In a recent interview, cartoonist (and the designer of the Complete Peanuts books) Seth described the appeal of Charles Schulz’s iconic comic strip.

In a recent interview, cartoonist (and the designer of the Complete Peanuts books) Seth described the appeal of Charles Schulz’s iconic comic strip.

Schulz was a premier influence on me. Ever since I was a little kid, I’ve loved Schulz. He’s just been such a constant experience in my life. I read him all my childhood and my teen years. And then in my 20s, I sort of reevaluated the work. That’s when I started to look a little more deeply into why I liked the work. And Schulz’s work just had a profound effect on me as an artist. The utter simplicity in how he drew sort of infused itself into me, and I can really appreciate that sort of instinctive way he has. It’s as though his way of drawing isn’t just drawing. Those characters are almost representations of his own psyche or something. He’s managed to infuse the characters with more depth than most cartoon characters have. It’s beyond the material itself, there’s something in the actual manner in which he drew them. They’re more like his handwriting than they are like designs. And it’s really appealing on a basic cartooning level to look at Schulz’s work and see that he was a master cartoonist who understood how to really communicate ideas. I can look at it endlessly and learn from it. But then on the flipside of that, I think his work is extremely touching. I think the Peanuts strips are very funny, and they have a surface quality to them that people have just sort of absorbed, without thinking about it. But over like the 50 years of that strip, I think he really managed to create something very moving. I think that and Krazy Kat — maybe a couple of other choices would be in there — but I think it’s certainly among the best comic strips ever written.

“Among the best comic strips ever written.” That’s an interesting way to describe a comic strip, but totally appropriate, because there are many strips which are better drawn, but the key to the longevity of Peanuts is the way that it was written. Set in an unnamed town someplace in the USA, a group of children experience life through interaction, through play, imagination and fantasy. They’re not always very nice to each other but they are always honest, and open, and they are real. Real in a way that comic strips which strive for reality have never been. There are no super heroes. Adults exist, but are never seen. The dog talks, and has possibly the greatest imagination of them all. And yet Snoopy is a perfect representation of a dog. I’ve measured my shih tzu against this beagle, and I can see Chloe in the actions of Snoopy, time and again. Right down to Snoopy’s lying on the peak of his doghouse (believe it or not). Okay, Chloe never stretched out prone on her doghouse roof, but she did recline, quite comfortably on the top of the couch in front of the window, precariously balanced, but wonderfully relaxed. And she dreams. I know she dreams. Is it about being a snake? Or a vulture? I don’t know. But you can watch her as she sleeps and know that she is running in a field, chasing a rabbit, or having some other adventure in her mind.

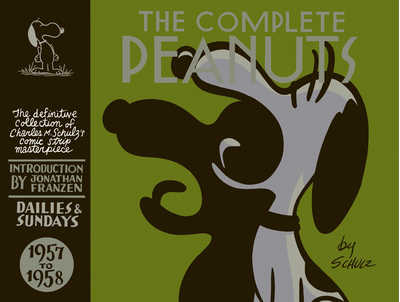

Snoopy is the featured character on the cover of The Complete Peanuts 1957-1958, just as Charlie Brown, Lucy, and Pigpen have gone before. And the essay in this volume was written by Jonathan Frantzen. Fascinating stuff, but the essence of each of these books is the chronological reproduction, on good paper stock, of the daily strips, and the corresponding Sunday strip. They read like short stories. A theme is carried on for a few days, and then Schulz moved on. He might return to the theme later, but ideas were not milked dry. There were always new adventures for the kids.

Linus grows up, and begins his life as the residential philosopher. Charlie Brown continues to try to kick the football, or fly his kite, only to be disappointed. The baseball team is humiliated. And Snoopy speeds through life in the fast lane, in fantasy. He also has his dog days, when he in humbled by having to be served his dinner.

I said that there were better drawn strips, but Schulz’s nimble sketches are perfect for conveying the simplicity of this community. Over 100 of the strips included here have never been reprinted since they first appeared. The drawings are timeless. And so are the stories. There are many more volumes to come. I treasure the four on my shelf and look forward to the rest.

(Fantagraphics/Raincoast, 2005)