When I was in sixth grade, I had a crush on a girl in my class. We even surreptitiously held hands backstage at the school’s Christmas musical program. But although it was beginning to be OK to admit that you liked girls in the abstract, it was not OK to admit that you liked one particular girl.

When I was in sixth grade, I had a crush on a girl in my class. We even surreptitiously held hands backstage at the school’s Christmas musical program. But although it was beginning to be OK to admit that you liked girls in the abstract, it was not OK to admit that you liked one particular girl.

It was about that time that the song “I Think We’re Alone Now” by Tommy James and the Shondells hit the airwaves. Over the next several months it climbed the charts to become a bona fide hit, the third and biggest to that point for James and his group. It perfectly captured the clandestine nature of puppy love, and was an instant hit with the “teeny-boppers.” I certainly identified with it.

It was early 1967, and teen music was on the cusp of making the transition from rock ‘n’ roll to “rock.” I had been a huge fan of The Beatles since they first hit America in 1964, but in ’66 with Revolver and especially in ’67 with Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band they led that transition. In the process, they at least briefly left me and other young fans behind. Waiting in the wings to take their places in our hearts and on our turntables were groups like the Shondells, the Monkees, the Cyrkle, Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs, Tommy Roe, Neil Diamond and other more youth-oriented acts.

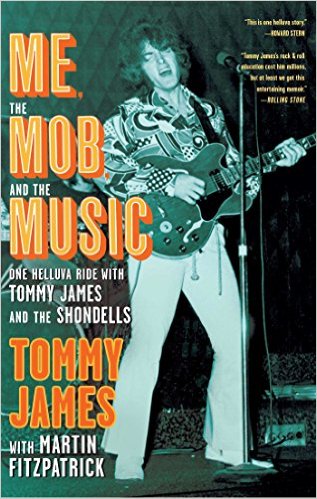

Me, The Mob And The Music is the story of how James (born Thomas Gregory Jackson in 1947) rose from his beginnings in garage bands in Niles, Michigan, to a series of Top 20 hits from 1966 through 1969. That rise was engineered by a New York mobster named Morris Levy, owner of Roulette Records, but the hits were Tommy James’s.

The British Invasion had sent thousands of teenagers across the country into their garages with guitars and drums. Tommy James was just a little more fanatical about it than most. In his telling, he was never interested in anything else. His after-school job at a record store exposed him to all the new music, and he and his friends spent hours figuring out how to play all those songs. He played in and put together a few bands, and eventually toured in parts of Michigan, Indiana and Illinois. When the opportunity arose toward the end of 1964 to record a single for regional distribution, he and his bandmates settled on a song called “Hanky Panky” from the B side of an obscure record by Ellie Greenwich and Jeff Barry (playing as the Raindrops). James and his Shondells (who were actually the Spinners, another local group) didn’t know anything but the refrain, so they made up some verses to go with it and recorded it in three takes.

The record was popular locally, but James knew he needed more than that. He just didn’t know how to go about getting it. What he got was a stroke of luck — or fate. Nearly two years later in 1966, a DJ in Pittsburgh picked it up in a thrift shop, played it on the air and it took off like wildfire. His manager heard about it and hustled the 19-year-old Tommy to Pittsburgh, where they promoted it on all the TV and radio stations, and it became a “breakout regional hit” noticed by all the trade publications. That led to a trip to New York, where they shopped it to all the major labels, and even some minor ones, and by some mysterious process ended up on Levy’s Roulette, where James stayed for the next eight years.

The book chronicles the way James cranked out hit after hit for Roulette and never saw a cent in even the meager royalties promised in his contract; his chaotic personal life in which a couple of marriages fell victim to his carousing; his survival of a major Mafia war during which Levy had to flee the country; and his eventual separation from Roulette, his cleanup and a revival of sorts. A fairly typical story of its times, except perhaps for the Mob connection. (Levy was the inspiration for the character Hesh Rabkin on the HBO series The Sopranos.)

It’s a fairly short book at just over 200 pages, for such an eventful life, but that’s as it should be. Too many celebrity autobiographies give you way too much detail when what you really want is the highlights. Me, The Mob, And The Music succeeds on that score. You get a recounting of the climb to stardom, the stories behind the main songs and albums he wrote and recorded, the sordid bits about Levy’s business practices, and fairly candid but not in-depth revelations from James’s personal life.

When I read a musician’s bio, I’m mainly interested in the stories behind the songs, particularly the writing and the recording. Most James fans know at least the outlines of the story of how the flashing Mutual Of New York sign led to his hit “Mony Mony,” but here you get the whole story. And I for one didn’t know that the version of “Crimson and Clover” that topped the charts in 1969 was an unfinished demo. You can read the book for the details. Oh, and wait until you find out just how many millions Levy swindled him out of!

Me, The Mob, And The Music is a quick read and reasonably well written. In fact, it has a number of quite nice touches, including the title (which echoes the title of my favorite James album, My Head, My Bed, And My Red Guitar — which itself is a quote from one of his later hits, “Gotta Get Back To You”) and the ending, which also quotes from another of his big hits — the one I started this review with, in fact.

Unlike some of his compatriots, Tommy James lived to tell about his life as a rock star. And it’s a pretty good tale, at that.

Scribner, 2010

Here’s “Gotta Get Back To You.”