Rebecca Swain wrote this review.

Rebecca Swain wrote this review.

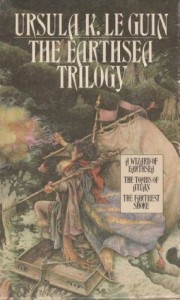

This classic fantasy series is often compared to The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien and the Narnia series by C.S. Lewis, but this is not a fair comparison. Although all three can be read as allegorical fantasies, Le Guin is concerned with different religious and philosophical issues, and her writing style differs considerably from Tolkien and Lewis. Le Guin’s trilogy possesses a quiet charm and mystical beauty all its own and is in no way derivative of the other two. These three novels are known collectively as the Earthsea trilogy, but they can be read independently. They are categorized as being for grades 6-9, but their themes are complex enough to challenge adults, and Le Guin’s writing is not over-simplified or condescending.

A Wizard of Earthsea introduces the main character of the series, Ged, as a little boy who discovers he has magical ability. He studies under his town’s local wizard for a few years, then decides he wants to learn faster, so he goes to the island of Roke, where young boys learn wizardry. While on Roke, Ged’s arrogance and carelessness lead him to show off to impress the other boys. He accepts a dare to call up a spirit and instead releases a mysterious, evil shadow from beyond this world.

The experience nearly kills Ged. When he recovers, he finishes his studies on Roke and is hired by the residents of Pendor to protect them from a dragon that has menaced them for years. While he lives there he is haunted and tormented by the shadow, and finally realizes that he must go after it instead of trying to hide. In order to fulfill his obligation to the townsfolk of Pendor he goes out to meet their dragon instead of waiting for it to come to him. Once he has defeated it, he goes in search of the shadow.

The second half of the book describes Ged’s dangerous quest for his enemy. The mysterious being sometimes leads, sometimes follows him in a dangerous chase, impersonating him in towns, luring his ship onto rocks. In the end, Ged confronts and defeats the shadow. Knowing this ahead of time does not spoil the ending; this is the kind of book that readers know will have a satisfying conclusion. The intriguing questions are what the shadow actually is, and how Ged goes about subduing it.

In this book Le Guin uses the metaphor of shadow and light to explore good and evil and the dual identity of every person. With quiet intensity she examines the idea that every action has a consequence that must be anticipated before power is exercised.

The second book is The Tombs of Atuan. It begins years after Ged’s adventures with the shadow, and the first several chapters do not involve him at all. It is the story of a little girl who is given at age five to practitioners of an ancient religion to become High Priestess and perform the rites due the Nameless Ones, gods most people have forgotten.

At first Arha (“The Eaten One”) enjoys her position as High Priestess at the Tombs. But as time passes and she is separated from the other girls who have been sent to serve various gods, she grows bored and restless, something she is afraid to admit to herself or anyone else.

When she is in her early teens she is sent through a maze under the Tombs that only the High Priestess can follow, to execute some prisoners who have committed sacrilege. She becomes interested in learning her way around these passages, and one night while she is exploring she sees a light in the corridor ahead of her. It is forbidden for anyone but her to be under the Tombs or to show light there, and she creeps up behind the intruder to see who he is.

The interloper is Ged, come to steal an object of power from the treasure room. Because he has committed sacrilege by entering the labyrinth, Arha holds him prisoner there, but feels reluctant to kill him. As time passes she and Ged grow to trust each other. The wizard has no power in that place, so he is dependent upon Arha to set him free, but several others at the Tombs know about him and want him dead. She and Ged must work together to free him from his underground prison before he is killed.

In this book Le Guin portrays Arha’s awakening spirituality and her questioning of the “truths” she has always accepted. She not only must free Ged from his underground prison, but must also free herself from the weight and darkness of the Nameless Ones and regain her identity and her name. Le Guin pursues the themes of light and shadow, good and evil, and the power of names that she introduced in A Wizard of Earthsea.

The Farthest Shore finds Ged many years older. He has become arch-mage, head of all wizards. The book focuses, however, on the other major character, young Prince Arren of Enlad. The novel is Arren’s coming-of-age story.

Arren has come to Roke to report that magic is disappearing from the world; wizards are being maimed or killed, witches and chanters are forgetting the words to their spells. The natural balance is upset.

Ged and Arren set off by sea to find the cause of the imbalance and to fix it, if they can. Their first stop is Hort Town, where they discover a wizard whose hand was cut off by the townspeople so he could no longer weave spells. He leads Ged to a place beyond reality, assuring him that this is where he will find true power, true immortality. But while Ged’s spirit is there, his physical body is in danger where it lies in the maimed wizard’s miserable rented room.

Arren saves Ged’s life but is taken captive and enslaved. In turn, Ged saves Arren, and their adventures continue as they sail through Earthsea looking for the man who is offering immortality to people who will give up their magic. Ged and Arren see peculiar sights and meet strange occupants of Earthsea, including dragons, and people who live their lives on rafts in the sea. At last they learn why magic is disappearing, and what they must do to save it.

Le Guin focuses on immortality and the importance of death in giving meaning to life. As in the earlier books, her approach is heavily influenced by eastern philosophy. She finds no value in living forever, only in returning to the earth and becoming a part of the natural world. She questions what price we pay in our efforts to prolong life, and how much we disrupt the equilibrium of the planet.

These are not action thrillers. There are adventures in the trilogy, but little violence and no sex. Any danger or suspense is included for the sole purpose of furthering the plot or illustrating a philosophical idea. Le Guin places great importance on what her characters say, so there is a lot of dialogue, but little small talk. The words, like the actions, are carefully written to further the story.

Le Guin’s interest in anthropology and ethnology contributes to the success of these novels. She creates an elaborate geography for Earthsea, only some of which she actually presents to the reader. The maps and prose descriptions increase the believability of her imaginary world. She creates convincing characters in the same way, by providing realistic details about them and the history of their various societies while giving the impression that there is more she’s not revealing. This technique fleshes out her stories, giving them depth and an air of continuity.

Le Guin’s simple, unostentatious writing style is perfect for these novels. It conveys triumphant serenity and a sense of balance shaken but never destroyed. Earthsea is a place to be visited again and again to find hope for our real world.

These books are still in print in many editions.

(Puffin, 1971 – 1974)