Aurora White wrote this review.

Aurora White wrote this review.

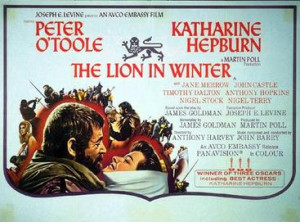

In 1968 MGM Studios teamed up with James Goldman to adapt his play The Lion in Winter for the screen. Goldman’s play had been a recent flop, running for a mere eighty-three performances on Broadway two years previously. The movie was made and was not only a success, but also breathed new interest into the stage version. I first encountered the 1968 film my senior year of high school and promptly went home to read the original script; I wanted to learn everything I could about the history and characters and mount my own production.

The title, for those of you rusty with your English history, refers to King Henry II (the lion was his crest) being in the “winter” of his life. At this point in history Henry’s kingdom stretched into France and he was in need of choosing an heir. Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry’s wife, was imprisoned in a castle (thanks to Henry who was the key keeper).

Goldman’s story is a fictional account of the Christmas court held to determine the future king. A complicated story this is, and the wit in the script combined with the actors’ stellar timing make it worth watching again and again.

Seven characters, each tremendously important, make up the cast . . . and what a cast it is. The role of the fifty-year-old (quite old for 1183) King Henry is played by a mature Peter O’Toole. Katherine Hepburn was granted the role of the spunky and vivacious Eleanor of Aquitaine. The three sons up for the throne are: Richard (Anthony Hopkins), John (Nigel Terry), and Geoffrey (John Castle). Let us not forget Alais (Jane Marrow) either, the young girl given to Henry by the French king sixteen years before to one day be the bride for the chosen king. Beyond this it is useless to explain more of the plot as it is far too complicated.

I said that the timing was crucial to the success and enjoyment one can experience with this film. While some may not appreciate a film that finds its humor through fast paced, verbal, intelligent wit with little ‘sight gags’ and no slapstick, I adore it. Each scene seems half the length it actually is because these actors are so tight in their character that they can fire one-liners back and forth without ever seeming fake or forced. One gets the sense that these conversations might indeed have occurred between Eleanor and Henry, Henry and Alais, Richard and Philip, John and Geoff.

The technical aspects of this film are quite impressive too, with period costume more accurate than those generally seen in such films. The whole movie takes place within Henry’s castle in Chinon, a vast castle in the cold of December, and the production crew made sure we feel the draft from the open spaces and cold stone. The cinematography often mirrors the long walking shots that we now see all the time (on The West Wing, for example), creating the feeling that we have been transported back centuries to drop in on this family crisis.

While this film does have some minor downfalls — Morrow’s Alais is a bit too whiney for my taste and a few gems were cut from the original text and replaced with extraneous muck (I’m still holding out for the version that leaves those gems in) — they are easily ignored and outdone by the beauty of the final work. It is no surprise that this launched Anthony Hopkins into stardom, or that so many see Hepburn (who won the Best Actress Oscar for this role) and O’Toole as the definitive Eleanor and Henry. If somehow you  have missed this piece of film history, go rent the DVD, sit back, and allow yourself to be transported back to 1183.

have missed this piece of film history, go rent the DVD, sit back, and allow yourself to be transported back to 1183.

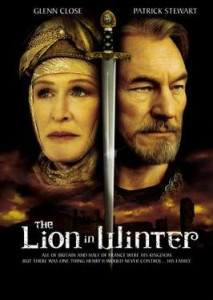

I am not a big fan of movie remakes, especially when the original was so fantastic. But every now and then someone comes along and surprises me with one that is as good as or better than the original. This was what I discovered after I watched the 2004 version of The Lion in Winter.

The script is still the same screenplay adaptation Goldman wrote for the 1968 film. The entire framework in the technical areas remained untouched. The actors were the key to bringing this new version to life. I should think it would be rather intimidating to attempt to play Eleanor of Aquitaine or Henry II after Hepburn and O’Toole. The director cast Glenn Close as Eleanor and Patrick Stewart as Henry and the choice could not have been better. Close and Stewart bring to the film a chemistry and wit that Hepburn and O’Toole never did.

With repeated viewings Hepburn’s Eleanor eventually struck me as being a little devoid of the true stoicism and sarcasm that I see the character as having. Close presents an Eleanor whose emotional indicators are much more subtle, the way the character reads on the page. Stewart, too, breathes new life into Henry’s role. He keeps up with Close’s pace and allows enough of Henry’s heart into view, rather than only his determined grip on power; we can stand by him rather than judge him too harshly.

Unfortunately, this film forgot that the story is really about the whole royal family, not simply about Eleanor and Henry. Because of this I think that the supporting cast was not really allowed to find their individual moments in the spotlight the way they do in the play and original film.

The director also, for reasons unknown, decided to skip over the tension between Philip (Jonathan Rhys-Meyers) and Richard (Andrew Howard). It is one of those little things that doesn’t seem that important to the overall piece, but really it is a massive turning point in the script and I think must be portrayed with that in mind.

Overall, the new version surprised me with just how good it was. As it turned out, my fears about the new version were unfounded, even though it was not without its own disappointments. I can fully recommend both versions to anyone who might be interested in this little bit of fictionalized history. In fact, watch them both, one after the other in either order; you won’t be sorry.

(MGM, 1968)

(Hallmark Entertainment, 2003)