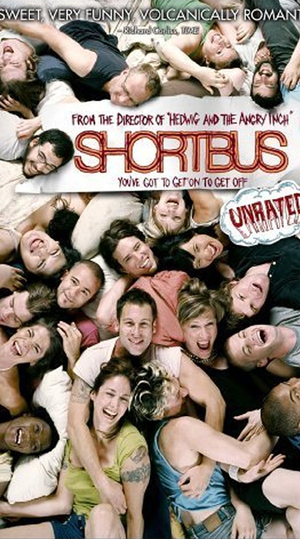

Shortbus is one of those films that comes apart if you try to look at it element by element. There’s not much of a plot, which we should all be used to by now. The characterizations are not startling for their depth: the people being portrayed are not much different than the rest of us, not particularly deep, not remarkably shallow, just awkward, charming, vulnerable, stubborn, funny and dumb. I will say, however, that they are right on target. The cinematography is apt and the score is perfectly suited. In fact, it’s one of those works for which the term “seamless” seems perfectly appropriate.

Shortbus is one of those films that comes apart if you try to look at it element by element. There’s not much of a plot, which we should all be used to by now. The characterizations are not startling for their depth: the people being portrayed are not much different than the rest of us, not particularly deep, not remarkably shallow, just awkward, charming, vulnerable, stubborn, funny and dumb. I will say, however, that they are right on target. The cinematography is apt and the score is perfectly suited. In fact, it’s one of those works for which the term “seamless” seems perfectly appropriate.

Director John Cameron Mitchell, the guiding force behind Hedwig and the Angry Inch, says “Sex is really just another language with which we try to connect, and the film is about connection.” Interestingly enough, Neil Bartlett’s narrator in Ready To Catch Him Should He Fall remarks of Boy and O, “Talking is not how they found out about each other,” marking one of many resonances between Mitchell’s film and Bartlett’s book.

Both are set in particular times and places, Shortbus in post-9/11 Manhattan, Ready To Catch Him in London before the repeal of laws criminalizing homosexual behavior. In both cases, we are talking about a time when fear was (or is) a constant undercurrent.

The opening sequence of Shortbus takes us from the Statue of Liberty across a cartoon miniature of Manhattan to two craters in the ground. We then discover James (Paul Dawson) in the bath with his ever present video camera, filming his genitals. He follows this with a focused and determined session of autofellatio, recorded not only by his camera but by Caleb (Peter Stickles), who lives across the street from James and his lover Jamie (PJ DeBoy). This sequence is intercut with scenes of wild, creative and highly acrobatic sex between Sophia (Sook-Yin Lee), a couples counselor, and her husband Rob (Raphael Barker).

“Shortbus” is the name of a bar/salon/lonely hearts club, one of those places where you have to know someone to get it. Jamie and James are regulars and vouch for Sophia and Rob after their first counseling session. It’s a Place, one of those not entirely in this world, where one finds a heady mix of art, music, intense discussions, confessionals, and unrestrained carnality. There we also meet Ceth-with-a-C (Jay Brannon), an enormously appealing young man who confesses himself totally in love with Jamie and James (as a couple, not as individuals), and Severin (Lindsay Beamish), an artist who makes her living as a dominatrix and who herself has relationship issues. And, as we learn fairly soon, Sophia is in search of The Orgasm, never having had one (she fakes them for Rob), while James has never allowed himself to be penetrated.

It’s hard to know whether these people are running toward something or away from it. I think the post-9/11 context can be read as symbolic as much as concrete, a sort of pointer to the real unease. The film is about the fear of connecting as much as it is about the need to connect, fear of everything that will allow us to make those necessary connections: intimacy, acceptance, freedom, openness, trust, surrender, the whole complex of emotions that are necessary for love but that also stand in its way. Toward the end of the movie we see Rob, back with Sophia at Shortbus after a session with Severin involving verbal abuse and a cat-o’-nine-tails, sitting there gazing at his wife with, for the first time, a peaceful look around the eyes, along with a Mona Lisa smile, having discovered, I think, another part of the definition of who he is. (He has, not surprisingly, some masculinity issues stemming from being under-/unemployed.)

This is a highly satirical film, although the satire is in the subtext. A scene in which Rob and Sophia face each other trading affirmations after an argument is a deliciously ironic put-down of pop psych and political correctness, played straight. Shortbus itself, the club, with all its glam tackiness (beautifully personified in its proprietor, Justin Bond, who plays himself), subverts the sense of all the high seriousness with which we endow “interpersonal relationships” (at least when we spend too much time thinking and talking about them, which is just another way of keeping our distance). It also provides the most obvious link to Bartlett’s novel, much of which takes place in The Bar, another venue for high drama and seduction.

Of course, if you’ve heard anything about this movie at all, you’ve heard that it has Real Sex. Yes, it does. Lots of it. Sex is the vehicle for everything that’s going on here. And Mitchell and the cast manage it all — masturbation, autofellatio, voyeurism, one-on-one, a three-way, and a couple of orgies, gay, straight and nondenominational — without ever getting close to pornography. Like the song-and-dance numbers in a good musical, as one commentator noted, it moves the story along, provides context and development. Filmmakers (and just about anyone else) tend to treat sex like the numbers in a bad musical: everything grinds to a halt for The Sex Scene. The three-way, looked at objectively, is easily outrageous enough to have been conceived by John Waters, but it is so natural and flows so effortlessly from the story that you realize you were laughing that hard only because the characters were. In a very real sense, the film’s tagline is absolutely true: “Voyeurism is participation.” It all makes Shortbus one of the most subversive works I’ve seen in any medium.

Although there are places where it loses focus, I can’t do anything but give this film the highest recommendation. For something this engaging and intelligent, I’m not going to sit here parsing parts. Where else are you going to find sex, psychodrama, and a happy ending, complete with marching band?

(ThinkFilm, 2006) Full credits at IMDb.