Debbie Skolnik wrote this review.

Debbie Skolnik wrote this review.

How do you add a new dimension to (and perhaps the enthusiasm of a new generation for) the wonderful world of folk ballads and sagas? One solution is to use an art form that is not usually associated with such things. In this case, I speak of the comic book, or as it is more usually known these days, the graphic novel.

Charles Vess, an extremely talented graphic artist, has done just that. Vess, who has a solid reputation for illustrating such works as Neil Gaiman’s Sandman stories (also published in graphic novel form) also loves the ballads and sagas that have been entertaining people for hundreds of years, and in this series of books he has collaborated with some of the best-known writers in fantasy literature, including Gaiman, Jane Yolen, Charles de Lint, Sharyn McCrumb (not a fantasy writer but an author of mysteries with an Appalachian folkloric theme), Midori Snyder, Robert Walton and Delia Sherman (whew!) — I hope I’ve not left anyone out! They tell the stories: he does the illustrations.

The ballads are English and Scottish; the sagas are, as their name implies, Norse in origin. There are more ballads than sagas. Actually, there’s only one saga: Skade. Being enthralled by the English and Scottish ballads myself, I am quite familiar with all the stories. Norse mythology, however, I know very little about, so I did a little bit of quick research to familiarize myself with the basic story.

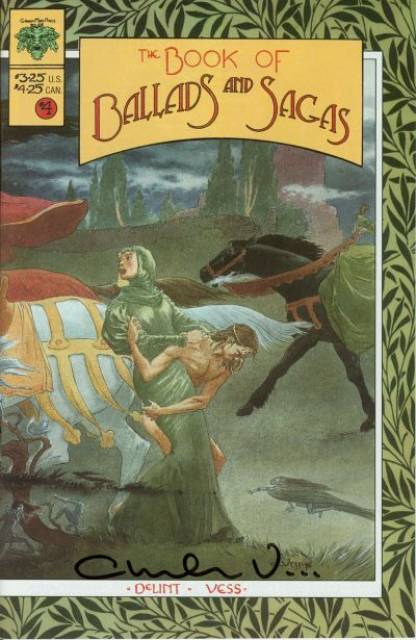

Each book has full color illustrations on front and back, with black and white illustrations within. Most of the illustrations appear to be pen and ink, but every so often (as with the last illustration in “Thomas The Rhymer,” Vess appears to mix his media, using either black pencil and/or charcoal to provide texture and shading.

The color illustrations are superb; there’s no other word for them. The black and white mostly pen-and-ink illustrations vary in complexity; I did note a few that appear to be done in a mixture of pen-and-ink and black pencil, as the shading is softer. They vary in size, from full pages to small insets on other pages. Some are pure black and white; others have lots of texture. I would have liked to see these drawings in a larger format, and to be honest, I would have liked more in color. I know many of the stories are dark in nature, and black is a natural color to imply this, but after a while my eyes started to fatigue. I also know that reproducing color is far more expensive, and I’d bet that was a consideration as well.

Book #1 starts out with one of my very favorite Child ballads, “Thomas The Rhymer,” the story of a man who is swept away by the Queen of Fairies to live in Elfland. If he manages to stay silent for seven long years, he will be returned to the world of man. Thomas manages to do just that, and as a reward for doing so, he is given the gift of prophecy by the Queen, as well as the promise that she will return for him at some time. He is an old, old man when she finally appears, but she takes him back with her to Elfland, a journey he makes quite happily. Text is by Sharyn McCrumb. If you’re fond of the story of Thomas The Rhymer, Ellen Kushner has done a wonderful version of the story in her book of the same name, which I have previously reviewed.

Following “Thomas The Rhymer” is another Child ballad, “The False Knight Upon The Road,” which tells the tale of a young boy on his way to school who encounters the devil in the guise of a knight on the path. This is, of course, nothing more nor less than the age-old battle between good and evil, and in this case, the knight and the boy parry with a series of barbed verbal exchanges. Good triumphs over evil; the boy stands firm, and the devil is vanquished.

Vess then changes cultures to tell the Norse saga of Skade. I have to confess that I have a lot more trouble following the story line in this one, largely because I didn’t know it beforehand. In fact, I would make that a comment about the series in general: if all I had to go on were the graphic illustrations, would I fully comprehend the story based on the illustrations and dialogue? I’m not sure the answer is “Yes.” Luckily the full text of a version of each ballad or saga is included in the book. I personally find it easier to follow the story without the graphics, but maybe that’s just me.

