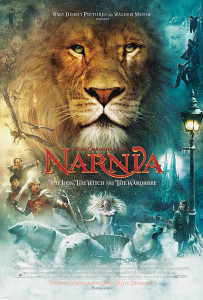

“Once a King or Queen in Narnia, always a King or Queen,” the saying goes. But as I watched Andrew Adamson’s beautifully-realized, superbly cast film of The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, I found myself wondering whether that was really true. I first read the novel upon which this film was based when I was 9 years old, when it instantly became one of my favorite books ever. It remained so for several years and through several re-readings, surpassed perhaps only by C.S. Lewis’s own The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (which has the added bonus of being set not only in Narnia but on a tall ship). Then I read The Last Battle, which I can only describe as a fall from innocence. At the end of that book, what had been vague and unrecognized Christian allegory to my young Jewish understanding suddenly became unavoidable and unpleasant. I went from relating to a Queen of Narnia to feeling as though I would forever be unwelcome in that harsh, judgmental place. Not until I read The Faerie Queene in college, which gave me an intellectual understanding of the tradition in which Lewis had been writing, was I able to try to return to Narnia again.

“Once a King or Queen in Narnia, always a King or Queen,” the saying goes. But as I watched Andrew Adamson’s beautifully-realized, superbly cast film of The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, I found myself wondering whether that was really true. I first read the novel upon which this film was based when I was 9 years old, when it instantly became one of my favorite books ever. It remained so for several years and through several re-readings, surpassed perhaps only by C.S. Lewis’s own The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (which has the added bonus of being set not only in Narnia but on a tall ship). Then I read The Last Battle, which I can only describe as a fall from innocence. At the end of that book, what had been vague and unrecognized Christian allegory to my young Jewish understanding suddenly became unavoidable and unpleasant. I went from relating to a Queen of Narnia to feeling as though I would forever be unwelcome in that harsh, judgmental place. Not until I read The Faerie Queene in college, which gave me an intellectual understanding of the tradition in which Lewis had been writing, was I able to try to return to Narnia again.

I relate this background because, for me, watching The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe is like watching three movies at once. On the purest, least complicated level, there’s a glorious children’s fantasy that my own children adore, where I readily believe in a world in which beavers can talk and gryphons ward off an invading army. Then there’s the inescapable Christian allegory that I would recognize on my own these days without having read anything else by or about Lewis: the baptism in the river, the arrival of Christmas, the godlike king who dies and is reborn for the sins of another. And finally, there’s the thorny, bramble-filled Narnia that has lived for a long time in my imagination, where I have a love-hate relationship with the great Aslan and secretly root for the sexy, powerful White Witch. I find all these Narnias in Adamson’s film, which I take to mean that the movie is brilliant: I can’t promise that all fans of Lewis will find the Narnia of their expectations, but there are certainly enough layers that those who want an innocent fantasy story will find one while those who expect a moving religious parable may experience it.

(Spoiler alert: various scenes from the movie will be discussed throughout this review.) The story begins in the midst of the horrors of World War II, where the Pevensie children are bombed out of their home and sent far away to the country to stay with an eccentric professor and his stern housekeeper. During a game of hide-and-seek, the youngest child, Lucy, hides in an old wardrobe and steps through the back into another world where she meets the faun Tumnus and inadvertently sets in motion a chain of events that will lead to a war for his homeland. When Lucy arrives, Narnia is ruled by a witch who calls herself the Queen, and when Lucy’s brother Edmund follows his little sister through the wardrobe, he falls under the spell of the sorceress, who gets him addicted to her Turkish delight and demands that he bring his siblings to meet her. Edmund does not know of the prophecy that when two Sons of Adam and two Daughters of Eve sit on the distant seaside thrones of Narnia, the White Witch’s tyrannical reign will be overthrown.

