Salvation gives us an intermezzo within the story of Jesse Custer’s search for God. In Jesse’s case, the search is literal: he has some things to say to the Almighty. But there are things, it seems, he must do along the way.

Salvation gives us an intermezzo within the story of Jesse Custer’s search for God. In Jesse’s case, the search is literal: he has some things to say to the Almighty. But there are things, it seems, he must do along the way.

Jesse, who has somehow lost an eye and acquired a dog — he doesn’t remember the circumstances — finds himself in Salvation, Texas, a small — well, it’s not exactly a company town, but the company, a meat-packing plant owned by one Odin Quincannon, uses the town of Salvation for workers’ R&R. The townsfolk may or may not like the idea, but Quincannon has bought everyone he needs to buy to keep it that way. After Jesse takes out a group of company men who are harassing a girl (who, as it happens, is Lorie Bobbs, the sister of his childhood friend, Billy-Bob), the sheriff sees an opportunity. Handing over his badge, he makes tracks to depart, leaving Jesse as the sheriff of Salvation. Jesse, true to form, does the best job he can, and doesn’t really care whose toes he steps on. The first, as it happens, are Qincannon’s.

Ennis has dropped the story right back into the classic Western of the new-sheriff-in-corrupt-town category, all within the context of the absurdist black comedy that is Preacher. Add in a little bit (well, OK, more than a little) of the racial tensions one might find in a small town in Texas — it only complicates matters that Jesse’s depputy, Cindy Daggett, is a black woman who’s better at the job than the previous sheriff was — and we’ve got the set-up for one of Garth Ennis’ intense, no-holds-barred dissections of modern America.

And yet it’s not all grotesqueries and black humor, although both are still major elements. This is a talky volume, at least by comparison to the other collections, but it’s all to the point: Ennis is laying out the foundations for us, and manages to do so in a way that doesn’t impede the flow at all. And, after his job in Salvation is done, Jesse heads for New York. On the way, he takes a break with a bit of peyote in an attempt to close the gap in his memory. It works.

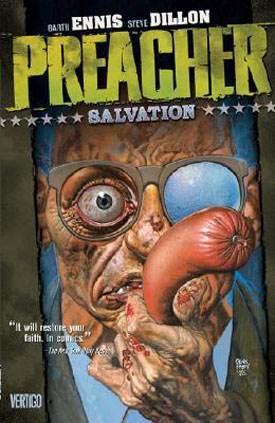

As has been the case throughout, Steve Dillon’s art is right in line with the story, and adds a dimension of its own: Dillon manages to open up the characters for us in a way that dialogue simply can’t. The illustrations are full of little details, facial expressions, body language, that fill out the dialogue and add even more depth to the story.

This is, by necessity, merely a sketch. There are subplots, flashbacks, references and resonances throughout that tie together what is, after all, a large, sprawling epic. It finishes off with another reminiscence by Jesse’s father’s friend from Vietnam, Spaceman, which takes place at the Vietnam Memorial in Washington. It’s a nice coda, and helps to explain why Jesse is who he is.

And now, for the grand finale: just click through for Preacher: All Hell’s A-Coming and Alamo.

(Vertigo/DC Comics, 1999) Collects Preacher #41-50.