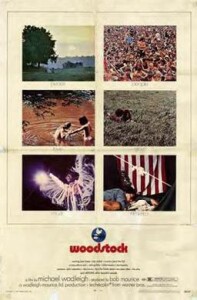

What started as a three-day music and art festival in the farmlands of upstate New York in July 1969 became one of the touchstones of a generation and an era. This 25th Anniversary “director’s cut” edition of the movie that documented the phenomenon that was Woodstock captures the event in all its sprawling chaos and unlikelihood.

What started as a three-day music and art festival in the farmlands of upstate New York in July 1969 became one of the touchstones of a generation and an era. This 25th Anniversary “director’s cut” edition of the movie that documented the phenomenon that was Woodstock captures the event in all its sprawling chaos and unlikelihood.

What this film also captures is the beginning of the end of rock as roots music, before it descended into the mass-produced corporate arena rock that this festival helped to spawn. Woodstock showed that the music could unite a generation, seemingly only moments before that music splintered into the multitude of genres of today, from pop to rap to punk to metal, that reinforce our differences rather than bringing us together.

Watching Woodstock today, one is struck by how much of the music was folk music, or based on blues, gospel, doo-wop and other roots forms. Just look at the list of performers: Crosby, Stills & Nash with their sunny three-part harmonies; the blues purists Canned Heat; bluesy folkster Richie Havens, one of the architects of World music; Joan Baez, belting out the blue-collar anthem “Joe Hill” in her quasi-operatic soprano; acid-folkies Country Joe and the Fish and Jefferson Airplane; singer-songwriters Arlo Guthrie and John Sebastian; blues belter Janis Joplin; Santana with their rock-infused Latino beats; Joe Cocker when he was still a great white soul singer; and the acid-drenched blues of Ten Years After and the great Jimi Hendrix.

Sure, not everyone fits the folk-rock or roots label. There’s The Who with “We’re Not Gonna Take It” from their rock opera Tommy, one of the works that opened the door to the pretensions of art rock of the ’70s and ’80s. But they also turned in a blistering performance of that early rock ‘n’ roll hit “Summertime Blues.” We’re spared the proto-metal of Mountain, but not the cheerfully anachronistic Sha Na Na, who were there at the insistence of Hendrix and went on to host a popular TV show.

The theatrical release was a critical and popular success. It received an Oscar in 1970 for Best Documentary Feature, as well as nominations for editing and sound. This “director’s cut” version, which included a brief theatrical release and home video, with an additional 30 minutes of footage, clocks in at 219 minutes or about three-and-a-half hours. At times it seems as though it’s going to last as long as the festival itself did. There’s a lot of footage of the stages being built, and long-haired flower children practicing yoga and bathing in streams, and way too many interviews with spaced-out festivalgoers. There are also illuminating moments, such as the cheerful middle-aged fellow pumping out and cleaning the portable toilets, who says he has one son attending Woodstock and another piloting helicopters in Vietnam, before moving on to the next toilet.

The film also reminds us that not every young person then was a hippy. A good many of those attending were, in fact, ordinary students or working-class youths bent on having a good time, making noise with their motorcycles, and scoring some free sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll.

The music runs the gamut from banal to brilliant. Alvin Lee’s guitar and vocal histrionics on Ten Years After’s “I’m Going Home” may have seemed daring and innovative at the time, but now seems self-indulgent. Santana’s “Soul Sacrifice” remains one of the most electrifying performances of the era. A seriously inebriated Janis Joplin’s over-the-top “Work Me, Lord” contains all that was good and bad about this Texas bad-girl’s art.

The end of the ’60s was a self-indulgent time in America, and this film reflects and at times seems to revel in that self-indulgence. When it does, it remains a relic of the era and its excesses. When it focuses on the music and the musicians and the humanity of the audience, the young people willing to put up with incredible discomfort for the sake of this music that defined their generation, it nears the realm of art. In either case, it’s an important statement and a valuable document. More often than not, it’s also a lot of fun to watch and listen to.

(Warner Home Video, 1994)