Asher Black penned this review.

Asher Black penned this review.

Given that Mists of Avalon, based on Marian Zimmer Bradley’s book by that title, aired originally as a cable television miniseries on TNT this past July, its recent release on video may be the first viewing many of us will have had. In fact, it is perhaps better viewed in one sitting than over the course of two separate evenings of television. Watching the whole thing through in one piece yields a climactic sense of depth to heroine Morgaine’s pain when late in the story she floats into Glastonbury, finds her mother’s embrace, and cries out “I’ve had such sadness!” This character knows what pain means. I know, and I heard it.

This is a revisionist Arthurian tale. The film opens much like Braveheart‘s “Historians in England will say I am a liar…” with an agonized and weary, almost crucified Morgaine narrating — “No one knows the real story. Most of what you know… is nothing but lies” — as her boat glides into the mists, a device that welded this viewer to his seat, not wanting to miss any of the necessary adjustments to the legend.

This is a story about conflict, and there is a plethora of them: Avalon versus Camelot, Christians versus Goddess-worshippers, Britons versus Saxons, oath to one’s husband versus oath to one’s deity, loving faithfulness vs. the overwhelming love of one’s heart, ends vs. means, religious purity vs. syncretism, the received version of the myth and the revised version.

This is certainly not ‘women taking over Camelot’, as one writer has put it. If there’s any better way to miss the point, I don’t know what it might be; Viviane, the Lady of the Lake, will surely visit and correct that poor soul some late lonely night. It is true that the archetypes of mother, lover, wife, crone, and goddess are prevalent here. In fact, this is the story of a Camelot seen through the eyes of its women, told as the mystery of ‘the goddess’.

What the goddess wants, says the Lady of the Lake, is a leader who can cause both Avalon and Camelot — and thus Britain — to stand against the perceived darkness of Saxon invasion, a leader to whom followers of both the God in Heaven and the Goddess of Avalon can give allegiance, “someone with the blood of Avalon” who will maintain a balanced order. The film is thoroughly religious in theme. One wishes one could say “deeply religious,” but this turns out not to be so, disappointing enthusiastic readers of the novel, if the online discussions are representative.

A primary theme in the film is a particular critique of Christianity as traditionally professed, offering in its place a syncretizing of religions. Says Igraine, “The old religion embraces yours.” Says young Morgaine, having a god and a goddess is “like having a father and a mother.” The film presents admirably the syncretist argument but offers little in the way of either a convincingly orthodox Christian counterpoint or indeed a uniquely pagan one, relying as it does mainly on stereotypes of both (blundering and inarticulate clergy, pietism, the quietism of the nunnery, no particular reason for the seasonal rites, only quaint or outrageous customs that seem to appear causelessly from nowhere).

By the end, none of the characters are particularly stalwart in their beliefs, and so the whole premise of the film teeters on sudden ambivalence. Viviane, voice of the goddess, thinks maybe her life was wasted. The goddess worshippers flock to a nunnery. Merlin dies saying “I think the goddess lives in our humanity and not anywhere else.” Lancelot suggests, “Would it not be a comfort to believe that we create our own heavens and hells.” An older Morgaine sees the goddess in a new incarnation as the Virgin Mary. Arthur reposes praying to go to the house of both deities… Clearly the filmmakers did not know what to do with a TV audience and so subjected the story to the charge which Gwenhwyfar (who Viviane rightly calls a religious “ninny”) lays to Arthur: “Neither a good Christian, nor a good pagan, nor a good husband to me.” This primary element of the film, this promising source of genuine conflict proclaimed at the beginning, eventually becomes bland enough to leave identifiable Christians and pagans alike suspecting that the real struggle lurking somewhere in the story never really comes to light in “Mists” but remains obscured in studio fog.

What saves the movie is actually the soapy inter-personal tragedy into which it descends. This is so well done that one can afford to be both disappointed at the film’s failures and thrilled by its dramatically fascinating success. The film carries an almost Shakespearean sense of folly, of doom, and twists of fate, a cursed atmosphere of Oedipal jealousy and rivalry, and sadness upon sadness. A taboo is broken that will break them all in some way. The story is about the resulting shards: the heroes and villains dying in agony; Avalon, swallowed up by a world without heroism and nothing but petty villainy. Says one character, “I thought there was nothing more that could be taken from me.” The film succeeds because, by the time its initial dilemma has been betrayed and set aside, one cares enough about the characters to want to follow them through to the end.