Enriching the graphic tellings of these tales is a reprint of a wonderful essay on the ballad form by Terri Windling called “The Music of Faery,” which first appeared in Realms of Fantasy in 1994. It is studded with examples of the stories and the music (and musicians) who have brought this all to life. Ken Roseman provides discographic notes, and Vess promises that Roseman will interview some of the musicians in later issues of the series.

Issue #2 starts with “King Henry,” (Child #32) whose encounter with a fearsome female ghost ends with her magical transformation into a beautiful woman.

“Sovay” tells the tale of a woman determined to test the faithfulness of her lover, Willie. She disguises herself as a robber and demands that Willie hand over the diamond ring that she has given him as a token of her love. He passes the test, refusing to surrender the ring, and is rewarded by Sovay’s doffing her disguise and spending the night with him.

Another episode of Skade rounds out the book. There is also a brief essay entitled “Ballad Musings,” which provides both written and musical resources for those who want to delve further into the wondrous world of balladry. As with the first issue, there are discographic notes. Vess admits he planned to include two more ballads, “The Galtee Farmer,” and “Barbara Allen,” but bad weather forced him to alter his plans.

Issue #3 makes good on that promise, including as well “The Daemon Lover,” an essay on Southern folk ballads by W.K. McNeil, and another discography by Ken Roseman. There is no installment of “Skade” in this issue, but Vess includes one of his own creations, “Scarecrow.” Set in Kansas, the opening illustrations remind me of nothing so much as the beginning of the “Wizard Of Oz.” A carnival run by a witch comes to visit a small town, and one of the locals, Harklin, besotted by her, pays her a visit one night. He was seen leaving her trailer wild-eyed, and he took to drinking and talking nonsense. After the carnival leaves town, a scarecrow mysteriously appears, and two young boys decide, as young boys do, to liberate the scarecrow from its perch. This doesn’t seem like fun for long, since they soon notice a foul odor and mysterious shapes in the vicinity. They abandon the scarecrow. Coincidentally, Harklin disappears, and no trace of him is ever found.

Vess offers a miscellany of his other work for your delight. He includes illustrations of Aladdin (and his Wonderful Lamp), Cinderella, and The Velveteen Rabbit, to name a few.

The final issue, #4, starts out with one of my other favorite Child Ballads, Tam Lin (#39). For me the definitive recording of this song was done by Fairport Conventionon their seminal album, Liege and Lief: Sandy Denny’s vocals are as otherworldly as the story. A young noblewoman is beguiled by handsome Tam Lin, and becomes pregnant by him. She learns that he was once a human knight, but he is caught by the Queen of the Fairies and taken away to Fairyland. He worries that a ritual sacrifice at the end of seven years might mean his death, but Janet agrees to help him escape the Queen. On Halloween, she is to pull him off his horse, and despite his shape-shifting into horrible beasts, must hold firm to him. If she can do this, the enchantment is broken. She is true to her word, and although the Queen of Fairies realizes what trick has been played on her, she is now powerless with regard to Tam Lin.

The story of “Twa Corbies” (Two Crows) is next. The text is by Charles de Lint, and if you have read any of his stories, your keen eye will catch references to his own world and characters in this telling. It’s a grisly story: two crows are discussing what to have for dinner. Carrion is, of course, their favorite food, and they decide that a newly-deceased knight will make the perfect meal.

Ken Roseman interviews Bob Johnson of Steeleye Span about the groups’ continued fondness for traditional ballads. Careful readers will note that Steeleye Span has recorded a version of almost all the ballads in this series of books. We’ve got lots of Steeleye Span reviews here at Green Man Review, by the way. (For example, see our reviews of A Rare Collection 1972-1996; Horkstow Grange; Please To See The King; Steeleye Span In Concert; and Time.)

This last book in the series ends with a preview of a new strip done by one of Vess’s friends, Linda Medley. The strip is called Castle Waiting. To be honest, it didn’t catch my fancy.

Although I don’t think that everything contained in this series is a total success, there is nothing quite like it out there that I’m aware of. If you are a fan of graphic novels, fantasy writers, or traditional ballads and sagas, then I definitely think these books are worth seeking out.

There is a compilation of many of the ballads from the four works reviewed above called The Ballads trade paper edition, with an updated bibliography by Ken Roseman, available directly from Vess. He can be reached through his Web site, which is a great place to have a look at Vess’s drawings and learn about all the projects in which he’s involved.

Editors Note: The Book of Ballads and Sagas was originally intended as a six issue series, but a number of reasons over the years conspired to keep Vess from finishing the series but it they are in The Book of Ballads printed bt Tor some years later.

(Green Man Press, 1992 – 1997)