Hours” (#6) and “The Sound of Her Wings” (#8).

The Sandman was conceived and listed as a horror comic, but personally, I’ve only ever considered the first two volumes to be horror. The rest just doesn’t scare me. Preludes and Nocturnes and The Doll’s House are pretty creepy, and of all sixteen issues collected in these two volumes, “24 Hours” is the one that scares me most. Imagine twenty-four hours in a diner with a madman who can control your dreams… This one still gives me chills every time I read it.

“The Sound of Her Wings” is widely acknowledged as a turning point in the series, the place where Gaiman really found his own voice. It’s also a longtime fan favorite. The story is simple, quiet. Dream follows his sister Death on her rounds, and he heals. Death attends the passing of an old Jewish fiddle player, a struggling standup comedienne, an infant in a crib. Her tenderness and humor with each of them as she enfolds them in the wings we never see will make you smile or cry or both. And there is a poem, which begins:

“Death is before me today:

Like the recovery of a sick man

Like going forth into a garden after a sickness.”

It’s a Babylonian poem Gaiman took from Joseph Campbell’s Masks of God.

The Doll’s House

A plot summary of The Doll’s House is almost impossible, but here’s an attempt:

The Doll’s House opens with an African rite of manhood that involves a folk tale. These people were the first people, and once, in this place, they had a great city built of glass. Their Queen, Nada, had no man, and refused many. One night, she saw a man stand at the foot of her tower, and she loved him; he was Kai’ckul, the Lord of Dreams. But it is not given to mortals to love the Endless. She fled him, fearing repercussions, and took her own maidenhead. He did not care, and so they spent a night making love. In the morning, the Sun saw them, and destroyed her city. In terror of what she had done, and what had happened, and what might yet happen, she killed herself. Kai’ckul followed her into the Sunless Lands, and there he proposed to her, and said that if she refused, he would condemn her to hell. What could she do, but refuse? (And we know that she did, because Dream saw her, imprisoned in Hell, when he journeyed there for his helm, and he would not release her.)

Now, abruptly, we meet two of Dream’s younger siblings: Desire, a creature whose gender and sex shift constantly, gorgeous and self-centered as Desire always is; and his/her twin, Despair, who rips her face with her barbed ring. They plot against their brother.

Rose Walker and her mother Miranda travel to England, brought there from America by a mysterious benefactor. Rose dreams of a census of dreams, and learns that four are missing (Brute, Glob, Fiddler’s Green, and the Corinthian). She learns also that she is a vortex, an annulet… but not what that means. The Walkers meet Unity Kincaid, one of those who slept while Dream was imprisoned. Unity bore a child during her sleep, and that child was Miranda.

Supported by Unity’s vast resources, Rose goes to Florida to seek her little brother, who has been lost to her since her parents’ divorce seven years ago. In Cocoa, she rents a room in a house with a number of odd residents, and a drag queen for a landlady. She worries about her brother, Jed.

Jed dreams of flying, of being loved, and wakes to a reality in which he is imprisoned in a rat-infested basement, and beaten when he emerges. Nestled in Jed’s dreams are Brute and Glob, two of the four missing dream-creatures; and Hector and Hippolyta Hall, a dead man and his pregnant wife. Dream discovers that Jed’s mind has been sealed off from the Dreaming.

When Rose, now apprised of her brother’s whereabouts, sets out to find him, Gilbert (one of her housemates) goes along. Somewhere in Georgia, their car breaks down. Exhausted, they take shelter for the night in a hotel that has been booked for a “Cereal Convention,” whatever that might be.

Dream removes the four intruders from Jed’s mind. Three of them he sends to their appropriate places. Lyta, though, he sets free, through he tells her that the child she bears is his. And then he leaves for a prior appointment.

Towards the end of the fourteenth century, Dream and his sister Death go together to a tavern in England. There, they hear a man named Robert (or Hob) Gadling say that he intends never to die. With a smile, Death decides to grant him that. Dream tells Hob that, if he is not dead, they ought to meet again at the tavern, a hundred years hence. Every hundred years thereafter, they meet and discuss how the world has gone. Up or down, Hob always wants to live. And, during the sixteenth century, Dream strikes a bargain with an aspiring playwright, one Will Shaxberd. Dream and Hob become friends through the ages, and it is to the club that stands on the site of the White Horse Tavern that Morpheus goes when he leaves Lyta Hall.

In Georgia, men and women who speak in metaphors of death gather at the Cereal Convention. The Corinthian, a young and handsome man with a shock of white hair and dark sunglasses, comes as the guest of honor. We realize, slowly, the truth about this convention.

As the dust settles, Gilbert finds Jed, comatose and dehydrated, in the trunk of a car, and he and Rose rush him to a hospital. As Rose waits for news of him, for news of Unity who has had a stroke, she and her housemates begin to dream … and she learns at last what it means to be a vortex of Dream.

It’s worth noting that the first editions of The Doll’s House also contained “The Sound of Her Wings.” This was a marketing decision, not an artistic one, which is why I won’t bother covering that material twice.

