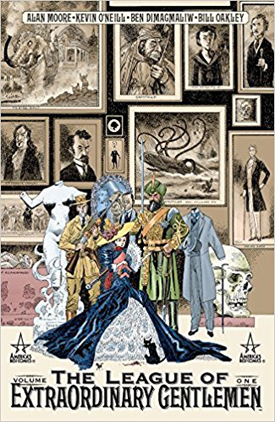

Who among us hasn’t, at one time or another, played the “What if….” game with characters, ideas or settings we’ve found particularly appealing? Maybe we spin out a colourful yarn in our head, or if we’re inspired enough, we put brush to canvas, hand to clay, or pen to paper. What results may vary in style or quality, but is unswervingly a creative act of adoration. In the hands of an eager teen, we might end up with schlocky, overeager fan fiction. But in the able hands of Alan Moore (story) and Kevin O’Neill (art) we are treated to The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, a six-issue comic originally released between 1999-2000 and since re-released in a single graphic novel edition in 2002.

Moore and O’Neill’s premise is simple but elegant: bring together a motley crew of Victorian literary characters and drop them into a delightfully pulpy penny-dreadful. And so we have H. Rider Haggard’s Allan Quatermain, Bram Stoker’s Mina Murray (Harker), Robert Lewis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Jules Vernes’s Captain Nemo, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Professor Moriarity, H. G. Wells’ Invisible Man, Edgar Alan Poe’s August Dupin and Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu all rubbing shoulders in a Victorian England (and briefly Egypt and Paris) of Moore’s own devising.

Moore and O’Neill’s premise is simple but elegant: bring together a motley crew of Victorian literary characters and drop them into a delightfully pulpy penny-dreadful. And so we have H. Rider Haggard’s Allan Quatermain, Bram Stoker’s Mina Murray (Harker), Robert Lewis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Jules Vernes’s Captain Nemo, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Professor Moriarity, H. G. Wells’ Invisible Man, Edgar Alan Poe’s August Dupin and Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu all rubbing shoulders in a Victorian England (and briefly Egypt and Paris) of Moore’s own devising.

Moore has taken a few liberties with the characters — Mina has divorced Johnathan Harker and goes by her maiden name of Murray, Quatermain is a laudanum addict — but nothing truly egregious or unforgivable. It’s all in the name of good storytelling. In fact, Moore takes great pains to explain Quatermain’s situation with a short story, “Alan and the Sundered Veil,” that is serialized each issue.

The story is itself a ripping yarn: Mina has been directed by the mysterious M (via his underling Campion Bond, a creation of Moore’s) to gather the disparate members of the League and then retrieve a stolen container of cavorite, a material with anti-gravity properties. The first two issues of the chase find Mina traveling first to Egypt, to retrieve an ailing Quatermain. Aboard Nemo’s fantastical Nautilus, they head to Paris, for the timid Dr. Jekyll and the monstrous Mr. Hyde. Last to be collected is Griffin Hawley, the Invisible Man, who’s found himself a comfortable role as mysterious ravisher of boarding school girls. The ensuing four issues unveil the League’s efforts to retrieve the cavorite from Dr. Fu Manchu, who has set up residency in Limehouse, and reveal the true nature of the quintet’s boss.

Verbal and visual references to Victoriana — literary and historical — are rife throughout the comics. Particularly amusing are the ads at the end of each issue, trumpeting cure-all elixirs, ear caps and electropathic belts, among other such quaint items. Moore and O’Neill clearly had a good time putting the League together. O’Neill’s art pairs well with Moore’s quick-witted dialogue, dark and angular against sharp and pithy.

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen should not be dismissed as merely pastiche, or as simply a clever comic. It’s an intelligent, rollicking good read that leaves you wanting more (how handy that the pair are already up to issue six of the second League series!).

But the constant Victorian references can be overwhelming at times, especially if you’re not too familiar with the era. Jess Nevins’ recently published guide to The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen is a definite labour of love (and must have involved many hours with a magnifying glass in one hand and reference books in the other) that helps explain the Victoriana in the comic. Clearly well-versed in all things Victorian, Nevins has turned his online annotations into a full-fledged “companion” to Moore and O’Neill’s comic series. His work is meticulous, digging up the historical or literary references behind partially scribbled words in a dark 1/8th page panel that most of us would have overlooked, and displaying a keen mind for obscure allusions. Occasionally he goes a bit astray with his assumptions, his fanciful thoughts brought back to earth by O’Neill’s side notes indicating what he and Moore actually intended (or didn’t intend).

But the constant Victorian references can be overwhelming at times, especially if you’re not too familiar with the era. Jess Nevins’ recently published guide to The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen is a definite labour of love (and must have involved many hours with a magnifying glass in one hand and reference books in the other) that helps explain the Victoriana in the comic. Clearly well-versed in all things Victorian, Nevins has turned his online annotations into a full-fledged “companion” to Moore and O’Neill’s comic series. His work is meticulous, digging up the historical or literary references behind partially scribbled words in a dark 1/8th page panel that most of us would have overlooked, and displaying a keen mind for obscure allusions. Occasionally he goes a bit astray with his assumptions, his fanciful thoughts brought back to earth by O’Neill’s side notes indicating what he and Moore actually intended (or didn’t intend).

There’s a wealth of information in Nevins’ guide, most of it useful for illuminating the dark corners of Moore and O’Neill’s work, and all of it interesting and entertaining. It’s an enjoyable read alongside the comics, an excellent complement. Though if you own the original individual issues (as I do), you’ll be frustrated that the guide refers only to pages in the graphic novel version. It’s difficult to flip back and forth between the guide and pages that don’t match up. Nevins was careful to review extra materials found only in the individual issues, so it would have been a nice touch to include page numbers for the guide as a whole (especially since the online guide refers to the original pages).

The guide could also have benefited from a bit of judicious editing, to tighten up Nevins’ prose. This is particularly evident in the essays included at the back — “Archetypes,” “On Crossovers” and “Yellow Perils.” They’re chock full of useful information, but somewhat on the rambling side, as if they were first drafts, rather than a finished product.

Bracketing the annotations and essays are a tongue-in-cheek introduction by Moore and a transcript of a phone interview between Nevins and Moore wherein they discuss the League’s origins and story in more detail. Entertaining stuff! If you’re a fan of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Heroes and Monsters is a worthy companion for your bookshelf.

(America’s Best Comics, 1999-2000)

(Monkeybrain Books, 2003)