Woody Guthrie was truly a legend in his own time. Nearly 40 years after his untimely death, the legend continues to grow, as does his influence on American music. Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen, to name just two popular singer-songwriters, owe their careers to the man who was the first American troubadour. And so does anyone else, male or female, who has picked up a guitar and sung about the people and places of America.

Woody Guthrie was truly a legend in his own time. Nearly 40 years after his untimely death, the legend continues to grow, as does his influence on American music. Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen, to name just two popular singer-songwriters, owe their careers to the man who was the first American troubadour. And so does anyone else, male or female, who has picked up a guitar and sung about the people and places of America.

Forests of paper have been printed with words about Woody Guthrie, and tributes recorded by the dozen. And this is not the first film that has documented his life, but it may be the most extensive. Which makes its weaknesses all the more frustrating.

This biographical documentary covers Guthrie’s life from obscure birth to drawn-out death. All but the most assiduous Guthrie scholar will learn something from it, should he or she sit through the whole thing. It hits all the high and many of the low points of Guthrie’s life and career: birth in Okemah, Oklahoma; death of older sister in accidental fire; mother’s death in an insane asylum from the effects of Huntington’s Disease (“HD”), which would eventually also claim Woody. Parapatetic childhood and adolescence in Oklahoma and Texas; learning to play fiddle and guitar; early marriage in Texas. A move to Los Angeles to be a country singer with cousin Jack; successful radio show with Lefty Lou; lots of ramblin’ and tom-cattin’. His move to New York, where he falls in with the nascent folk movement and communists; early Dust Bowl recordings for Folkways. A stint in Pacific Northwest writing songs for the Bonneville Power Administration; affair with and eventual marriage to Marjorie Mazia, a Martha Graham dancer. Shipping out in the Merchant Marine in 1941 with Cisco Houston and Jimmy Longhi; birth of daughter Cathy Ann in 1943 and her tragic death from fire at age 4; settling down in Coney Island to raise second family with Marjorie. And finally, descent into the clutches of Huntington’s, including erratic behavior and multiple hospitalizations; death in 1967.

The story is told by a succession of interviewees, particularly Guy Logsdon, Guthrie historian in Okemah, biographer Ed Cray and daughter Nora Lee Guthrie, with about a half-dozen others offering commentaries on various periods and aspects of Guthrie’s life. The whole thing is “narrated” by English folkie Billy Bragg, who stands woodenly in front of a giant record prop and reads his lines off a teleprompter. The entire film begs for a much firmer editor’s hand; director-producer Gammond should have hired someone else to edit out the many segments in which one or another talking head repeats what someone else just said.

The filming is also clumsily amateurish. While an interviewee speaks, the camera pans slowly over odd scenes and artifacts, such as the giant guitar on the Guthrie monument in Okemah. For some reason, chapters are announced by a frontal view of an antique movie projector in operation. Archival footage of cowboys or farmers is often laughably generic or even grossly inappropriate. Several times, we see two musicians playing a bluegrass version of a Guthrie song, but we’re never told what relevance they have to the story. A newspaper page blows down a path somewhere in modern Okemah — what does it signify? Background noises — phone ringing, cars honking, sirens wailing — sometimes nearly drown out the words of interview subjects.

All of which is frustrating, because some of these people are significant actors in Guthrie’s life, like son Arlo, Pete Seeger, and manager Harold Leventhal. And they have important things to say. Nora and Arlo remind us that their father wasn’t a saint at the same time that they reinforce his importance as a writer and musician. Jimmy Longhi chokes back tears as he remembers his last conversation with Guthrie days before he died. And Seeger urges us not to see Guthrie as a tragic figure: “I never think of Woody without a grin on his face,” he says. “He was basically a very cheerful guy, even though he was serious.”

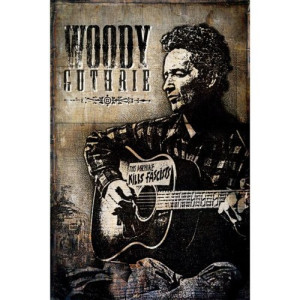

Until a more seasoned filmmaker takes on the task of documenting Guthrie’s life, This Machine Kills Fascists will have to do. In the meantime, find and read his memoir, Bound For Glory, and listen to one of the many compilations of his songs that are on the market, especially the Folkways reissue of Dust Bowl Ballads and don’t forget Bob Dylan singing “This Land is Your Land” and “Song for Woody” on his recently released No Direction Home “official bootleg.” And give thanks for Woody Guthrie.

(Snapper Music, 2005)