Rachel Manija Brown wrote this review.

Rachel Manija Brown wrote this review.

It takes less than a second for a person’s life to hit free-fall, the point at which death is imminent and inevitable. A dropped CD distracting you from the freeway ahead, a step forward onto rotten ice, a jab with a contaminated needle. In an instant, you’ve gone to another place and there’s no coming back. You’re still breathing, thinking, opening your mouth to shout for help, but you’re dead. And you know it.

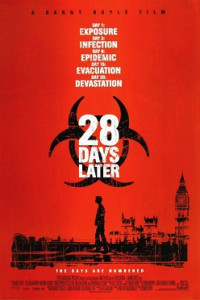

Most horror films play on the fear that something terrible is about to happen. 28 Days Later is about the realization that the worst has already happened. It emphasizes the loneliness and shock of such a moment as much as it does the terror of knowing one’s own doom.

In a nerve-wracking prologue, animal rights activists break into a lab to free sad-eyed chimpanzees that are being forced to watch scenes of human violence. A technician warns them that the chimps are infected with “rage,” but the activists, filled with their own righteous anger, ignore him. One of the monkeys leaps …

28 days later, a man wakes up from a coma. The hospital is deserted. The city outside is deserted. The awakened man, Jim (Cillian Murphy), is skeleton key thin, with huge spectral eyes and a translucent complexion, as if he evolved underground hundreds of years after the apocalypse. He wanders London like a ghost. These scenes, shot in grainy digital video, are suffused with a haunting and eerie beauty.

Jim soon discovers that England is not as deserted as it looks. The rage virus causes its victims to revert to a mindlessly savage state, running around projectile vomiting blood and looking for people to kill. If their blood or saliva gets into an uninfected person’s bloodstream or mucous membranes, they have about twenty seconds before they become infected too. Which is how long the unfortunate victim’s companions have to kill him before he turns on them. And how long the victim has to realize his own plight.

Despite this, the survivors Jim meets up with are not as hardened a bunch as one might expect. There’s a sad young man, and a father and daughter who have decorated their locked-down apartment with strings of Christmas tree lights and are still trying to keep their goldfish alive. Even Selena (Naomie Harris), a young black woman who is hell-bent on surviving at any cost, is willing to accompany Jim to look for his family. Or, as she puts it, “Sure, let’s go see your dead parents.”

The survivors’ odyssey across England is one of unrelenting tension shot through with moments of irony and tenderness. All the performances are good, but the father-daughter relationship between Brendan Gleeson’s jovial taxi driver and his teenage daughter (Megan Burns) is particularly moving and realistic.

The unpretentious script, the use of believable and unfamiliar actors rather than recognizable stars, and the use of digital video rather than film give the movie a sense of realism which makes it scary as hell.

It’s not technically a zombie movie, for the infected are still alive, but it uses the conventions of one to great effect. The infected only come out at night, and any of the characters can, in the blink of an eye, become one of them. Like zombies, the infected are figures of fear and pathos, symbols of death and worse than death. But unlike traditional zombies, they move with terrifying speed. And they are motivated not by cannibalistic hunger, but by animalistic fury.

As the third act predictably but effectively drives home, the line between virus-induced and event-induced rage may be a fine one. In a movie with homages to almost every post-apocalypse and zombie movie ever made, this may be a nod to Forbidden Planet‘s Monsters of the Id. Or perhaps it’s a point which seems obvious because we all secretly fear that it’s true.

There are some logic issues — why are the streets so free of cars, where are all the bodies, why do the survivors stop wearing protective gear, and (most egregiously) why does Jim once go inside a dark building for no reason whatsoever — but overall the film works beautifully as a spooky parable of rage, hope, and loneliness.

The film is rated R for “many scenes of maiming, dismemberment, clubbing, shooting, bayoneting and shoplifting.” I include this for its insight into the moronic worldview of the MPAA. The “shoplifting” occurs after the end of the world. The owners of the shop are presumably either dead or zombified, and the “shoplifters” would not only starve without taking whatever food they can find, but, in a bit of gallows humor, actually pay for it. All the same, don’t bring the kids.

(Fox Searchlight, 2002)