This is a story about women, and about how men see women. It explores Maiden-Mother-Crone imagery, the process of a woman taking on the responsibilities of adulthood, male-to-female transgender and transsexualism, misogyny in its vilest and most extreme form, the image of a woman as a vessel, and the power of a woman to remove walls. And in nearly every issue, there is the image of a heart. Most resonantly, there is the image of a heart being handed from grandchild to grandparent, twice.

Symbolism, reference, and homage are thick and multilayered here. The title refers to both the play (by Henrik Ibsen) and the children’s book (by Rumer Godden). Jed’s dreams are a pastiche of the early 20th century comic Little Nemo in Slumberland, and contain the 1970s Sandman character. An old, primal version of the Red Riding Hood story plays itself out, in telling and in life. Minor characters from other comics series are resurrected (quite literally).

And you can miss nearly all of it, and still enjoy yourself. I did, eight or nine years ago, in high school. The more I learn, and the more I reread the series, the more I understand and enjoy it. Isn’t that one definition of literature? That the educated can read it with enjoyment, and reread it with more?

Dringenberg and Jones bring it all to life, the grotesque and the gorgeous, with affecting illustrations and occasionally brilliant layouts.

Nada’s story, “Tales in the Sand” (#9); Hob’s, “Men of Good Fortune” (#13); and “Collectors” (#14) all shine, each in its own way. In “Tales,” Gaiman creates out of thin air an authentic-feeling folk tale, with true-to-form language, rhythm, and decay. “Men of Good Fortune” involved a huge amount of historical research, and aptly demonstrates both the changes that take place over time, and the constants of human attitude. It also sets the stage for several future stories. And “Collectors” is chilling from beginning to end, its biting winds seeming to blow right through your soul.

Dream Country

After The Doll’s House and before Season of Mists, Gaiman wrote four single-issue stories, exploring ideas he’d had during the longer story arcs. These four issues (plus the script for one of them) make up Dream Country.

Dream Country is introduced by Steve Ericson, who talks about dreams that aren’t dreams.

“Calliope” is the first story, illustrated by Kelley Jones and Malcolm Jones III. Calliope, whose name means “beautiful voice,” is the youngest of the nine Muses of the Greeks. A writer trapped her with rituals, imprisoned her in a tower and used her for inspiration. Now that writer is very old, and he sells her to a young novelist. He, too, imprisons and uses her, for years. Her only hope for escape is her former lover, the father of her child (“That boy-child who went to Hades for his lady-love, and died in Thrace, torn apart by the Sisters of the Frenzy, for his sacrilege.”) … Dream of the Endless.

“Calliope” reads like Gaiman’s darkly amused, slightly exasperated answer to the perennial question, “Where do you get your ideas?” Every writer gets this question regularly, and most of them eventually develop stock answers to it.

But “Calliope” is also a serious story, about obsession, and how one justifies things to oneself, and what one will give up to have one’s wishes granted.

“A Dream of a Thousand Cats” (which my kitten Delight wants to eat) allows one Siamese to tell the story of her encounter with the Cat of Dreams (a huge night-black tom with eyes that shine red), who told her that once the Earth was ruled by giant cats. But a thousand humans dreamed, together, of a world ruled by humans, and the next day, it had always been ruled by humans. Now the Siamese travels, and tells her story, and tries to get a thousand cats to dream together…

This story reminds us that Dream is not only the master of human dreams, but of everything that dreams. He is only anthropomorphic in human settings. That is not his true shape. “Thousand Cats” reminds us too of the power of dreams, and how they can shape reality.

Also illustrated by the unrelated Joneses (Malcolm and Kelley), the art in this issue is organic and graceful, and very feline.

In “Men of Good Fortune” from The Doll’s House, we saw the Sandman, at one of his meetings with Hob Gadling, notice a young man who wanted to be a great playwright. And Morpheus struck a deal with him. This story shows us the first half of Will Shakespeare’s end of that bargain.

Shakespeare, his son Hamnet, and Lord Strange’s Men travel to the South Downs, to put on Will’s new play, “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” But today, they will not play at an inn, and their audience will not be human. This is the first of two plays commissioned by Morpheus, which are to celebrate dreams, and he has invited those the play is about, and for. Titania, Auberon, and all their Court come to sit on the greensward and watch a story which never happened, but which is true nonetheless. And by the end of the play, the lines between actor and audience, story and reality, will have blurred considerably.

Having done a paper on Shakespeare some years ago, I was aware that Shakespeare’s only son died young, and was named Hamnet (yes, it’s a variant of the name Hamlet). But it never occurred to me how little Hamnet would have seen of his father, nor how Shakespeare’s passion for his craft would have alienated them. It occurred to Gaiman, though, and he made that the human center of this story. There is, of course, a lot more going on, but William’s relationship with his son shows the true price he has paid for his inspirations.

Gaiman put a huge amount of research into this issue (though he admits to two anachronisms, and blames one on Dream and the other on the peculiar chronology of fairy folk). So did Charles Vess, the illustrator. The artwork is simply beautiful.