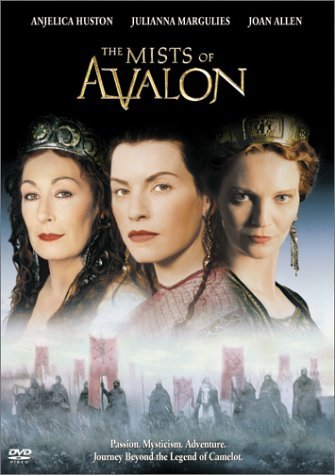

Child Morgaine, played by Tamsin Egerton (Mary Lennox in the Royal Shakespeare Company’s The Secret Garden) electrifies the set with intelligence, taking the whole story in hand until Julianna Margulies (adult Morgaine) picks it up just as perfectly from there. Morgaine drives the tale start to finish. Exquisitely strong, sensual, vibrant, and keen, she kept me in my chair the entire four hours. There’s a glow through the film, a light that moves through it, a spark of life, a vibrancy, and it’s Morgaine.

Angelica Huston makes one believe in her pragmatic Viviane. She is truly alive, as multi-dimensional as her character. Huston is the special effects of the film rather than merely relying on them to become a convincingly ethereal being.

Samantha Mathis (the diabolical, and delicious girl from Pump Up the Volume) certainly makes one hate Gwenhwyfar. She is so excruciatingly Camelot Barbie that it’s a tribute to Mathis’ brilliant acting. Sir Accolon, who keeps eyeing Morgaine from the Round Table and wants to go to Avalon, has the right idea: Who wouldn’t rather hang around with someone dark, poetic, and just plain fun? The thrillingly dangerous Vivian for that matter! Indeed, what Lancelot sees in Gwenhwyfar is never quite clear. But Gwen’s bombshell-queen-in-her-tower female character isn’t an entirely flat villain. She’s also a tragic figure, admitting the reality of completely true love while affirming the inordinancy of fulfilling it: “There will be nothing between us, will there, my love?” And so one comes to care about her as well.

On the whole, the women are magnificently acted. It’s clear that more emphasis has been placed on female casting for the obvious reason that the heart of the story is its women. The only truly brilliant male is Accolon (Ian Duncan). One senses quite clearly his bursting desire to taste something feral like a ripe fruit. On the other hand, the Merlin of Britain is just too emotionally feeble as a priest of the Goddess and Lancelot (Micheal Vartan) comes off not even as dashing and devoted but merely smitten. Still, each of them are allowed a single brilliant moment of dialogue.

For Merlin, it is his tender dying words, given to a hopeless and grieving Vivian who asks if it was all for nothing: “No. We didn’t fail. We did what we thought was right every single moment. Sometimes we were headstrong. But we lived our lives with passion and commitment. We must find a moment of happiness – a single moment we can call our own.”

For Lancelot, it is his last words to departing Gwenhwyfar, “I pray there is a heaven, and that you would be an angel in it, so when I die we can be together at last.”

Hans Matheson’s portrayal of Mordred is intolerably shallow and more fitting to a Krull sequel than an epic Arthurian romance. Fortunately we have little enough of him. His wide-eyed roaring for blood vengeance only succeeds in making him look like someone who has never really thirsted for blood. He comes off not like a believable Mordred but like a poor yet reasonably comfortable young actor trying to be Mordred. The typically overplayed insanity covers an otherwise flat and merely banal evil. Uther (Mark Lewis Jones) is certainly better but comes off like a seedy biker in a cut-off vest who really needs to have Steppenwolf do his theme song.

The clothing is luscious. One is likely to covet several of the pieces modelled in this visual catalog of fantasy regalia. The armor is perhaps the only exception – a bit too light and pretty to offer much protection, and of course who wants to dress like a Saxon? Furs are out!

The battle is adequate. Elements of it are even truer to period and setting than one often gets in a fantasy film. The confusion of the battlefield, the diminished visibility, the hamstringing of horses (faked, of course), and the reasonably small number of combatants are refreshing for their realism.

The music of Loreena MacKennitt from her album Mask and Mirror while predictable is perfectly arcane and succeeds in setting a haunting, living undertone much like the mists at one’s feet on the holy isle.

One visually stunning scene that needs mention is the preparation for the ritual lovemaking at the Beltane feast. Morgaine’s body paint as Virgin Huntress is unbearably erotic. The music, camera work, and various sensory devices truly do produce the atmosphere of a compelling recapitulated fertility. Its only awkward moment is when the boy hunter finally shows up — awkward because he truly is a boy coupled with a grown woman, but for reasons the film will make abundantly clear. Then for all the trappings, the lovemaking is decidedly subdued. A connoisseur of believable sex scenes will not be too disappointed, though, if one accepts that the loss of virginity in this case is ritual and magical and must be viewed through the lens of the surreal.

(TNT, 2001)

[