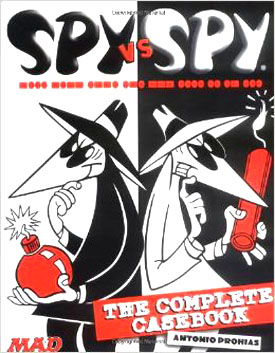

Those of us who remember Mad magazine in the 1960s and ’70s also remember “Spy vs. Spy,” Antonio Prohias’ ongoing series about the Black Spy and the White Spy (and sometimes the Gray Spy, a female counterpart, as well) who spent their time thinking up outlandish, Rube Goldberg-style ways to do each other in. (The Gray Spy, when she appeared, invariably won these contests — Prohias was chivalrous as well as funny.)

Those of us who remember Mad magazine in the 1960s and ’70s also remember “Spy vs. Spy,” Antonio Prohias’ ongoing series about the Black Spy and the White Spy (and sometimes the Gray Spy, a female counterpart, as well) who spent their time thinking up outlandish, Rube Goldberg-style ways to do each other in. (The Gray Spy, when she appeared, invariably won these contests — Prohias was chivalrous as well as funny.)

The series was a mordantly satirical comment on the lunacy of the Cold War, by a political cartoonist whose biting wit made the Batista regime of his native Cuba somewhat uncomfortable, and the new, “democratic” regime of Fidel Castro even more so: Prohias fled the country in May, 1960; his wife and children escaped shortly thereafter. (Why is it, do you suppose, that charismatic, visionary leaders have such thin skins?)

The fascinating part of this book is the Introduction by Grant Geissman, which is actually a short biography of Prohias. His father looked down on his artistic endeavors, so Prohias, even in childhood not terribly responsive to authority, pursued them in secret. He began publishing his cartoons in the late 1930s, while still in his teens; by the late 1940s he was being published by every major newspaper and several magazines in Cuba. Even under the repressive dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, his satirical cartoons were popular and he was in high demand. Strangely enough, after the revolution, he started losing work. When he fled to New York, he approached the editors of Mad and was immediately hired on a free-lance basis (although for a while he had his own desk at the office). There is a short segment titled “A Cartoonist in Times of Revolution and Censorship” that details Prohias’ circumstances under Castro that fills in more detail, and a short piece by his daughter, Marta Rosa Pizarro, that fills in more detail on Prohias the man.

The cartoons themselves begin with an early series of Prohias’ first ongoing character, El Hombre Siniestro, “The Sinister Man,” a somewhat mischievous and sometimes repellent character. There’s a certain element of surrealism in these images that seems to be part and parcel of Latin American literature and art, and that makes the satire that much sharper.

One aspect of Prohias’ work that I found gratifying: he early on eschewed the use of dialogue and narration. The content rests completely on the images, something that holds true throughout his career, including early series, “Spy vs. Spy,” and later creations. And the images carry the narrative content beautifully.

To be honest, the full “Spy vs. Spy” series is not something to view in one sitting, or even several: it’s essentially the same gag over and over again, and the repetition becomes obvious. It helped, I think, that I was originally seeing it on a monthly basis. The book is worth having, though, for a look at Prohias’ early works and some of his later forays into not only political satire, but commentaries on human foibles (“Mad Blooming Idiosyncracies”).

It’s a volume well worth having, though, not only as an historical document, but as a primer on the possibilities of cartoons.

(Watson-Guptill Publications, 2001)