“Facade” rounds out our little sojourn through the dream country. Urania Blackwell was granted superpowers in a tomb in Egypt, and became Element Girl, sidekick to Metamorpho. Now she feels that she is nothing more than a freak, and lives her life enclosed in her tiny apartment, living for the one phone call a week she gets to make to the man who arranges her monthly “disability” check. She can shape her body into any substance that exists, and all she wants to do is die. How does someone who has no blood, who simply metabolizes poisons, who cannot be damaged by a bullet, kill herself?

Perhaps Death will know.

Children, teenagers, and adults have thrilled to superhero stories for decades now. Most of us have dreamed of being Superman, or Wonder Woman, or Buffy, or whomever. Wouldn’t it be wonderful, to have those powers, to be able to do, well, anything? And “Facade” answers, “No. Not necessarily.”

What happens to someone who becomes so different from her fellow humans that she cannot live among them any more?

Colleen Doran and Malcolm Jones III’s art makes Rainie far more human than she can believe she is.

Gaiman’s script for “Calliope” is included in this volume, partly because Gaiman wished that such a thing had been published when he first got started in comics, and partially just to indulge the fans’ curiosity about the process. If you’re the sort who wants to go backstage after Phantom, who asks the magician how it’s done, who watches “The Making of….” documentaries, you may enjoy this script. The comparison between Gaiman’s ideas and intentions and Jones’ execution is interesting, as are the various notations by the collaborators. If you’re not that sort, you won’t miss anything by skipping it. (I failed to read the script for years, and didn’t mind, then read it for this review, and thoroughly enjoyed it.)

Fables and Reflections

This volume of single-issue stories was published in between Volume 3 (also single-issue stories) and 4 of the series.

The title of this collection refers to the two series of single-issue stories it contains. The first is Distant Mirrors, issues 29, 30, 31, and 50. These four issues are about emperors, rulers, kings … historical ones, with accurate details. Emperor Norton I of the United States of America (“Three Septembers and a January,” #31); Maxmilien Robespierre, the most powerful man in revolutionary France (“Thermidor,” #29); Imperator Augustus Caesar, first Emperor of Rome (“August,” #30); and Haroun al Raschid, Caliph of Baghdad (“Ramadan,” #50) each have something to teach us about our own day and age. The second group of stories is Convergence, three stories in which very diverse characters come together, and tell stories. These three are “The Hunt” (#38), “Soft Places (#39), and “The Parliament of Rooks” (#40). This volume also includes “The Song of Orpheus,” which was The Sandman Special #1; and “Fear of Falling,” which appeared in Vertigo Preview #1.

The volume opens with the ten-page mini comic “Fear of Falling,” illustrated by Kent Williams. In it, a young playwright is about to cancel the production of his first play one week before opening night. Why? Because he’s afraid of falling … as afraid of success as of failure. He falls asleep while watching Hitchcock’s Vertigo (a joke, as this short was published in the preview comic that launched DC’s Vertigo line of fantasy/horror comics for adults, with The Sandman as its flagship), and has a dream. Despite his fear of heights, he climbs a tall promontory, at the top of which is the Sandman. Dream tells him that, when you fall in dreams, sometimes you wake, and sometimes you die, but that there is a third option.

Gene Wolfe provides us with a social introduction to these stories. “This is Pythia. She lives in a cave — it’s haunted by the ghost of a giant snake and she answers questions in cryptic verse. Her answers are always true, and generally a little truer than we like.”

Shawn McManus drew “Three Septembers and a January,” the story about the first and only Emperor of America. (Yes, the title is a tip of the hat to Four Weddings and a Funeral, which was a good trick, as the comic came out three years before the movie.) If you’ve never heard of Joshua Abraham Norton, then you’re in for a treat. Somewhere a little past the middle of the nineteenth century, an Englishman from Africa lost the fortune he’d made in San Francisco. Financially, he was ruined. Emotionally and intellectually … well, he declared himself Emperor of the United States. Though no one followed his proclamations, the newspapers printed them, the city gave him his suit of state, and the shops and eateries accepted his currency. When he died, he was given a funeral with full Masonic rites, a large monument (still a tourist site today), and a funeral procession over two miles long. Later, one of the more peculiar postmodern neopaganisms venerated him. And Neil Gaiman wrote a story in which he became the playing ground, and the prize, in a contest between Dream and his three youngest siblings.

In “Thermidor” (brought to us by the pencil of Stan Woch and the pen of Dick Giordano), we meet for the first time Dream’s son, or what’s left of him. Johanna Constantine is hired by the Sandman to travel into revolutionary France to retrieve the immortal severed head of Orpheus. This is the time of the Reign of Terror under Maxmilien Robespierre, who wants to destroy both the head and the headhunter. But Orpheus is a singer out of myth, and his song wakes echoes in the mind and the heart.

“Thermidor” illustrates the danger of the demagogue, the lengths to which people will go in the name of “the people” or “the nation.” Like the other Distant Mirrors issues, this story has an ever-increasing (and scary) relevance for people today, particularly Americans. The title, by the way, refers not to a lobster dish, but to a midsummer month on France’s revolutionary calendar. The astute may have already noticed that all four titles in this set refer to months.

