Kimberlee Rettberg penned this review.

Kimberlee Rettberg penned this review.

Almost every high school student is familiar with Beowulf. It is, after all, the first known written epic in the English language. And through better and more modern translations appearing every year, the poetry’s timeless beauty is even more accessible than it ever was. It should be little surprise that, in this flush of recent accessibility, someone in Hollywood should choose to make Beowulf into a film–a science fiction film, at that. I’ve got to say, it’s a fascinating idea. But it takes a great deal of nerve to tackle such an ambitious project–as well as heaps of creativity and sensitivity. You won’t find any of that in this 1999 version of Beowulf.

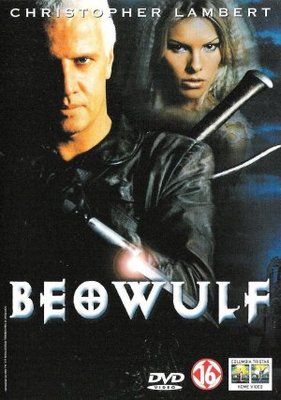

The film, starring Christopher Lambert, of The Highlander fame, does little more than give lip service to the original epic. Even if a viewer had absolutely no foreknowledge of this great work and judged the film solely on its own merit as a science fiction piece, the film falls flat on its face. The storyline barely resembles the original Beowulf, outside of a few common characters, and a couple of monsters. But, after all, some change is inevitable: the whole genre of the material is being changed. What is unforgivable is the poor acting, the forced relationships between the characters, and the tacky use of barely-clad babes to keep viewers’ interest.

The essential storyline of epic poem is a marvel of simplicity: brave warrior goes to foreign king to rid him of his rampant monster; succeeds only to face the beast’s dam in a lake; heroically slays both monsters to save King Hrothgar’s court. Heaped with honors, warrior returns home a hero, and eventual king. He rules justly for fifty years; then, in his old age, one last foe threatens him: a dragon of a deep cave. Knowing in his heart that this will be his last battle–and his own mortality–King Beowulf bravely faces death (and takes the dragon down with him).

Beowulf, the film, goes something like this: scantily-clad princess is saved from the guillotine of the mobs by a stranger on horseback named Beowulf. They proceed on to the castle, where desperate King Hrothgar tells Beowulf about their problem. The problem, of course, is that a monster, Grendel, has been haunting the castle after dark and making late-night munchies of the king’s court. Hrothgar has tried to face the monster himself, but the beast refuses to fight him. The entire court is under the suspicion that Beowulf is really there to avenge the death of Princess Kyra’s murdered husband, but agrees to let him in to fight the monster. In the ensuing battle, Beowulf receives mortal wounds–but to everyone’s surprise, they mysteriously vanish by morning. Beowulf confides to Princess Kyra that he isn’t any more human than Grendel is–he is the son of Beo, a god of evil–the only difference between them being that Beowulf escapes from being evil himself by fighting it wherever he goes. This information not withstanding, Beowulf enters into a lifeless tryst with the princess.

Roland, the best of the king’s warriors, is jealous of Beowulf because he himself is in love with Kyra–who only sees him as a brother. Beowulf does indeed mortally wound Grendel, and hangs the bloody claw from the rafters in the mead-hall where the celebration ensues. At least I think they’re celebrating (with this cast, it’s mighty hard to tell). However, the celebration is short-lived. Right afterward, we see the mysterious tart we’ve been cringing at in King Hrothgar’s lusty dreams–now at the castle gate–seducing Roland into letting her inside by letting her–well, never mind. Arriving triumphantly at the mead-hall, the blonde holds forth by announcing that she is Grendel’s mother. It is she who caused the late queen to commit suicide by jumping from the battlements, after taunting the good queen with her pregnancy. She then lays a big old whammy on King Hrothgar, claiming that, through their past affair, Grendel is really the king’s son (hence the lusty dreams). Cursed out and spurned again by the king, Grendel’s mommy commences to morph into what looks like a Transformer toy and fly around the mead-hall, conveniently killing everyone but Beowulf and Princess Kyra. Beyond this, it really becomes too painful to watch. But there is more–though the rest of the film is so dull it makes the first half shine like Christmas morning.

Christopher Lambert, in the title role, may as well be a cardboard cutout, flatly growling out confusing epigrams and occasional curt attempts at wit. Beowulf the warrior he may resemble, but without the cool weapons and Jackie Chan moves, still a poor one. Did I say Jackie Chan? In Beowulf? Yep–in fact, not only Beowulf, but most of the cast, seem to be black belts in the martial arts. Even when it’s totally unnecessary, Lambert somersaults and flips through the air like a flapjack. But much harder to watch is his feeble attempt at romance. For King Hrothgar’s foxy daughter, it must have been like making out with a lamppost. Rhona Mitra breathes a little fire into her role as the saucy princess, but not enough to rescue the film. The other players are adequate at best. But worst of all is the character acting of Grendel’s mother. Who on earth would expect the monster’s dam to look like a silicon-puffed Playboy cast-off? As she licks her lips and seduces the castle’s menfolk–including Hrothgar–her performance is almost laughable. What am I saying? It is laughable. Her outfits definitely nail the Worst Costume of the Film award, especially in her final scene–but I’ll leave that, er, to the imagination. Never mind that there were no babes–bodacious or otherwise–in the original Beowulf, except for Hrothgar’s queen–least of all one dressed in a seaweed Wonder Bra.

There are other things that bother me. Like the attempt to entangle Beowulf, Roland, and Kyra, in a romantic triangle with about as much chemistry as a puddle of mud. Grendel’s mother and King Hrothgar, seen only in confusing segues, are downright embarrassing. Oh, and there is also the interjection of a foil of sorts into the muddle: a likable, but very out-of-place weapons manager named Will. Placed among the drab and humorless castle-folk, the character of Will is a very modern-day, hip black kid who seems as though he were spliced in at random from another film.

Okay, there are some really cool weapons in Beowulf. A couple of neat visuals and gimmicks, too, like Hrothgar’s castle: its main tower consists of a giant fist opening and closing. Let’s see, what else is good–well, Beowulf rides a beautiful black horse. Aside from a few widely scattered goodies, the film makes a huge disappointment out of what could have been a great idea. But the biggest tragedy of all lies in the essential fact that, for all his bravery and victories, in the epic poem Beowulf deeply realizes his own humanity. He is a true hero, while the film’s Beowulf has no humanity at all–heck, he isn’t even human to begin with! Makes him mighty hard to relate to.

Lovers of great literature, beware: this film tramples ruthlessly on sacred ground.

(Mirimax, 1999)