In 1983 Terry Pratchett’s first Discworld volume was published by Colin Smythe Limited (UK). It wasn’t his first novel, but it was the very first book of what is one of the longest running and best loved series in modern fantasy. Now Hill House (U.S.) has begun issuing facsimile copies of the original British hardcover editions.

In 1983 Terry Pratchett’s first Discworld volume was published by Colin Smythe Limited (UK). It wasn’t his first novel, but it was the very first book of what is one of the longest running and best loved series in modern fantasy. Now Hill House (U.S.) has begun issuing facsimile copies of the original British hardcover editions.

It’s been 23 years since Pratchett wrote The Colour of Magic. Since then he has become one of the most successful fantasy writers since the author of the Kama Sutra (Vatsyayana, self-published, 340 AD approximately). So at this date does a reviewer approach The Colour of Magic with the reverence due a classic? Does a reader look back and discern the skill, the apt satire, the deep wells of humor and humanity apparent in the nascent saga?

Nope. That would deny Pratchett the fruits of his own maturation, which are so gloriously apparent in the later books. The Discworld oeuvre is now a bronze colossus, bestriding the world, but in 1983 The Colour of Magic still had some baby fat. It’s taken time to melt it away and reveal the to-die-for cheekbones and chiseled abs of the giant.

For those who’ve never read this book (or who, like me, had forgotten it), the plot showcases the wizard Rincewind and his client Two Flowers. Rincewind is not so much a failed wizard as an impacted one. He knows only one spell, which is so powerful it has driven all other spells from his mind and keeps trying to cast itself, which Rincewind resists, due to a suspicion that the act would destroy him. Two Flowers is the first tourist ever seen on Discworld, and the havoc he wreaks in his innocent pursuit of the quaint and picturesque makes one doubt there will ever be another. It seems unlikely either Discworld or the tourist would survive.

The basic structure is of four contiguous stories. In each chapter, Pratchett satirizes some classic fantasy hero or plot. Chapter One gives us versions of Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser. Chapter Two sends up all excessively tentacled chthonic gods. Chapter Three features a quasi-Conan, a naked sorcerer queen and dragons. And in Chapter Four, Pratchett takes a shot at space programs, bureaucracy, and Big Government before literally throwing his heroes off the edge of the world. Choice stuff, this.

Mark Twain (another brilliantly funny writer) used to say that when he was fourteen he thought his father was totally ignorant; but by the age of twenty-one, Twain was amazed how much the old man had learned in the intervening years. I went through the same revelation on re-reading The Colour of Magic. I first read this book in my callow 20s, and I dismissed it as a light piece of fluff, funnier than most fantasy (a definite plus) but derivative. I was wrong.

Though Pratchett was still finding his way, he was at least proceeding cautiously through the right darkness here. There are hints of the stern sense of justice so clear in the later books. There is the hysterical trick of taking small actions to their ultimate, demented yet logical extreme. For instance, it turns out there are male dryads, as a female dryad asks primly,”Where do you think acorns come from?” This ambushes the reader on so many levels. It sounds like it makes sense, but when you try to figure out how, your mind reels. It’s a neat Latin pun. And it really makes you wonder queasily about the private lives of dryads.

There are some interesting first takes, obviously re-taken on consideration. Here, all sorcerers are skinny; ultimately, the canon has them all corpulent instead. The Assassin’s Guild is not yet an upper-class finishing school and any old homicidal maniac could join in the early days. Death is more worldly, more cynical and less noble: pressed for time (an urban plague requires his attention), he sends Scrofula to fill in on an individual demise. The Patrician is already The Patrician, but he is not yet the enigmatic Vetinari; he’s more like some Lovecraftian scion, hunched and weird and offering his guests really strange, vile seafood canapés. But overall, this is good writing. I certainly would not reject it at first reading now, and it glows with great promise in the light of what was yet to come.

Facsimile copies are wonderful, either re-uniting us with an old friend or finally letting us meet someone we always wanted to know. One of the unexpected bits of humor here is that the jacket contains blurbs for Pratchett’s novel Strata (Corgi, UK, 1988). Strata contains the idea that eventually became the Discworld, once Pratchett apparently decided science fiction was not a broad enough field for his amazing vision. (He was right, too.)

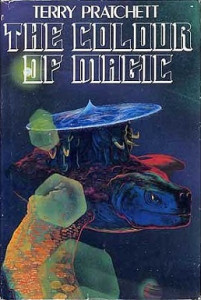

Hill House is reportedly issuing the first twelve Discworld books in these nifty facsimile editions. Great news! This first one has an extra-special cover as well, not just the Colyn Smythe, Ltd. jacket (a splendid Great A’tuin wearing the Discworld like an outré Easter bonnet) but a second, inner cover underneath. The secret book jacket is the Josh Kirby cover, from the first Colin Smythe reprint (1983). It’s the cover I remember from the first imported paperback I bought. Lovely to see it back where it belongs.

(Hill House, 2006)