“The Hunt,” with Duncan Eagleson and Vince Locke’s artwork, is the first of the three Convergence stories. In a 1980s living room, a grandfather tells his too-hip early-teen granddaughter a story of “the old country.” Young Vassily lives with his father deep in the forest until the day the gift of a gypsy peddler sends him on a search for his dream. Along the way, he encounters an extremely tall and thin librarian who wishes to purchase the book in Vassily’s pack. Vassily will sell it to him only in return for his heart’s desire: the duke’s daughter, pictured in the miniature portrait that the gypsy gave him. His other encounters include a murderous innkeeper, Baba Yaga, a number of his own people, and the librarian’s master (a tall pale man in black, of course).

Gaiman says, “If ‘The Hunt’ works, it will do that nice thing of having you get to the end and then want to start again at the beginning.” It works. I still read it twice.

We have Bryan Talbot and Stan Woch to thank for the moving shadows and light in “August,” in which Caius Julius Caesar Octavianus, the Emperor Augustus, spends a day as a beggar, so that he may think without the gods of Rome watching him. He thinks of prophecies, and of boundaries. This story just might explain why the Emperors of Rome turned out as they did. It might also serve as a cautionary tale for the politicians of today.

“Soft Places” is given its necessarily dreamlike quality by John Watkiss, as a young Marco Polo, crossing the Desert of Lop, falls into the soft places on the edges of the Dreaming. There he and the odd companions he meets tell stories. A charming tale, in which one hears Gilbert mention Dream’s new lady-love.

“Orpheus,” with Bryan Talbot and Mark Buckingham providing art, is a nearly straight retelling of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, except that here, Dream is Orpheus’ father (and not a Thracian prince), and it is Death’s intervention that permits him to travel safely to the Underworld. If you don’t know the myth, then I won’t spoil it any further. But I know the myth, and have always liked this version.

In “Parliament of Rooks,” elucidated by the illustrations of Jill Thompson and Vince Locke, Daniel Hall dreams his way to the House of Secrets, meeting Abel (whose home it is), his brother Cain, Eve the Raven Woman, and Matthew (her raven). Three old storytellers and an audience…. Well, what did you think they’d do? Play Parcheesi?

Finally, we come to “Ramadan.” This issue instantly became a favorite among readers. P. Craig Russell’s incredible imagery brings the entire tale closer to one of Scherherazade’s than even its content could make it. During Ramadan, month of fasting, the Caliph of Baghdad, Haroun al Raschid, looks upon his city of wonders, and knows that it is at its height. He knows, too, that any civilization which has reaches its height must fall, and he worries that it will then be forgotten. And so he calls on another monarch, the Prince of Stories, and they walk in the soukh, the marketplace, and discuss a deal. In the end, we find that this was a tale told to a small, crippled boy, by a beggar, in the bombed-out Baghdad of today.

Volumes 4, 5 & 6

These three volumes are quest stories. Some of the scenes (Breschau’s punishments, Charles Rowland’s school holidays, any scene with George in it, the Corinthian and the Oran Oatan) are creepy in one way or another, yes. It’s Neil Gaiman, you’re not going to escape that. But it’s not what these stories are about. Dream quests to make amends, and to rid himself of unwanted property. Barbie quests after the salvation of a land she has forgotten. Delirium quests to find her lost, beloved brother.

What do you you quest after, in Dream’s Realm?

Season of Mists

“To absent friends, lost loves, old gods, and the season of mists; and may each and every one of us always give the devils his due.”

–Hob Gadling’s toast

When his sister Death shames him with it, Dream finally admits that he was wrong to condemn Nada to Hell, ten thousand years ago, for refusing to be his queen. Having owned up, the only thing he can do is to go and release her and tell her that she is forgiven. There’s only one problem: Lucifer has sworn to destroy Morpheus for embarrassing him before all the Hordes of Hell. Nonetheless, to Hell Morpheus will go.

But when he gets there, he find the Hell of Lucifer empty, and its resigning master locking the last gates. Rather than fight him, Lucifer gives Dream a gift, the Key to Hell. Dream doesn’t want it… but everyone else does.

Gaiman began planning this story when he was writing issue 4, which depicted the Sandman going to Hell to retrieve his Helm, lost these many years and in the posession of a demon. On that fateful visit to Hell, Morpheus sees Nada, his old love, whom he still loves but has never forgiven. At the time, we got no further story on her. Five months later, we got her backstory, in “Tales in the Sand.” Nada had been an African queen who had refused Dream because it was not given to mortals to love the Endless. Having watched her city destroyed, she died rather than bring more danger upon the people. Having died, she let Dream sentence her to Hell, until he should stand before her and tell her that she was forgiven, rather than be his Queen of Dreams.

And, a year after that, we finally found out what happened next.

This collection is a feast for lovers of mythology, even those who (like me) are sticklers for accuracy. Odin cannot think or remember without Huginn and Muninn, the ravens Thought and Memory. Thor is redheaded and bearded. Loki is handsome despite the scars around his mouth. Egyptian, Japanese, and Judeo-Christian figures are similarly well depicted. And the representatives of Queen Titania are simply charming.

Season of Mists also introduces us to two more members of Dream’s family, and introduces us more thoroughly to the members of whom we are already aware. Destiny and Delirium are the oldest and youngest of the Endless; Destiny is a tall figure in a grey robe, chained to a book; his youngest sister (who used to be called Delight) is a childlike waif with mad-colored hair and odd-colored eyes. The brief essays describing each of the Endless are both lovely and enlightening.

