Asher Black wrote this review.

Asher Black wrote this review.

Hush little baby, don’t say a word

And never mind that noise you heard

It’s just the beast under your bed,

In your closet, in your head.

– Metallica

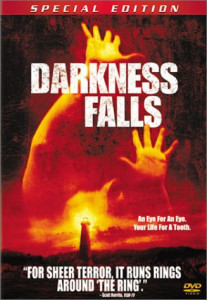

Look under the bed, check the closet, put Duracells in that Mag-Lite, and make sure all the windows are locked. Sound advice for when you come home from that late night showing of Darkness Falls. And don’t even think about inviting a dark fey into your room by putting a tooth under your pillow, let alone peeking when she comes. If you see her, she won’t forget.

In this tale, the tooth fairy is not a benign sidhe at all. Nor a harmless one. The only escape from her is into the light, and light (in this world) is always temporary. Yes, the retelling of fairy tales, or perhaps their rediscovering, has caught up with filmmaking at last.

It’s about freaking time!

I’ve been waiting for a film like Darkness Falls ever since “Shadow Man”, a 1985 episode of The Twilight Zone. You know how sometimes a child will insist that something lives under the bed. In that episode, the apparition is the child’s protector, the shadowman. He has one rule. He cannot harm the one under whose bed he lives. The boy directs the shadowman to scare away the school bullies, until at last he too becomes a bully. In the final scene, the child stands triumphantly over his fleeing foes, but wonders why the shadowman is turning upon him. “You’re the shadowman. You can’t harm the one under whose bed you live!” cries the child. “Yes,” replies the shadowman, “but I’m not your shadowman.”

Nothing quite so creepy has lurked in the night until now.

For a couple of decades, it’s been considered un-tough for horror films to rely on the “merely” primal terrors, humanity’s ancient struggle with the dark, that singular element that reflects nothing back except the void in our own souls, that wholly other. Instead, we’ve had film after film relying on the purely urban fears of a particular social class in a particular part of the world. Occult child prodigies, stalker flicks, chainsaw massacres, evil stepfathers, serial killers, descents into creative depravity (like The Cell) and monster movies that rely on an ever-increasing slough of gore, have been the mainstay.

Not that films like Alien or The Shining weren’t extraodinary. Phantasm, for all its camp, will certainly leave one sleepless in Seattle. Flatliners gave us a taste of that fear of death not as annihilation but as believable waking damnation – the retribution of those against whom we’ve sinned, hot upon our trail. And postmodern horror like The Cube is certainly a shocking assault upon one’s equilibrium.

But lately, especially, the old nightmares of the cave have come howling and snuffling back across the threshold. A return to the high terror of the old fairy tales, stories that stood as a warning that perhaps we don’t know everything, and perhaps we sleep better for it.

The Mothman Prophesies (urban legend at its finest) brought back the film noir use of shadows, moving vegetation, implied danger off to one side, somewhere off camera. The fact that we couldn’t get a good look at it was part of the terrifying fascination. Shyamalan gave us a nice brew of rustling life under the night sky in Signs (more urban legend), even if it did drown us with an ending too predictable to be predicted. Remember the little girl’s line? “There’s a monster in my room.” A warning as to what goes on when we surrender to sleep.

Then Wes Craven hit home with They, a film similar to this one, giving adults a sense of that frightful dark, the presence in the closet, the hand reaching up from under the bed.

In theme as well as technique, there’s a new sense of minimalism in the air. Instead of splattering the camera with brains, we’re being met with more suggestion, less gratuitous waste and glamourisation of special effects. The rudimentary horrors of daily existence are upon us again.

What I like so much about Darkness Falls, as well as Craven’s They, is that besides that light and deft touch, you can really feel with the film what it was like to be afraid as a child. Both films, especially this one, rely on suspension of jaded adult comfort with an ordinary good night’s sleep. That sense that the worst thing lurking in the shadows of suburbia is a conventional axe-wielding psychopath, escaped from the local asylum, is being challenged again.

We’re back to the basics of human fear.

We haven’t forgotten that it’s debilitating fear, and that our earliest encounter with media told us “there is nothing to fear but fear itself” even as it now prods us to fear whatever we are told to fear. Perhaps that’s why horror on film is moving away from the canned fears and packaged terrors of the nightly news, and asking us to remember simpler, more reasonable ones.

In fact, the film is something of a social commentary on the limits of treating that other kind of fear as madness: over and over we hear the diagnosis of “night terrors.” We even see something of the fear displayed by traditional medicine, with its technological approach to the human mind, that there might be something in the night of which to be terrified, as they deal with the notion by putting a terrified child into a dark sensory deprivation chamber – something from the rubric of vivisection and human experimentation – something of that other kind of madness of which only the sane can be afraid.

And there is at the root of fear, the film tells us, human despair. As a child says, “Sometimes I think of turning off all the lights and letting her come and take me. Sometimes I think that would be easier than being scared.” Perhaps it would be easier to surrender to what haunts us, helpless as we may be against it, and maybe we make and watch films like this one because we’ve wrestled with that somewhere in the night of the soul.

Now, this film may reawaken that old fear of things that go bump in the night, so here’s a word from personal experience. When I was a child, I didn’t stop being afraid of the dark by deciding there was nothing there. I stopped being afraid by learning to welcome the dark, and deciding that whatever is there has as much to fear from me as I do from it. Perhaps that’s a better solution than trying always to live in the light, only to find that the lights can flicker out when we least expect it.

The film’s official Web site is here.

(Columbia, 2003)