Yun Kouga’s Loveless has been a very successful manga series and a widely praised anime series, which was developed from the first four volumes of the manga. I’m warning you, whatever preconceptions you have about anime had best be jettisoned right now: this one is dense, layered, complex, edgy, and beautifully executed.

Yun Kouga’s Loveless has been a very successful manga series and a widely praised anime series, which was developed from the first four volumes of the manga. I’m warning you, whatever preconceptions you have about anime had best be jettisoned right now: this one is dense, layered, complex, edgy, and beautifully executed.

The outside “shell” story is centered on the mystery of Aoyagi Seimei’s death and the efforts of his younger brother Ritsuka to discover who was responsible. Ritsuka is twelve and remembers nothing before his tenth year. His mother is convinced that her younger son’s body is possessed by an imposter and regularly brutalizes him. Seimei was his protector and refuge; his burned body was discovered in Ritsuka’s chair in his old classroom. On his first day at his new school, he is intercepted after classes by Agatsuma Soubi, who presents himself as Seimei’s friend. Ritsuka, at Soubi’s prompting, discovers Seimei’s “will” in a locked computer file. Soubi was in reality Seimei’s Sentouki, his Fighter Unit, half of the Battle Pair for which Seimei was the Sacrifice. Seimei bequeathed Soubi to Ritsuka, to fight for him, protect him, and love him — but nothing involving Soubi seems to be that clear-cut.

The deeper story, and the story that takes up the major portion of the anime, is the growing relationship between Ritsuka and Soubi. Ritsuka, who professes not to “like” anyone and who distrusts the whole idea of love and liking, is taken aback when Soubi first professes to love him, thinking at first that he’s run afoul of some sort of pervert. That’s not Soubi’s intent, at least not for the present. Ritsuka is somewhat distrustful, and here is where we first see the tension between trust and distrust that drives Ritsuka’s side of this relationship: Soubi has, at some time in the past, lost his ears, meaning he’s a “grown-up” and his motivations are suspect. (More about the ears in a moment.)

The relationship between Soubi and Ritsuka necessarily impinges on the third strand of the narrative: Ritsuka’s return to normalcy, to the world of school friends, liking people, valuing himself (he’s very much afraid that if the “real” Ritsuka returns, he will disappear), shown most plainly in the scenes of him at school with his classmates, particularly Hawatari Yuiko, a physically precocious but slightly emotionally backward girl who promptly develops a crush on him, and Shioiri Yayoi, who initially sees him as a rival for Yuiko’s affections; and his teacher, Shinonome Hitomi, an adult of twenty-three who still has her ears and is somewhat lacking in self-assertiveness.

The context here needs some explanation. The Fighters and Sacrifices share a “true name” and form battle pairs that engage in spell battles, using words as weapons. (And how’s that for a metaphor?) The anime opens with a voice-over of Seimei telling Ritsuka his true name, which was Beloved; Ritsuka’s true name, as it turns out, is Loveless. This becomes an essential part of the main mystery, as Battle Pairs are sent by Septimal Moon, a mysterious entity implicated in Seimei’s death, to bring Ritsuka back to them — attempts thwarted by Soubi. Soubi’s strength as a fighter — and he is the strongest known, noted by his teacher, Minami Ritsu, as unbeatable — is that he has no true name, and consequently, is not bound to a particular Sacrifice.

Kouga makes use of a convention in manga and anime of depicting children (and sometimes other characters) as kemonomimi (lit. “animal ears”), that is, possessing animal ears and tails. While these are usually interpreted as cat ears, in this instance that’s not consistently the case — while Ritsuka’s ears and tail are definitely those of a cat, Yuiko’s ears and tail are very easy to read as “dog,” which fits her personality. The loss of one’s ears means that one has lost one’s virginity — hence, Soubi is a grown-up, which is part of what leads to Ritsuka’s distrust. (The rest is based squarely on Soubi’s arbitrary and unreliable behavior.)