But, we become aware, there is one of the Endless to whom we have not been introduced, and whose name has not yet been revealed. Nor is it here: he is known only as “the prodigal.”

In previous stories, Dream has shown a very limited range of emotions. Now, we see that range expanded. He is shocked, touched, wistful, worried, and dumbstruck. It’s a measure of how much he has changed, and is changing, that we see so much when he’s under stress. He dons again his obdurate mask, as soon as he can, but we can see a little tenderness gleaming through the cracks in his armor.

Hell, in the world of The Sandman, is not a place where a vengeful deity sends those who have offended Him. Instead, it is a place where dead mortals choose to go (presumably without realizing that the choice is theirs) if they believe that they have sinned. It is, perhaps, also less of a place than a state of mind.

If Hell is not what we expect, then what is Lucifer? He is neither the Root of All Evil (“‘The Devil made me do it.’ I have never made one of them do anything. Never,” he protests), nor soul-monger (“How can anyone own a soul?” he asks). Instead, he is disillusioned and world-weary, and ready to try something new. He is cruel enough to giggle at what he’s putting Dream through, and kind enough to compliment the Daughter of Lilith who loves him. He is embittered at the realization that even his great rebellion is part of his Creator’s plan, but not so much that he cannot appreciate a sunset as His work.

The artwork… I can only praise Mike Dringenberg and Malcolm Jones III so many times. Their styles and Gaiman’s are well-suited. But this volume also features a number of other artists. Kelley Jones’ gods and demons, and especially his Lucifer, are wonderful. Matt Wagner’s returned dead are disgusting, charming, or horrifying, exactly when and how they ought to be. My only complaint on the artwork is that the shadows are sometimes too thick and black, losing some expression and character.

Episode four of this story follows Gaiman’s tradition of inserting a seemingly separate story which serves to point up the central themes of the greater story. Edwin Paine and Charles Rowland, a dead boy and a dying boy, show us that we don’t have to stay anywhere forever.

Harlan Ellison introduces this volume with a pointed essay on perfection and excellence.

A Game of You

Once upon a time, Barbie lived in Florida, with her husband Ken. Then, one night, her housemate Rose Walker discovered what it meant to be a Vortex of Dream, and Barbie lost some things. She lost her husband, her meaning, and her dreams. One she is well rid of, one she is searching for, and the last has come searching for her. Because, when she dreamt, Barbie became Princess Barbara, the Saviour of the Land, who protected it from the Cuckoo. Now Barbie finds her old dreams impinging on her new life, and the only way out is to complete the quest she started when it was “only a dream.”

Once Barbie was one of the weird housemates of Rose. Now she has a cast of weird housemates herself, including the lesbian couple upstairs (one of whom is haunted by what was, and the other by what may be), the several-thousand-year-old witch, the preoperative male-to-female transsexual, and the minion of her dream-adversary.

The Sandman intentionally alternated between masculine stories and feminine stories, and between stories comfortable for comics readers and ones that made them uncomfortable. A Game of You is generally considered to be the most uncomfortable story in the Sandman library, and certainly it explores the concepts of femininity and femaleness in a way no other Sandman story does. But the reason it’s so uncomfortable for so many fans is probably that it explores the concept of identity.

“Identity blurs on the Moon’s Road… In the pale light of the Moon, I play the Game of You. Whoever I am. Whoever you are. All sense of where I am, who I am, and where I’m going, has been swallowed by the dark. And I walk through the stars and sky… a trinity of dreams beneath the moon.”

Names are important here: names that are the same, names that are different, names that are not. Can you change your identity by changing your name, by playing the game of you?

Nobody who hasn’t played that game will find it comfortable; neither will some who have played it. Comfortable, no. Fascinating, yes.

A Game of You alternates between levels of reality, and uses repeating motifs to make the real world seem more surreal and the dream world more prosaic. The points where the two worlds meet seem almost normal.

The best and most fascinating parts of this volume are in the details, really. Puns, reflections, references, and subtleties are the order of the day. All of The Sandman rewards a deep, close reading, but perhaps A Game of You more so than any of the other volumes.

Shawn McManus is good at drawing horror. So are lots of people. Shawn McManus is good at drawing fantasy. So are lots of people. What McManus can do that makes him invaluable to this story is draw them both, side by side, and have them mesh perfectly. Colleen Doran adds a woman’s touch to the illustration of the single issue most concerned with gender, giving an edginess to the transformation of the other women’s worlds.

A Game of You introduces two of my favorite Sandman characters, Thessaly and Wanda. Thessaly shows us why the Greeks feared witches, and yet she herself is an amazingly down-to-earth and together woman. She seems, as Hazel puts it, “so vanilla.” Wanda is exactly the opposite of vanilla, brash and proud and very sure that’s she’s woman (however frightened she might be of that surgery). She keeps her humor in the face of things that scare her shitless, and all she wants is to protect her friend. She’s the only one acting unselfishly.

