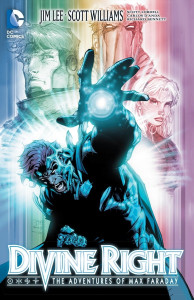

Part of the problem with Divine Right: The Adventures of Max Faraday, is that we’ve seen it before, and better. We’ve seen it with the Beyonder, for one. Molecule Man, for another. Any comics junkie is going to be more than familiar with the notion of the all-powerful dweeb whose universe-spanning power is moderated by the love of a good, if large-breasted and incredibly good-looking woman. Max Faraday falls neatly into this category, a nerd who accidentally downloads into his brain most of the code that enables him to modify reality at will. The rest he sends off to his online girlfriend, Susanna Chaste (obvious name symbolism alert!) who, in addition to being what the kids refer to these days as a smokin’ hottie, is also a nerdette with no social life who nonetheless is madly in love with our hero, Max.

Part of the problem with Divine Right: The Adventures of Max Faraday, is that we’ve seen it before, and better. We’ve seen it with the Beyonder, for one. Molecule Man, for another. Any comics junkie is going to be more than familiar with the notion of the all-powerful dweeb whose universe-spanning power is moderated by the love of a good, if large-breasted and incredibly good-looking woman. Max Faraday falls neatly into this category, a nerd who accidentally downloads into his brain most of the code that enables him to modify reality at will. The rest he sends off to his online girlfriend, Susanna Chaste (obvious name symbolism alert!) who, in addition to being what the kids refer to these days as a smokin’ hottie, is also a nerdette with no social life who nonetheless is madly in love with our hero, Max.

And if that’s all there were to it, fine. It’s an old trope, but one that can be worked with effectively.

Except, of course, that it isn’t effective, because in addition to its tired origins, Divine Right is also heir to some of Wildstorm’s worst excesses. Hypersexualized character concepts? Check. Creepy brother-sister incest implications? Check. Gratuitous head explosions, skimpy costumes, and obfuscatory growly macho dialogue? Check, check and check. And of course, mandatory crossover throwdown between every superteam available. Wearily, finally, check.

One gets the feeling that Divine Right was put together as a way of tying together multiple plot threads from the various Wildstorm titles. There certainly are enough in here: Coda assassins, the Rath, Gen 13, WildC.A.T.S., and so forth. If that makes your head spin, then you don’t want to dive any further into this one, because much of the series (12 issues, collected into two graphic novels) consists of lengthy bits of exposition disguised as on-the-nose dialogue wherein the whole thing gets laid out. Sort of.

The plot, such as it is, involves a massive alien artifact called the Creation Wheel that happened to crash-land in the Middle East once upon a time, the heavenly VR world it created for no particular reason, and the efforts of various factions and critters within the Wildstorm universe to control the power the Creation Wheel represents. But it’s poor hapless Max, with his goofball best buddy, cyber-heavy love life, and zaftig sister who vamps around in her underwear, who ends up with it. That means everyone who was after the power starts chasing after Max, at least until he figures out how to use the power, at which point, well, they’re still after Max. Everyone, that is, except for his girlfriend, who liked him better before he had huge cosmic powers.

It all ends with a messy and pointless throwdown – literally pointless, as the various super-teams go at each other (with one of them mind-controlled) until another character says “Enough” and breaks Max’s telepathic hold, something he could have done at any time. Then Susannah shows up, armed with oversized weaponry and the conviction that only she can stop Max because he loves her, and thus will allow her to get close enough to filet him and save the universe. Only he doesn’t, and the way it works out, complete with nonsensical happy ending, veers between overwritten and underexplained.

Really, the biggest problem with the series is Max. Ostensibly an archetypal Peter Parker-like loser, he adapts to having complete control over the universe (and an attitude to match) in about six lines of dialogue. There’s pretty much no character evolution, no pondering of what he’s turning into, no self-reflection as to what he might or might not do. He just starts spouting brutish one-liners and metamorphoses himself into a heavily muscled Captain Atom clone. His declarations of godhood are whiny and unbelievable, his “self-realization” moment at the end entirely too convenient, and his uses of his powers pretty much sadly pedestrian.

God, ultimately, should be interesting, even if he’s really a nerd with a soft spot for old movies. Therein lies the ultimate failure of Divine Right. The rest, like the devil, is in the details.

(Wildstorm, 2002)