One aspect of Loveless that is without doubt controversial, at least to Westerners, is the mere fact of the relationship between Soubi, a twenty-year-old adult, and Ritsuka, a twelve-year-old child. Kouga has said “I don’t consider it as yaoi, but my fans do.” While the manga, which is more focused on the mystery of Seimei’s death and the nature of Septimal Moon, slides past that fairly easily, the anime, focused more closely on the relationship, in fact undercuts Kouga’s contention quite specifically. Soubi says, in the first episode, “I will take you down.” Ritsuka doesn’t really know what he means, although he has his suspicions. And there is a scene later in the anime, a flashback in Episode 9, in which Soubi actually starts to take Ritsuka down when they are interrupted by yet another Battle Pair, this time sent to take Soubi out.

While it’s very hard, I think, to read the relationship itself as anything but romantic, it’s equally difficult to cast it as “predatory” or “abusive.” Ritsuka is in the throes of first love, conflicted, moody, hair-trigger, desperate to be with the object of his affection while simultaneously resenting the hold Soubi has over him. He also has much more autonomy and much more control than we in the West are willing to grant a “child” — and I set it off that way because in many ways Ritsuka is not a child. Of key importance, of course, is the character of Soubi: he characterizes the relationship as one of “master and servant” and repeatedly asks Ritsuka to command him, to order him, and to punish him, and if there is any honesty in Soubi at all, it is in that. While he has a wide independent streak, he is also under orders — first Seimei’s, to serve Ritsuka and to love him (and he confesses to himself early on that he loves Ritsuka quite aside from Seimei’s command), and then under another agenda: we also learn very soon that Ritsuka is being trained, for what and at whose command we don’t know. Soubi is, at least in part, a vehicle, and much of his own motivation is opaque.

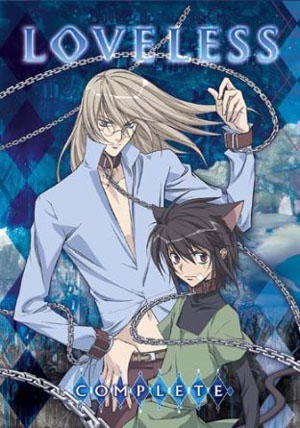

It’s a singular romance. We are presented with two terribly wounded people (and the prevalence of bandages as an image is striking) who desperately need to be connected (again, the visual symbolism is there — chains and clasped hands, both readable as a means of binding/bonding or connecting): Ritsuka has lost his big brother, his one surety; Soubi has been dominated for his entire life, first by Minami-sensei and then by Seimei — it’s all he knows. And both are fragile and vulnerable, although Ritsuka’s response when threatened is to attack. It’s instructive that the primary visual symbol for Soubi is butterflies, which he professes to hate because they are “so easily caught and pinned to a board.” In Soubi’s own mind, Ritsuka is his strength — in every battle there is a kiss exchanged, and the context is established in the first, when Soubi says “Give me your strength” and then kisses Ritsuka. Both characters are much too complex and their relationship is too multi-faceted to allow for simple summations.

One of the things I find most impressive about this anime, and a reflection of its overall high quality, is that the visual component is not only beautiful in itself, but actively reinforces the narrative — even the images shown in the opening titles reflect the symbolism I noted above. The graphics range from painterly, almost impressionistic scenes of the park and riverside, where many of the scenes between Ritsuka and Soubi take place, to the hard-edged settings of Ritsuka’s school, to the abstract and very energetic battle scenes. The style of the rendering and the scene settings resonate with the story line. Character designs are within the conventions of shoujo manga, but exceptional for that. Ritsuka is one of the cutest characters in the genre, and Soubi stands out even in a genre devoted to beautiful boys. The rest of the characterizations are in line — appealing, quirky, and highly individual — you can see personalities in their faces. The voices are also right on target — Konishi Katsuyuki as Soubi ranges from commanding to seductive to reassuring, while Minagawa Junko has got Ritsuka perfectly — he’s a twelve-year-old on the edge. The sound track is remarkably clear, and while the pacing is not always energetic, it sets up a rhythm that fits the story.

This is another case of merely scratching the surface. Viewing Loveless is a particularly rich experience, a wealth of telling details and elegantly crafted scenes — even the title songs are good. In fact, I may take the rest of the day off and watch it again.

(Anime Works/Media Blasters, 2009 [orig. Bandai Entertainment, TV Asahi (Japan), 2005])