I feel I ought, briefly, to touch on the controversy surrounding Wanda. A lot of readers have assumed that Gaiman shares the opinion of the Moon Goddess and Thessaly, or that he feels that Wanda is not certain of her own identity. Much to the contrary, Gaiman has stated that he sides with Wanda.

Samuel R. Delaney provides this volume with an opening commentary on the language and art of A Game of You. It’s worth reading, but only after you’ve finished the story. It won’t do you much good before.

Brief Lives

Three hundred years ago, Destruction, the middle sibling of the seven Endless, abandoned his realm.

Now Delirium tries to convince her brothers and sisters to go with her, to search for their missing, and missed, brother. Working her way up from her next-eldest siblings, she gets to Dream before finding someone who will help her.

Dream is suffering from a broken heart, or thinks he is. For weeks now, he has stood in the rain, mourning the loss of an unnamed lover. He agrees to accompany Delirium, not to look for Destruction, but to look for her.

As they search, looking first for those friends of Destruction who will not be dead, people begin to have terrible mishaps and begin to die.

In the end, Delirium and Dream find their brother, but not without cost. Rare indeed is the individual who can seek Destruction and return unscathed. Dream is not such a one.

The prevalent themes in Brief Lives are immortality (or the illusion thereof) and change (which is to say, death). Impermanence, ephemerality, and transience are inherent in the title, the themes, and the little chocolate people filled with raspberry cream.

That last may seem out of place, but it’s not. This story is full of scenes stolen by Delirium. She is whimsical and wise, kind and cruel, confused and crystal clear. She thinks that viridian and twinkle are nice words, and she proves the truth of her earlier statement that she knows things that none of the other Endless do. She makes the whole story work.

Destruction, living on a Greek island with his dog Barnabas, tries the other side of his coin. He paints, writes poetry, sculpts, cooks (and does all of it badly, except possibly the cooking). And he tries not to know.

Bernie Capax shows us that all lives are brief. The Alderman turns into a bear, and bites off his own shadow, leaving us with a welter of images. Etain tells us that the things we get from dreams are free. And Ishtar reveals the sacred in what has now been debased.

We discover from Pharamond that Dream can give the advice that he cannot take: that one can stop being anything.

Most importantly of all, Dream becomes more vulnerable. He is changing so much that it is commented upon by nearly everyone he sees. His own doorkeepers almost do not recognize him. And he does the one thing that Desire has been trying to get him to do for many years now: he sheds family blood. This act of kindness, which he had sworn not to perform, is what marks Brief Lives as the turning point of the series. We have entered the third act. It’s all down hill from here.

Jill Thompson gives humanity, tenderness, and color to the artwork, aided by Vince Locke. Aside from the Zulli issues, Brief Lives contains my favorite artwork in the series, I think. Although this is one of Gaiman’s masculine stories, it’s the women who stand out visually, becoming more real than most of the other females who appear in The Sandman. Delirium, Despair, and Death, of course, but also Marie on reception, the widowed Mrs. Capax, Ruby the chauffeur, and the dancing goddess Ishtar.

Delirium has the most amazing quotes in this volume:

“You don’t want my name. Trust me. You really don’t. I don’t want my name, and I’m sort of used to it by now. It would really mess you up.”

“You know, if this car had great big runny legs like a centipede it could run very fast and we’d get there quicker.”

“Have you ever spent days and days and days making up flavors of ice cream that no one’s ever eaten before? Like chicken and telephone ice cream?”

Mervyn and Barnabas have lines nearly as good, if not so peculiar.

Having, perhaps, learned something from the too in-depth introduction in A Game of You, Peter Straub’s superb and insightful introduction is at the back of the book. Read it when you get there.

Over all, these three volumes are the center of the story of The Sandman. The first two are the foundations, setting the stage, filling things in a bit. The short stories are ornaments and embellishments (although some of them are integral to the overall structure). And the final two volumes are the capstone, the coda. If for no better reason (and there are better reasons) than this, treasure these three stories because they are the heart of something special.

Worlds’ End

This series of short stories was published in between Volumes 4 and 5 of the series proper.

When an unseasonable storm blows up, travelers from many worlds and plains are stranded. Through the trees, they see lights, an Inn. This is the World’s End, the Inn at the End of Worlds, one of four “free houses.” And, for the time being, there is nothing to do but sit around and tell stories. A creepy tale of the dreams of cities; a swashbuckling tale of the overthrow of a cruel lord; a stirring tale of the sea, and what lies beneath it; a “Horatio Alger story of some poor boy becoming president”; and the story of a funeral…. these are the stories we hear. How many others are told?

The Chaucerian framing sequences are all courtesy of the inestimable Bryan Talbot and Mark Buckingham, giving the Inn a warm and realistic feel.

The first story is the disturbing and mildly Lovecraftian “A Tale of Two Cities,” a title which the teller of the tale acknowledges as a nod to Dickens. It’s drawn by Alec Stevens. Robert loves his city, and wanders it compulsively. One day, he spots a silver road leading off through the marketplace. Working too late that night, he gets on the wrong subway train, a gleaming black and silver deco dream of a train with only one other passenger, a tall, thin, pale man in black. When he disembarks, he is no longer in the city he knows….

