Rachel Manija Brown wrote this review.

Rachel Manija Brown wrote this review.

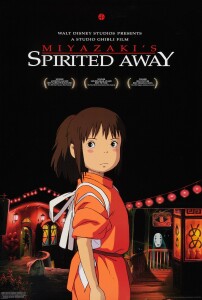

I saw this movie at the El Capitan theatre in Hollywood. A Democratic fundraiser was going on across the street, and there were about six people protesting. A young man with a pink Mohawk, dressed in a kilt, was playing the “Star Wars” theme on bagpipes. (I’m not sure if he was there in support of the Democrats, support of the protesters, or just because he felt like dressing in a kilt and playing the Star Wars theme on bagpipes on Hollywood Boulevard). It was the perfect atmosphere in which to see the surreally funny Spirited Away.

The film begins with a classic fantasy device. Timid young Chihiro’s family is moving, much to her dismay. As they drive over bumpy roads to their new home, they come across a strange tunnel. Chihiro doesn’t want to go through, but her parents insist. It’s a portal into a bizarre land of spirits, gods, and creatures, which her father mistakes for an abandoned theme park. Her parents promptly do the worst possible thing upon making such a transition into fairyland: they start gobbling food from an abandoned stall. In an echo of Odysseus’ men on Circe’s island, they are transformed into pigs; in an echo of Persephone and the pomegranate seeds, Chihiro must eat a single red seed or fade away into nothing.

She ends up working at a bath house for tired and dirty spirits and gods, populated by the wildest assortment of mythical creatures since The Encyclopedia of Fairies. The Radish Spirit is just the beginning. There’s also a horde of adorable soot sprites, even cuter than the ones in My Neighbor Totoro; frogs in kimonos; three bouncing green heads, who are apparently the pets of the formidable owner of the bath house; a magnificent furry dragon; and a chubby rat who is the subject of a series of howlingly funny sight-and-sound gags. Every single one of them has a distinct personality, even the slightly damaged origami bird.

Hidden identities are the rule of the day. Not since Diana Wynne Jones’s Howl’s Moving Castle (under option, appropriately enough, by Miyazaki) have so many characters under one roof been imposters, under identity-warping spells, using names that are not their own, wearing masks, shape shifters, or otherwise not as they seem. Chihiro’s name is magically changed and, in a nod to every name-magic fantasy from Rumplestiltskin to A Wizard of Earthsea, she can’t leave until she gets her real name back.

This is a film in which a helpless and helpful spirit may turn out to be a devouring monster, and a devouring monster may turn out to be a lonely, hungry spirit. One of the funniest sequences, a piling up of gross-out upon gross-out, eventually turns upon a moving revelation in which healing reveals both the cause of the illness and the true self. As in most Miyazaki films there are no real villains here, only characters whose greed or other flaws sometimes mask, if not always a heart of gold, at least an honorable willingness to stick to a bargain. The tone of the film is captured in a sequence in which Chihiro spots an eerie faceless spirit during a storm … and invites it inside so it won’t get wet.

Visually, it’s an exquisitely detailed, painterly film. Miyazaki’s incomparable style encompasses everything from comedy to pathos, from heartbreakingly beautiful vistas to sequences of Hitchcockian suspense, from the very Japanese mask of the No-Face spirit to a lamp post that might have stepped out of a Disney version of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. A number of images, like a train running on the surface of the ocean, are pure magic.

What am I saying? The entire movie is magic.

(Studio Ghibli, 2002)

For more about the magic of Hayao Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli, see our review of

My Neighbor Totoro, Kiki’s Delivery Service, and Princess Mononoke.