I was surprised when I opened my new Duke & Ella CD to find no CD inside, but a two-disc DVD set. Surprised, but not disappointed. Not disappointed at all!

I was surprised when I opened my new Duke & Ella CD to find no CD inside, but a two-disc DVD set. Surprised, but not disappointed. Not disappointed at all!

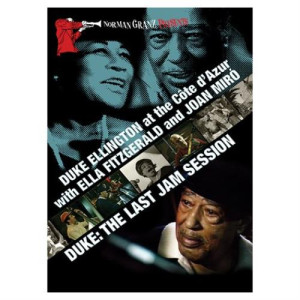

The two-disc release, Duke Ellington at the Cote d’Azur with Ella Fitzgerald and Joan Miro and Duke: The Last Jam Session opens with a fantastic introduction by Duke Ellington himself, giving a rare insightful overview of the first disc. Of spending time in the French Riviera he says: “There’s nothing like being ‘with it’ with the ‘in’ people.” He claims no objections whatsoever either to gambling (“particularly if you win”), or to a “luxuriously-appointed bikini.” He describes the forthcoming footage of Ella Fitzgerald singing with the orchestra in Paris of February 1966. Her performance showcases all the talent, consistency, and professionalism anyone familiar with the lady would expect. If she seems to be lacking the tiniest bit of concentration or exuberance; if the band seems the smallest bit conservative in their playing during her numbers; it’s no wonder. Mere hours before the performance, Ms. Fitzgerald received news of her sister’s untimely death. Watching her numbers with this foreknowledge makes all the more poignant Ms. Fitzgerald’s slightly teary rendition of Strayhorn’s melancholy and melodious “Something to Live For.”

I’m going to skip to the second disc of this two-disc set for a moment. This entire second disc is footage from the last recorded jam session over which Ellington ever presided, on January 8, 1973. Here we see the uber-cool, seventy-three-year-old Ellington dressed with his customary stylishness, eminently relaxed at his piano. The video is forgivably unpolished in quality. If anything, the unpolished aspect actually highlights the immediacy of the experience. It’s like watching home movies; as though you’re a privileged member of Duke Ellington’s inner circle. The music of the seventies doesn’t, for me at least, have the magic or vibrancy of Ellington’s 1960s (and earlier) big band performances. The informality and fluidity of spontaneous creation and synergy between the musicians is apparent, but a mere echo of the best of earlier rehearsals, most particularly that before the Antibes-Juan Les Pins Jazz Festival from the first disc.

Back to disc one: in a kind of gritty, sepia-tinted black and white, Duke Ellington’s Orchestra plays in all their sweet fullness. If you love this music, watch live footage of the stuff. Watch the facial expressions, the raw emotion, the individual responses of various members of the orchestra as they listen to their fellow musicians play. Watch Ellington pounding out on his keyboard or counting aloud to the band during such numbers as “Things Ain’t What They Used To Be” and “La Plus Belle Africaine” and the Shakespeare-inspired “Such Sweet Thunder.” All of this serves only to intensify the appreciation for this music’s complexity and virtually assures longevity in future listenings.

During the fantastic (nearly surreal) outdoor jam session filmed at the Maeght Foundation in St. Paul, Joan Miro’s sculptures fit to the music of Duke Ellington’s Trio in a synthesis of artistic fusion which is wholly midcentury, wholly Jazz. Miro, watching the band play, becomes as one of the statues himself, the planes and angles of his face in stark black and white relief under the bright Parisian sun. The sculptures surrounding the band stand like other mute observers, both as audience and as impromptu band members. There’s a power here with the addition of the visuals which isn’t fully described by the music on its own. This is what watching a live performance should convey, this sense of grander themes touched upon, which delves right into the very soul of the observer. That the power of this music, these musicians, this artwork and this footage can stretch across longer years than I have been alive to touch me in such a visceral way is rather humbling.

Ellington concludes as he opens, with the power and longevity of true genius. Only Ellington could give an entire appreciative audience (including myself, vicariously and over decades) credible instructions on how to be “conservatively hip,” how to be “respectably cool.” “One never snaps one’s fingers on the beat – it’s considered aggressive. Don’t push it. Just let it fall . . . and so . . . one discovers that one can become as cooool as one wishessss to be . . . .”

(EagleVision, 2007)