Diane McDonough wrote this review.

Diane McDonough wrote this review.

Fairy tales have their roots in the far distant past, in legends and tales of survival as the heroines and heroes venture into the world, slaying demons and surviving endless trials of strength only to return home, transformed. Originally collected as a form of folk memory, fairy tales, like so many robust and earthy thought forms,fell prey to the anemia of Victorian mores and came back to life as bloodless insipid stories of passive characters acted upon by Fate.

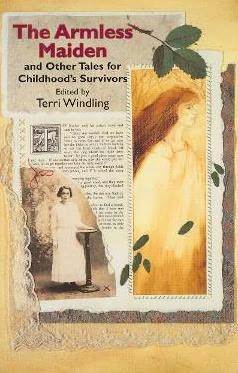

The Armless Maiden reinterprets classic fairy tales with reference to contemporary issues of childhood. In short stories,essays and poems the various authors examine the issues of confusion, fear, and, ultimately, survival.

This is a strongly cohesive collection. Windling has once again assembled the finest in contemporary masters of fantasy. This time she has a more refined goal: not just to reinterpret classic fairytales, but to extricate the subtle horrors of wicked stepmothers and over-affectionate fathers– in fact, to bring strong attention to the horrors of child abuse and our societal tolerance of these behaviours.

In the title story, “The Armless Maiden,” Midori Snyder writes an empowering and different ending to a tale with variations in cultures around the world. A young woman, mutilated and left to die by her nearest male kin, survives and is saved by the proverbial handsome prince of all fairy tales. What happens after “and they lived happily ever after” is the real story. While staying true to the original tale, Snyder uses traditional symbolism to add hope to a tragic tale.

Peter Straub rewrites “The Juniper Tree,” bringing the story of an abandoned and neglected boy into the movie star surrealism of small town America in the 1950s. As the nameless young hero struggles to make sense of his parents and his place in the family, a ragged man in an overcoat befriends him at the movies. Peter Straub brings his sinister and clever language skills into play as we wonder who is thereal hero, and more disturbingly, who is the real villain in thestory.

[Editor’s Note: Brendan Foreman informs me that, in a particularly postmodern twist, “The Juniper Tree” shows up in Peter Straub’s creepy 1988 novel Koko as a short story written by a character named Tim Underhill.]

The collection is not without humor and irony. Snow White undergoes analysis and we learn how she really felt about those dwarfs in Stephen Gould’s “The Session.” Snow muses on the effects ofher strange experiences in childhood and her relationship with her father, all the while hoping to prevent exposing her own little daughter to the same terrors. The analyst, while maintaining the careful distance of all good therapists, provides some pointed questions about the outcome of Snow White’s life.

The poetic contributions to the anthology are outstanding. Louise Gluck writes of a sister’s poignant cry for recognition in “Gretel in Darkness.” As Hansel gets on with things, living in the world, Gretel cries out in shame and sorrow at her crime — killing the witch who threatened her brother’s life.

Emma Bull details the sorrow of the witness in “The Stepsister’s Story.” The younger of Cinderella’s stepsisters, along now by the hearth, cries out for the relationship that she lost along with hertoes at that fateful fitting of the Glass Slipper.

Anne Sexton’s poem, “Briar Rose (Sleeping Beauty)” is a strong and powerful statement of the effect of acceptable behavior by fathers and uncles on young girls. Speaking of lifelong insomnia and inability to trust, Sexton relates the story of Sleeping Beauty to the numbness of women abused as children.

The essays contributed by the various authors provide thoughtful analysis, not only of the role abuse has played in the development of these tales, but the ongoing contribution of society to the denial that allows this abuse to continue. Terri Windling, especially, writes with personal knowledge of the ways children cope with ongoing neglect and abuse. Her essay focuses on the different views each child in the family has of the situation, but also on the concept of survival and the fact that awareness of events and honesty inadmitting the existence of the condition of abuse is the only way torout the evil out where it grows.

This is a strong and startling anthology of tales, far removed from the vapid tales that are interpreted as fairy tales for children. Retaining the original framework of tales from the earliest adult stories, this collection presents a moving and insightful read.

(Tor Books,1995)