Next Clurican of Faerie steps up to tell a “bald and insipid narrative” of a charming (if somewhat rushed) tale of swashbuckling and intrigue. “Clurican’s Tale” is given lovely, stained-glass-like images by John Watkiss. The Queen of Faerie’s Envoy in Extraordinary is sent by his green monarch to ensure that the cities of the Plains do not unite. Arriving in Aurelia of the Plains, he finds that the monarch who wishes to unite them is rather a nasty sort. But Clurican of Faerie is a resourceful fellow…. While I always enjoy the story, it really needs to be at least twice as long. As it is, the clever ideas and wonderful little touches are rather too crowded together for comfort.

“Hob’s Leviathan” allows a young sailor in love with the sea to tell a Kipling-styled story in which old Hob Gadling appears. Ably aided by Michael Zulli and Dick Giordano, this tale of secrets, and regret, and sea magic jumps to life. The world of the tall ships is slipping away, and young Jim knows it. But the two passengers that Jim’s ship takes on have seen many things slip away, and they’ll leave Jim with a little of their wisdom when they go.

Michael Allred gives a shining nimbus to the mythologized tale “The Golden Boy,” a revival of a 1970s DC character named Prez, who became the US’s first teenage president. Prez knows two big things: one is America, and the other is time. Having fixed all the clocks in his hometown, he has moved on to fixing his country. His story is transformed into legend and myth almost as soon as it happens, quicker than even JFK was canonized. And, once he is dead, he becomes a story himself.

It’s not a political tale, even if it looks like it. Instead, it’s a story of how we view our leaders, how, while they’re in office, they’re awful, and once they’re gone, we love them. “In hindsight even Warren Gamaliel Harding looks good,” Prez’s predecessor tells him.

Now we reach “Cerements,” a tale which, perhaps, embodies the more abstract concepts behind the Sandman series more than any other issue. Shea Anton Pensa and Vince Locke depict a story designed like an Escher print. This is Petrefax’s story, the young man who is a journeyman in the Necropolis Litharge, the city where the death rituals of worlds are kept. Petrefax speaks of a funeral he attended on an assignment, where the ritual included storytelling. And when Master Hermas, who conducts the funeral, tells his tale, he speaks of the woman he learned his craft from, who once told him a tale of a coachful of prentices and a master, who were stranded by a storm at an inn where the price of haven was a tale. Here, at the sixth degree of separation, we find ourselves back where we started. And, design aside, we learn things in this tale about what happens when one of the Endless dies.

And in the final issue of Worlds’ End, we finally see what has caused the storm.

Stephen King introduces this volume.

This third and final collection of short stories was Gamain’s last pause for breath before plunging into the consequences of the events in Brief Lives. It was an opportunity for him to give us some last details, and get some last story ideas out of the way, and have some fun, before the final act and the coda. Hereafter there lies tragedy.

If you haven’t read The Sandman, if you don’t know what happens at the end of this story, if you want to be surprised, then stop reading now. Because there is no way to review the final two volumes of The Sandman without spoilers. Sorry about that.

The Kindly Ones

All around me darkness gathers,

Fading is the sun that shone;

We must speak of other matters:

You can be me when I’m gone.Flowers gathered in the morning,

Afternoon they blossom on,

Still are withered by the evening:

You can be me when I’m gone.

When Hippolyta Hall’s young son Daniel is kidnapped, she slips slowly into madness. Assuming that Dream has taken him, she goes searching for the goddesses who loaned her their name when she was a superhero: the Furies. These three ancient figures of vengeance prefer to be known as the Eumenides, here roughly translated as the Kindly Ones. Though the Ladies cannot avenge the supposed death of Daniel, they can, and will, avenge Dream’s mercy killing of his own son, Orpheus. The Eumenides are not empowered to kill Morpheus, but to drive him to suicide….

Many characters from the run of The Sandman make a reappearance or get a reference somewhere in the course of this book or the next, right down to a pair of dreamers who served at the feast in Season of Mists. In a symphony, the last movement draws on themes from all the previous movements, and so Gaiman does here.

So here is Rose Walker, once a vortex, who was baby-sitting Daniel when he was kidnapped. Here is Zelda the Spider Woman, facing her own transience. Here are Thessaly, and Hob Gadling, and Alexander Burgess, Mazikeen and Lucifer, Clurican and Mab, Loki and Puck, and a new Corinthian. Like Delirium when Orpheus was about to go to his rest, they pop in long enough to say “hello” and “goodbye.” Some do a little more….

The Kindly Ones is a tragedy. My Theater History professor used to say (quoting, I assume, but I don’t know whom) that a tragedy is where everybody who needs to, dies by the end. And, depending on your definition of “needs to,” I suppose that happens. Neil Gaiman, in his introduction to Endless Nights, says that he was asked to summarize the plot of The Sandman in twenty-five words or less. This is what he came up with: “The Lord of Dreams learns that one must change or die, and makes his decision.” And, in the end, that’s why he needs to die. He needs to shed his life and move on, because he can’t change enough. Partially for himself, and partially to make way for a new Dream, one who can change, and who can be what dreamers need him to be.

