I have a confession to make: I’ve become addicted to the BBC nature series on Netflix. It’s probably the natural result of a boyhood spent poking around in the empty lots and forest preserves around my childhood home, seeing what was there to see, aided and abetted by a father who encouraged my curiosity.

I have a confession to make: I’ve become addicted to the BBC nature series on Netflix. It’s probably the natural result of a boyhood spent poking around in the empty lots and forest preserves around my childhood home, seeing what was there to see, aided and abetted by a father who encouraged my curiosity.

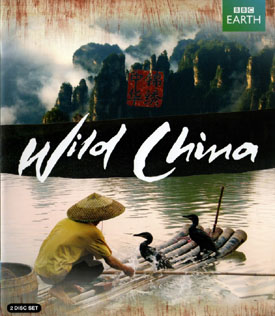

One of the better series from BBC is Wild China, which examines not only the wildlife of a vast and highly variable country, but also the geography, geology, and the attitudes of the human populations. The six episodes give a geographic survey, starting in China’s south and southwest, in the “fairy tale hills” of Guilin and the hidden valleys of what Westerners know as Shangri-la, moving up to the Tibetan Plateau, then along the Great Wall and beyond, with segments on the Mongolian steppes and some pretty formidable deserts, and finally around to the central plain and China’s 14,000 kilometer Pacific Coast.

As is usually the case, there are segments on the various animals who inhabit these various regions – red pandas and golden snub-nosed monkeys in the southwest, along with the last remaining herds of wild elephants in China; pikas, Tibetan brown bears, chira antelopes and wild yaks in Tibet (and snow leopards, of course, in the Himalayas); wild horses and Siberian tigers in Mongolia; giant pandas in south central China; and the many varieties of migratory birds (including cranes, which the Chinese have revered for centuries) and the coral reef environments along the coast.

Two aspects of this series I found particularly rewarding. First, the series quite cogently relates the geography and geology of the land to the wild creatures and people who live there. For instance, in the karst landscape of the far south, we get to examine the extensive caves, a result of the erosion of the limestone bedrock by rain water, with a segment on the Francois’ langurs, who are not only at home in the trees but are expert rock climbers who retreat to the caves for shelter at night. And those golden snub-nosed monkeys in the hidden valleys of Shangri-la, living high up in the Hengduan Mountains, manage to cope with temperatures of minus 40 degrees. And did you know that the Tibetan plateau drives the monsoon? Yes, it’s bitterly cold in the winter, but in summer it acts like a hotplate, and the rising air pulls in the moist air from the Indian Ocean, which runs into the mountains and, voila! Rain. Lots and lots of rain.

The second thing I found striking is that the series doesn’t ignore the people. The people of China comprise somewhere in the neighborhood of fifty ethnic groups, and they all seem to share a reverence, and in some cases a working relationship with nature and its creatures — one of the opening sequences shows a group of fisherman out early in the morning with their tame cormorants, who do the actual fishing. (That’s just one illustration of how the people of China make use of natural resources; there’s also a sequence showing two men “tagging” a wasp with a bit of feather and then following it back to the nest, where they smoke the inhabitants out and feast on the grubs, which are considered a delicacy.) The Dai people of the southwest consider their native forest sacred and structure their kitchen gardens along the lines of the rain forest. In Tibet, we see not only a bear hunting pikas (the fox tagging along was more successful), but a major Buddhist festival and the people of one village caring for a wounded crane. In Mongolia, there are horse races and hunting with a golden eagle, and a reserve set aside for the last remaining wild horses. In central China, we see an example of the grassroots attitude toward conservation in a sequence showing a man who has taken it upon himself to care for a Chinese alligator, the “muddy dragon” that is almost extinct in the wild. And along the coast, we see a poacher-turned-conservationist trapping shore birds so they can be banded, measured, and released to be tracked in the future. And in the Yangtze estuary, we see Pacific white dolphins that have adapted to the constant noise of passing boats and barges by compressing their own clicks and whistles to contain more information in a shorter time.

And we see the results of the Chinese government’s new emphasis on conservation – in fact, conservation has been made part of the curriculum in Chinese schools; giant pandas and Siberian tigers are housed in breeding reserves; and nature reserves have been turned into tourist attractions, bringing home to the Chinese people the wealth of their natural environments. There are warning notes: in spite of massive clean-up efforts, the Yangtze is still the single largest source of pollution entering the Pacific Ocean. And the glaciers of the Himalayas, the largest ice fields after the Arctic and Antarctic, which supply the water for Asia’s major rivers — the Indus, Ganges, Mekong, and Yellow, among others — are shrinking due to global warming.

There are several firsts in this series – this is the first time that the mating habits of the snow leopard have been filmed; likewise, no one has observed, much less filmed, the courtship and mating of the giant panda before. And, perhaps most important, this is the first time a documentary of this scope has been undertaken in China.

Two further points: narrator Bernard Hill is so close to perfection that I can’s spot any flaws: he is matter-of-fact, straightforward, not so soothing as to be soporific and not so dramatic as to undercut the film itself. And, while the BBC film crews and editors still retain their penchant for “artistic” photography, it’s not as obtrusive here as in other series. (And we are thankfully spared a heavy focus on “nature red in tooth and claw,” which in other series has been a real turn-off.)

This commentary is by necessity somewhat impressionistic: this is almost six hours of documentary, with a lot of information packed into each episode. Happily, the BBC website gives short summaries of the six episodes, with pictures, and the Wikipedia entry is more detailed.

As of this writing (February, 2018), the series is available on Netflix, and is also available on DVD.

(BBC Natural History Unit/China Central Television, 2008)