Eventually older siblings Peter and Susan find their way into Narnia with the younger Pevensies, where they discover good news and bad news: the bad news being that Edmund has inadvertently betrayed Tumnus and deliberately set off to find the so-called Queen, the good news being that the long-absent lion Aslan is on the move again. While Lucy, Peter and Susan are led by a pair of beavers to Aslan amidst signs that the hundred-year winter of Narnia is ending, Edmund discovers that the Queen is just as cruel as Lucy warned. Aslan strikes a deal with her for Edmund’s freedom, offering his own life in place of the boy’s and putting young Peter in charge of his armies. But because the ancient magic that governed the creation of Narnia forbids the slaughter of the innocent, Aslan rises from the dead and rescues hundreds of victims turned to stone by the White Witch just in time to help the Pevensies lead an army of magical beasts to victory against the Queen’s brutal forces.

After this, Narnia gets a little strange . . . well, stranger, anyway, than a place where talking horses and centaurs make up the bulk of the advance guard. Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy are declared the rulers of Narnia by popular acclaim, based on their victory and the prophecy about the evil times being over once humans ascend the four thrones in Cair Paravel. Aslan departs once more, for, as Tumnus explains, he is not a tame lion — something the children have already guessed after watching him brutally attack and kill the White Witch. For many years the Pevensie siblings reign in a kind of suspended childhood bliss, where they explore the fields and forests of Narnia, growing up to be very attractive but presumably chaste adults since they are the only humans in the land. Then one day they come across the entrance to the back of the wardrobe and fall back into the real world at precisely the moment they entered it, recovering their children’s bodies . . . and, presumably, their memories of the parents they were once so loath to leave behind.

It’s strange to look back at this fantasy from an adult perspective, wondering how someone like me could have been so infatuated with the idea of stepping through a wardrobe and ending up a Queen of Narnia. Becoming royalty is a guilty fantasy for most Americans; I once got in trouble with a friend from the Commonwealth for making jokes about Britain’s Royal Family, being informed that, as an American, I could not be expected to understand a passion for an enthroned ruler. I suppose that at 9 I didn’t fret about that, nor the question of who Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy could have dated or married, nor why adult sexuality — particularly independent female sexuality, emphasized in the film by the exotically beautiful White Witch — apparently has no place in Narnia. I accepted that Aslan was as great and good as many characters declared him to be, I feared the wolves of the witch’s secret police and I liked Susan in particular, with her bow and arrows and her refusal to let Peter order her around.

Yet even as a child I felt that Edmund was unfairly condemned for things that were out of his control; he met the White Witch almost as soon as he set foot in Narnia, when he was alone, scared and cold, and she had him addicted to her food and puffed up with promises of glory before he had any reason to see her as a villain. Worse, I always found Aslan difficult to love, even after he gave his life for Edmund’s, but particularly after he rose from the dead and admitted that he knew all along that he would; I can admire the extent to which he treats the children as adults when it comes to making decisions and sharing responsibilities, but in some ways they’re forced to grow up too fast in Narnia just as much as they were at home witnessing the horrors of war.

Most of the story arc is about how they grow up, though they still react like kids when Father Christmas arrives and when sternly lectured on doing their duty. Georgie Henley’s Lucy is particularly well-cast and well-developed; while she’s recognizably a little girl who throws tantrums and screams while chased by wolves, she is a tough little girl, unafraid to speak her mind, able to keep up with her siblings and very willing to let wonder overwhelm her fear. Really all the children are superbly cast, though Skandar Keynes’s sullen Edmund outshines his two older siblings, William Moseley’s would-be-heroic Peter and Anna Popplewell’s not-entirely-defined Susan. Though Peter is the eldest, Susan is the one who appears to be most obviously on the verge of adolescence, which will ultimately be the downfall that casts her out of Narnia in The Last Battle, when she chooses spending time with her friends over devotion to her family and what she perceives as childish fantasy; it’s hard for me to embrace Susan wholeheartedly, knowing what Lewis has in store for her.