This is the longest of the ten volumes of The Sandman, comprising thirteen monthly issues. The story is intricately constructed, echoing other stories and itself again and again. It was never really designed to be read as a monthly, and so upset a lot of readers at the time, with its iconographic, impressionistic style of art (provided by Messrs. Marc Hempel, Richard Case, D’israeli, Teddy Kristiansen, Glyn Dillon, Charles Vess, Dean Ormston, and Kevin Nowlan), its peculiar continuity, and its lack of reintroductions. Gaiman knew when he wrote it that it would be collected, and he wrote for that book.

If you’ve read far enough in The Sandman to read this book, then I have no doubt that you’ll enjoy The Kindly Ones. But be ready to cry.

The Wake

“Somewhere in the night, entities bigger than storm-clouds are building a house of remembrance.

The people on the ground are waiting for the building to be finished before they go inside.

They wait awkwardly, shuffling and making small-talk, in the wasteland that was once the heart of the Dreaming.

Everybody’s here.

You’re here.”

Attend now the wake of His Darkness Lord Dream of the Endless. Spend the night swapping stories with dreamers and dreams, gods and monsters, from everywhere. Drink the wines that you find in dreams. Celebrate, and mourn. And, in the morning, attend the funeral service, and speak what is in your heart.

Months after the funeral held in dreams, Robbie Gadling attends a Renaissance Festival, and is offered a choice.

In the Desert of Lop, an old man meets both Dreams, the old and the new.

And, finally, we see the second of the two plays Will Shaxspar once promised Dream. The earlier was for Morpheus’ friends, Auberon and Titania. This one is for him. When asked why this tale, Dream replies, “I wanted a tale of graceful ends. I wanted a play about a King who drowns his books, and breaks his staff, and leaves his kingdom. About a magician who becomes a man. About a man who turns his back on magic.”

If The Sandman has been a symphony, then this is the coda. It is sweet, and sad, and ultimately it allows us to move on. We say goodbye to Dream, and to the characters we’ve enjoyed, and we say hello to the new Dream.

Because, of course, there is a new Dream. “How,” as Cain rhetorically asks, “can you kill an idea? How can you kill the personification of an action?” So whom do we mourn? “A puh-point of view,” stutters Abel.

The three issues which show the rituals of grieving for Morpheus give us glimpses of still more characters before the series ends, and allow us to mourn. Matthew the Raven speaks for us, and shows our anger at losing the Dream we know, and our resentment of his replacement.

“Sunday Mourning” shows us that life does go on, and how to heal, and gives us a bit of humor before we go. “You should spray ’em all with shit as they come through the gates,” rants Hob Gadling on how inauthentic the Renfest is. And he still thinks death is a mug’s game.

“Exiles” bridges the chasm between the old Dream and the new, and ties off an old subplot, and lets us visit the soft places one last time.

“The Tempest” shows us that Dream has been thinking about how to escape his responsibilities for a long, long time.

Read The Wake, and round your trip through Dream’s lands with waking.

A few final remarks on The Sandman:

Gaiman’s series has provided us with a modern mythology. There are many college students wandering around today who are a little fuzzy on Zeus and Athena, but they can name all seven of the Endless, and quote Gaiman as if he were Euripides (mind you, they’ll be able to name Loki’s first wife, but only because she’s in Sandman, and they’ll be surprised to hear that he had another). The Sandman is slowly sinking into the consciousness — and unconscious — of a generation, and providing them with a framework for examining themselves and their worlds. And I think that’s a good thing.

When you’re reading Sandman, read the introductions (though, often, you want to read them after you’ve finished the story), as they all say something interesting or insightful about the books. Some really rather illustrious folks have written introductions to Gaiman’s work. And read the biographical miscellania at the back. They’re pretty much always amusing.

I started reading The Sandman while The Kindly Ones was being published as a monthly. The first issue I read was #59, The Kindly Ones: 3, and it was an incredibly confusing place to come in. But that issue contains a quick survey of what the other Endless were doing, and I fell in love with Delirium and her singing fish. It took me something like two years to track down all of the volumes of The Sandman after that (particularly on a high school student’s small amount of pocket money), but the characters and the stories haunted me until I’d filled in all the gaps.

I’ve now been immersed in Sandman and Gaiman for a solid month. Reading and reviewing all ten volumes, plus one, doing my research in The Sandman Companion and on Neil’s Web site, picking up Jill Thompson’s Death manga digest, finally reading Adventures in the Dream Trade and watching Neverwhere (and, apparently, volunteering to review it), and participating in collaborative fan fiction (and Neil points to the ongoing saga there when he’s asked about good fanfic), I feel a bit like the narrator at the end of Milne’s Once on a Time. Now I can take all of those volumes off of my desk, where they’ve stood as a rampart between me and the world, behind which I’ve lived in far-off lands and days, surrounded by dreams.

Songer est mort, vive le songer.

(DC Comics, 1995)

(DC Comics, 1995)

(DC Comics, 1992)

(DC Comics, 1993)

(DC Comics, 1992)

(DC Comics, 1993)

(DC Comics, 1994)

(DC Comics, 1994)

(DC Comics, 1996)

(DC Comics, 1997)