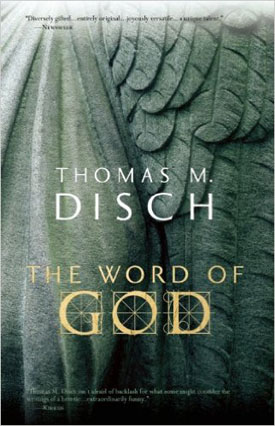

Thomas M. Disch was best known in some circles as one of the New Wave generation of science fiction writers. In others, he was known as an accomplished poet, while in still others as an incisive and iconoclastic critic. “Iconoclast” is a word that fits across the board, I think, and it’s all laid out neatly in The Word of God.

It’s hard to know how to typify this book. Memoir, in some respects. Satire, most certainly. Polemic, but we expect no less from Disch, no matter what his mode of the moment.

Perhaps it’s easiest to let Disch do most of the commentary here. He begins, quite simply and concisely, “Let there be light.” (I think we can see where this is heading already.) He goes on:

There, the word is spoken and the universe has been brought into existence, and the Enlightenment along with it. We’ll proceed from there. The important thing, always, is to have made a beginning. That’s certainly been the way when I’ve written fiction, and Holy Writ probably works the same.

One is tempted to focus on one aspect or another of this all-but-indefinable book: a satire on organized religion and those who subscribe to it (not your run-of-the-mill believer, but the “Believers” who seem to be all over the place these days); a fictionalized memoir; a not-so-gentle swipe at Philip K. Dick (revenge for reporting him to the FBI as a communist agent the day before Dick sent a letter to Disch claiming that Camp Concentration was the best science-fiction novel he had ever read?); a sampler of his poetry; sketches for other stories. But it all weaves together as it wanders around, and I somehow get the feeling that if Disch wanted us to look at it that way, we probably should, so don’t expect me to pick it apart for you. (After all, by his own admission, by this time he was a self-aware god, although fairly laid-back about it.)

And I think I’m on target there: this is absolutely a case of the whole being more than the sum of its parts. It is satirical, in a sometimes brutally mordant way, it is whimsical, it is angry, and it’s delightfully crazy. (The bit where Disch intervenes to insure his own conception is offhand, a little smug, and more than a little unexpected.)

The book has been called “extraordinarily funny,” and you can see from the beginning just where that “funny” is: it’s the tone, the makeshift, ad hoc, “I’m sort of new at this so let’s see if this works” wide-eyed feel of the whole thing. Just let yourself sink into it and go with the flow.

One word of advice, though: whatever you normally expect from God, don’t.

(Tachyon Press, 2008)