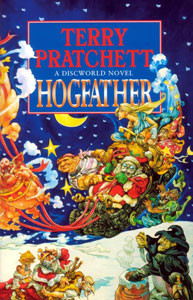

Don’t look now, but Terry Pratchett has gotten serious on us. Technically speaking, that’s not quite true – there are still plenty of laughs to be found in Hogfather, the semi-current installment in Pratchett’s Discworld series. (The US and UK release schedules for Discworld novels are a bit off, so trying to figure out which is the latest is a lot like trying to figure out the continuity of Discworld itself. That is to say, it’s best not to think too hard about it, but rather to enjoy whatever seems applicable at the time, and not to argue when something seemingly impossible happens.) It’s just that after a regrettably long dip in the quality of the Discworld books, Pratchett has taken a new, and wholly superior, tack.

Don’t look now, but Terry Pratchett has gotten serious on us. Technically speaking, that’s not quite true – there are still plenty of laughs to be found in Hogfather, the semi-current installment in Pratchett’s Discworld series. (The US and UK release schedules for Discworld novels are a bit off, so trying to figure out which is the latest is a lot like trying to figure out the continuity of Discworld itself. That is to say, it’s best not to think too hard about it, but rather to enjoy whatever seems applicable at the time, and not to argue when something seemingly impossible happens.) It’s just that after a regrettably long dip in the quality of the Discworld books, Pratchett has taken a new, and wholly superior, tack.

Discworld began as a straight-up parody of heroic fantasy, predicated on the notion that somewhere out there, there really is a flat world held up by four elephants on the back of a giant turtle (a la one of the more widely known, and ridiculed early conceptions of earthly cosmology). Of course, a world with such an absurd physics would have an equally absurd population.

Specifically, broad parodies of every beloved fantasy cliche this side of Tolkien. Our tour guides to this magical setting were inversions of the classic fantasy protagonists. Rather than a “normal” human from our earth who stumbled into fantasyland, we were instead treated to TwoFlower, a tourist from the distant, boring side of the disc (one of the early adventures involves his attempts to introduce insurance someplace where it really doesn’t belong) and Rincewind, a wizard who doesn’t actually know any spells. Topping the inversion off, instead of a magical ring, we get to meet TwoFlower’s sentient, carnivorous Luggage. (We do meet a magical sword early in the series, but it’s pretty much a whiny git – another flipping of the basic trope). Every other fantasy standard was either inverted or lampooned broadly and mercilessly.

On one hand, recognizable counterparts to Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser, Conan the Barbarian (three times by my last count), Cthulhu, the Dragonriders of Pern and more all went whizzing by for comic effect. On the other, every cliche that wasn’t lampooned was inverted. The noble wizards’ college became a collection of backstabbing, gluttonous paranoids, the shining city on the river turned into a legendary dump and so on. And for a few books, this worked very well indeed, as Pratchett rounded into form, and got comfortable with his setting and his characters. Rincewind in particular acquired a weaselly nobility, the quality of an almost-Everyman who knows he’s in over his head and still forges on despite his better judgment. However, Pratchett’s crowning achievement in characterization was death, or should I say Death. After all, it makes perfect sense for a world defined by cliche to have an actual skeleton in a black cloak gadding about collecting the souls of the recently deceased. However, the Discworld’s Death is a complicated fellow, at once an elemental force and a very human figure who’s recognized that he’s not quite human and wants to bridge the gap. Some of the best novels in the series, notably Mort, hinge upon Death’s attempts to understand the human condition a bit better, though never in a hackneyed or trite fashion. The reader truly feels Death’s confusion at these impossible creatures he’s forced to deal with, and observes his halting steps towards sympathy, if not understanding.

Unfortunately, the simple conceit of a world built on scrambled fantasy modes ultimately couldn’t sustain itself, and the series went into a lull. Books like Guards! Guards! were loaded with bumbling soldiers with amusing accents, deliberate misunderstandings, and so forth, but no real meat. They certainly were amusing and enjoyable enough, but there was little about them that was memorable, and certain of the best aspects of the Discworld eased into a sort of pleasant gentility. Unseen University, once a savage parody of the sort of wizardly college that appears in everything from Feist to Jordan, became jolly, and the wizards who once summoned Death himself to answer their questions and picked each other off with ruthless abandon seemed more interested in stuffing themselves silly and being affably Gamgee-like.

Luckily, the downward trend was reversed. Starting with Lords and Ladies, a viciously amusing take on those who would boil down faerie legend into cute elves cavorting in the garden, Pratchett once again honed the edge of his satiric blade. The novels got tighter, and while the broad and gentle gags were still omnipresent, there was a quiet edge beneath them that made individual titles stronger.

And that, in its own roundabout way, brings me back to Hogfather, possibly the finest in the series since Mort. The premise of the book is simple. Certain entities, best described as auditors of reality, get loose through some wizardly bungling and decide that the Disc’s equivalent of Santa Claus, the Hogfather (and yes, his sleigh really is pulled by pigs) needs to Never Have Been. To accomplish their goal, they hire the best the Assassins’ Guild has to offer, a charming little psychopath named Teatime (pronounced tee-AH-tim-AH, or some such) who manages to infiltrate the Tooth Fairy’s operation and pull it off. All sorts of chaos ensues, with Death filling in for the missing Hogfather in his own inimitable way, various other mythical entities inventing themselves to fill the void the Hogfather left, and ultimately, Death’s adoptive granddaughter charging off with some unlikely companions to effect a rescue of the Disc as they know it. It’s a wild romp, with a suitably high body count to amuse fans of fantasy and enough one-liners to keep those who want nothing more than a laugh rolling.

But there’s more to Hogfather, much more. That’s because the book is really the Disc’s take on all things Christmas, thinly disguised here as “Hogswatchnight.” Pratchett’s not about to let such a juicy target go by without peppering it from every angle he can. That’s not to say that Pratchett is anti-Christmas, indeed, far from it. But he clearly differentiates the spirit of the holiday from the way it is celebrated in some circles, and finds those celebrants wanting. Indeed, much of the middle of the book is devoted to skewering those who’d ignore suffering outside their own door while gorging themselves inside. Even Death himself loses some of his implacability at the sheer unfairness of it all, to spectacular effect.

Past that, however, Pratchett gives us a sublime rumination of what it means to have an archetypal figure like the Hogfather walking around, what his absence really means, and where the belief that fuels him comes from. Indeed, there are moments that have more in common with books like Holdstock’s Lavondyss or Mythago Wood than with Pyramids or Soul Music. It is unexpected and moving and utterly right for the book, in a way that it perhaps couldn’t have been right for any earlier book in the series.

Just as important is the maturation of the character of Death. Gone is the literalist of earlier books. Death has been tempered by his experiences, and he’s both subtler and kinder, but at the same time growing more majestic and archetypal. His interactions with his adopted granddaughter reflect this, shading the character and letting us peek into depths that were only hinted at before. And while some of the minor characters – the Death of Rats springs to mind – are still mere slapstick, they’re now slapstick with a purpose, playing counterpoint to the deeper, more forceful presence of Death himself. Death, it seems, has grown up, and with Hogfather, Discworld has grown up with him.

(Victor Gollancz, 1996)