Jasmine Johnston wrote this review.

Jasmine Johnston wrote this review.

‘Quis custodiet ipsos custodies?’ (Who watches the watchmen?) – Juvenal

Have you ever read a book, a long book, all in one sitting, one gulp, one go? Till your eyes stick with every blink, and your bottom has pins and needles, and your calves are cramping, and your pinkie finger has been stained a permanent reddish-grey from rubbing inky pages open, and you’ve simply forgotten — not just ignored but really forgotten — all the pressing appointments of the day? Till you’ve lost all sense of purpose or self?

Yeah . . . I have. And it was Alan Moore’s Watchmen Complete, #1-#12, that did it. I guess I should be grateful that I encountered this little phenomenon long after the published fact, and thus the story arc has been completed. Else I’d be driven to weeping, as Susanna Clarke has charmingly quoted Jonathan Ross, at the release of every new issue.

The story is a reworking of American superhero culture into a realistic meta-narrative chronicling the rise and fall of the masked heroes. Moore backgrounds classic campy superhero stuff with a gritty alternative history, one that has been shaped by the unknowing collaboration of an uber-physicist and a Nietzschian superman. Their abilities alter the course of human technological development, polarising world politics into Socialist versus neo-Nazi sentiment, with a group of flabby, depressed retired heroes shoe-horned in-between. The story emerges in pieces, working backwards and forwards through time, bringing separate lives and incidents into a classic epiphany of horror and destruction — zounds! — and perhaps renewal.

A few key characters provide cohesion to this largely non-linear mystery plot. The superhero formerly known as the Nite Owl and former superheroine Silk Spectre are the humanizing element, and the youngest of the retired masked heroes. They took over their superhero identities from the first generation of vigilantes, and like the X-Generation, they find themselves suspended in limbo between youth and age, inheriting the sins of the previous generation but none of the benefits. They live in a post-heroic world, where superheroes were outlawed by a failing state, where individual rights have ossified into moral paralysis. The contrast between totalitarianism and anarchy, with consumerism the only realistic stabilizing force, is as accurate a parody of our global past, present and future as Orwell’s 1984 or Philip K. Dick’s The Minority Report. In this climate of chaos and compromise, Nite Owl’s and Silk Spectre’s motives are pure. Their search for justice despite their powerless position is, though ineffective, essential.

Minor characters often provide essential layers of meaning. In particular, the dialogue involving a newsstand owner, various customers, wired neo-Nazis and so on, and a sort of bassline delivery of the shipwreck comic narrative reads like the maniacal, cacophonic dialogue between the mad King Lear, the Fool, and the fugitive Edgar pretending insanity: disjointed voices vying for cogency and failing completely, wildly, profoundly.

The motives of nearly all the other characters are polarized, yet opaque: Jon the uber-physicist, Rorschach the maverick (his name taken from the real life psychologist who accessed the subconscious via symmetrical ink blots, which are kept a secret to this day), Ozymandias the golden boy. It’s difficult to tell who’s a sociopath and who’s perfectly sane and just evil.

It’s also difficult to tell when something is, but the flashbacks and interwoven texts tighten into a coherent blow ’em apart conspiracy replete with mutants, monsters, pirates, furries, murderers and crystal cathedrals in outer space. As the history of the superhero collective is revealed via ‘documents’ inserted into the text and via real-time conversations about memory, it becomes clear that government tactics of violence and propaganda are mirrored in the lives and choices of the superheroes.

These ‘documents’ also slowly uncover a heinous plan: the ultimate megalomaniacal re-creation of reality, where violence and propaganda are taken to the sort of extreme rendered by James Bond-type villains (‘Pinky, tonight I shall conquer the world!’), dictators, and corporate advertisers. The contrast between good and evil becomes a matter — for both sides — of controlling perception, and thus values such as ‘good’ and ‘destiny’ disintegrate, and are deconstructed, into mere cynicism and despair.

Part of Moore’s charm, I think, is this multiple-narrative collage. In addition to the classic comic frames of Dave Gibbons, Moore inserts prose excerpts such as marketing memos and letters, an autobiography, news-clipping scrapbook, ornithological essay, political commentary, and an essay rant upon the arts of a comic book writer. These texts bookend the visual episodes and inform both theme and plot. This post-modern technique counterbalances the meta-narrative frame, so that even the structure of the novel mirrors the conflict between supposed opposites.

Within the visual episodes, Moore also embeds a retro black-and-white comic book tale of a stranded mariner who falls into delusional psychosis, and the journal entries of a masked hero who also finds psychosis — perfectly horrible and darkly funny.

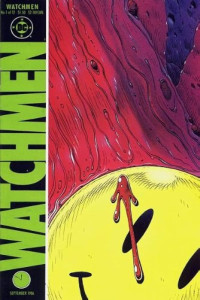

The visuals themselves are interesting. At first they don’t seem as revolutionary as the beautiful Sandman or the noir Bones, but they creep into the optic nerves and then send off shocks of form and colour. Episode one shows the cinematic close-up of blood being washed down a city drain; the pool of blood shrinks, but you realise that the ocular is ascending, until it reaches the perspective of the narrator, on the top of a high rise. Episode ten shows a grotty bar interrogation scene — just humdrum lowlifes and a few emotive close-ups — but coloured by John Higgins in a way that suggests a unity of brutality within a kaleidoscope of chaos, using low luminosity, high saturation rainbow colours: carmine red, mustard yellow, rotted orange, olive green, inky blue and puce. Movement is rife, and riffling, within the frames — the focus always shifting, perspectives dilating, copulating human proportions awkward, bulgingly vulgar and therefore hyper-real. Things fuse, explode, bleed, zoom, rot, gargantuate, freeze, and melt with a violence that is, as the truism goes, beautiful.

All that is consonant with the story, which is speculative and visionary in a paranoid, cautionary sort of way, and also no less ambitious than contemplating the reason for existence, the meaning of life, the miracle of humans being. Moore replaces dichotomies with elementals, propaganda with questions, despair with love. Evil versus good is replaced by fate versus freedom (a common motif in his work), and the creation of the sole responsibility of the individual to act.

So Juvenal’s reply? Perhaps ‘Vitam impedere vero’ (to risk one’s life for the truth). Or perhaps Pascal’s precept would be more accurate: ‘We desire truth, and find within ourselves only uncertainty: we seek happiness, and find only misery and death. We cannot but desire truth and happiness, and are incapable of certainty or happiness.’

Anyway, I recommend the whole trip of a graphic novel, to be read slowly — or all at once. It is rich in meaning, in imagination, in visual and verbal motifs, to dizzying degree. Watch the Rorschach blobs, the embracing lovers, the viscous gloss of moving blood, the clock. Moore is ambitious and he set a remarkable standard. My favourite episodes are four and ten — the monologue-driven time travel of the first and the sheer colour and energy of the second are pleasing and meaningful to degrees usually reserved for tosh such as War and Peace. And reading the more relevant Watchmen should take considerably less time.

(DC Comics, 1987)