There are some specific choices in the film that I find a bit disturbing, though one might argue that they are logical extrapolations from Lewis’ novel. Chief among them is the portrayal of the White Witch as specifically pagan: her chariot looks Roman, the mark of the invader into Britain, but the altar upon which she slays Aslan resembles Stonehenge. The White Witch is a superlative swordfighter in her own right — something I did not remember from the books, where I had the impression that she used dark magic rather than traditional martial arts — with the frost off her appearance after Narnia’s long winter ends, she reminds me a lot of Xena (I called her “Jadis, Warrior Princess” when discussing the film with my kids).

I know the White Witch is supposed to represent Satan or at least wicked ambition and surrender to temptation, but it’s really hard for me not to root for her, in large part because she’s a strong, courageous, independent woman in a land that appears to be hostile to such women. Plus she’s played by Tilda Swinton with a passion and conviction that just doesn’t come across in the CGI animal characters, though they’re voiced by such talent as Liam Neeson (Aslan), Ray Winstone (Mr. Beaver), Dawn French (Mrs. Beaver) and Rupert Everett (Fox) among others. James McAvoy, who plays Tumnus, is somewhat younger than I’d expected and rather creepy inviting Lucy home for tea; it’s a mark of how much times have changed since Lewis wrote the novel that this seems not friendly but potentially terrifying and the ease with which she agrees to go off with this stranger is equally disturbing. They develop an interesting friendship, however, which is particularly poignant once the White Witch tells Tumnus that it was his fellow prisoner Edmund who betrayed him in exchange for sweets.

Narnia is beautiful both in its frigid winter with snow on the pines and in the spring when the army masses in a caravan amidst grassy hillsides. Some of the images remind me of N.C. Wyeth’s children’s book illustrations, some look vaguely Pre-Raphaelite, some are reminiscent of previous adaptations of children’s myths like Faerie Tale Theatre’s version of “The Snow Queen.” The castle of Cair Paravel is a curious crossover of English cathedral and Ottoman architecture, while the witch’s fairy tale palace looks rather more Germanic and cold. The battle scenes may look familiar to anyone who’s seen any of the plethora of CGI battles in the past few years: they’re part Pellennor Fields from The Lord of the Rings, part battle outside Jerusalem from Kingdom of Heaven, part magical animal display from Harry Potter.

My favorite effect involves an arrow shot from a centaur’s bow that turns into a phoenix that sets a line of fire in the path of the White Witch’s army, though all the creatures are magnificently realized and it’s easy to forget that those aren’t real leopards. The wolves in particular are extraordinary — their dialogue is chilling but it’s their very reality, the fact that they move and run like real animals, that makes them so powerful, unlike the unreal CGI werewolf from Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. Not all of the effects in Narnia are quite as seamless as those in Harry Potter or The Lord of the Rings — cloaks don’t always billow when it seems as if they should, the river ice cracking patterns look orchestrated — but in this magical land, these things hardly matter.

On the level of children’s fantasy, I can’t imagine that anyone could be dissatisfied with this film of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe regardless of whether one has read and enjoyed Lewis previously. It’s a fairly faithful adaptation of the book, and if there are images or themes in the filmed version that seem familiar from Harry Potter or A Series of Unfortunate Events, I suspect it’s because Lewis has been so influential on contemporary children’s authors rather than because of any borrowing on the part of the filmmakers. I can’t really speak for how audiences looking primarily for the Christian allegory will respond to the adaptation, but it all seems fairly intact to me in the progress from the arrival of “Christmas” to Aslan’s triumphant rise.

Which leaves the question of whether a disillusioned reader like me can love The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe without bringing all that baggage into the theater. I’d have to say that my feelings are mixed; there are some decidedly guilty pleasures, like the sexiness of the witch and secretly not feeling sorry for Aslan, as well as straightforward awe at the CGI, cinematography and scenic design, and then some moments where my critical brain just won’t turn off enough for me to stay immersed in the story, like seeing the stone table used for unholy rites. I recommend The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe wholeheartedly as a film, but for readers who fell away from Lewis over issues of theology, feminism or uncomfortable racial, national and imperialistic issues that emerge in The Chronicles of Narnia, I’m not sure it will win back converts.

Michelle Erica Green

(Walt Disney Pictures and Walden Media, 2005)