It happens every so often that I find myself asked to write a “review” of something that is so deeply imbedded in our culture and such an integral part of our collective experience that my first impulse is to run off and find a place to hide. In the case of Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are (another of those children’s classics that I somehow escaped reading when I was a child), it was daunting, at least a little, but it was also a lot of fun.

It happens every so often that I find myself asked to write a “review” of something that is so deeply imbedded in our culture and such an integral part of our collective experience that my first impulse is to run off and find a place to hide. In the case of Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are (another of those children’s classics that I somehow escaped reading when I was a child), it was daunting, at least a little, but it was also a lot of fun.

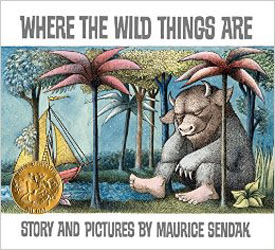

The story, as might be expected, is fairly straightforward. Max, after donning his wolf suit and creating enough mischief to tax anyone’s patience, is sent to bed without his supper. The redoubtable Max, however, waits calmly while a forest grows in his room until it is the world itself, complete with ocean and a private boat (and it is absolutely Max’s boat — it has his name on it), upon which he embarks to a far land where the wild things are. They are terrible indeed, but Max is unfazed and stares them down. Chastened, they choose him as their king, and then proceed to raise a rumpus under Max’s direction. But Max gets a little lonely for the comforts of home, and embarks once again on his boat, arriving in his room to discover his supper waiting.

Max is, in some ways, an avatar of Joseph W. Campbell’s archetypal Hero, although it’s not an exact fit. The elements — transformation, the journey, conquest of the adversary, triumphant return — are there, albeit shuffled (Max’s transformation marks the beginning of the story, not its climax) and subverted (Max returns, not to bring change to the community, but to resume his comfortable status quo ante). It’s a dream, of course, with all the fairy tale logic that implies. Campbell noted that the story of the Hero is also the story of the soul, but Max is a child: children may long for adventure, but what they crave is order and normalcy. It’s this insight into the soul of the child that makes Sendak’s work so compelling.

Sendak has been noted as an example of the “here-and-now” school of children’s literature, which is to say that he begins with everyday life, usually urban life, as his foundation. Here the urban element is almost nonexistent, but the circumstances are those with which any child can identify, and the events are those that children can accept at face value. It’s worth noting that Sendak seems here to inhabit the mind of the child, particularly that facility for acceptance: it took me a bit to realize just how bizarre it is that anyone has a wolf suit. (It’s a very nice suit, though.)

Sendak’s art reinforces the story in any number of ways, from the wild things themselves, composed of parts of everyday animals combined in bizarre arrangements (my favorite, I think, is the one with the bull’s head and enormous human feet), all, of course, showing rows of sharp teeth and long claws, to the narrative line that the drawing supports and in some sections continues on its own. (The rumpus is one of the most sedate and well-behaved on record, I think, and Sendak’s drawing catches the nuances as well as the broad strokes.) The monstrous quality is, to a certain extent a sham, at least from this adult’s viewpont: Max has no trouble facing down the wild things and rapidly becomes their leader. The artless quality of Sendak’s drawing reinforces the sense of a child’s way of seeing.

And it’s funny. I am not one given to laughing aloud at what I’m reading, but this one had me going. The humor is fairly subtle in many places — Max’s facial expressions are priceless — but the cumulative effect is quite hilarious.

Where the Wild Things Are is quite deservedly a classic. I can’t think why it took me so long to read it.

(HarperCollins, 1963)