Craig Clarke penned this review.

Craig Clarke penned this review.

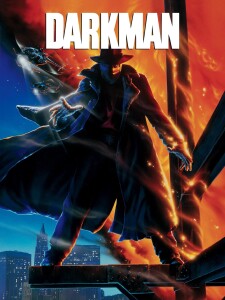

Director Sam Raimi’s first big-budget mainstream offering (after the success of the first two Evil Dead films) is arguably the best comic book superhero movie not actually based on a comic book superhero: Darkman.

Peyton Westlake (Liam Neeson) is a scientist working on a formula for synthetic skin. His girlfriend, Julie Hastings (Frances McDormand) is a lawyer who finds she is working for an villainous contractor/developer, Louis Strack (Colin Friels). When Julie mentions a paper in her possession (the mysterious “Bellisarious Memorandum”) that proves his underhanded dealings, Strack sends his henchman, Robert G. Durant (Larry Drake) to find it — in Peyton’s lab. Durant’s brutal methods lead to the first of many expensive explosions appearing in Darkman — and, of course, Peyton’s disfigurement. Peyton is thought dead when he is thrown clear of the site and ends up in the hospital — alive, but so burned his nerves have to be detached, else he would “spend the rest of his life screaming.” Afterwards, in perfect Mission: Impossible style, he uses his synthetic skin to exact revenge on the various people who wronged him by disguising himself as various members of the crew. This would be perfect if not for the added difficulty that it becomes unstable after being exposed to light for 99 minutes, bubbling and melting to humorously gruesome effect. Plus, his lack of sensory stimulation leaves him prone to violent outbursts. How’s that for a tortured hero?

But the style behind this treat is, when compared to the plot, at least as important if not more so. Anyone who saw Raimi’s early work would know that the man loves a kinetic camera. Close-ups, whip-pans, elaborate action sequences — until recently (A Simple Plan, The Gift), motion has been his stock in trade, and in Darkman, he makes it appear, in many scenes, as if a comics page had been brought to life. A particular highlight is Darkman hanging from the drop ladder of a moving helicopter as it flies throughout the city. The pilot attempts to knock him into buildings and oncoming traffic, eventually leading to another expensive explosion at a highway tunnel. Good practice, obviously, for his later work with Spider Man. Another Raimi trademark has always been dark humor (a taste shared by his friends and sometime collaborators, Joel and Ethan Coen) — how else could someone make such hilarious “horror” films? — and he makes Peyton that much more sympathetic by allowing us to laugh at his struggles. He knows that a hero is more appealing to the audience if he stumbles before his triumph.

Even so, Darkman would be nothing without solid performances to drive the characters. Neeson is marvelous in an atypical role, acting mostly with his voice as he spends most of the film either disguised, hiding his face behind myriad bandages, or in the dark. And who would have guessed that McDormand (now a “serious” actress) would be so terrific in a typical “girlfriend” role, intelligent and independent but still believably in need of rescue. (She also hasn’t been this flatteringly shot since Blood Simple.)

Drake must have relished this complete turnaround from his role playing the mentally challenged Benny on L.A. Law because he dives into Durant. Not content with just chewing the scenery, he devours entire sets. But his performance is surefooted consistency in comparison with his onscreen boss. Friels wavers between underplayed and over-the-top until the denouement at a construction site, where subtlety is jettisoned like a used diaper (which is fortunate, as subtlety has no place here). The ending plays fully to Raimi’s strengths, as his camera gets to shoot from angles usually unavailable on a normal set, not to mention the possibilities for dangerous stunts involving high falls and hot rivets.

If the film contains similarities to another secretive hero, The Shadow, it is because Darkman was originally supposed to be the screen adaptation of the character with “the power to cloud men’s minds.” However, one licensing failure and several rewrites later, Raimi emerged with a hero that is derivative yet wholly original, and a cinematic rollercoaster ride that stands up to repeated viewings — as long as one’s “suspension of disbelief” switch is kept firmly in the “on” position.

(Universal, 1990)