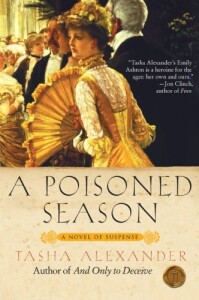

This late Victorian murder mystery’s dust jacket immediately caught my eye. It features a detail from one of my favorite paintings, Tissot’s “L’Ambitieuse” (translated as “Political Woman” or “The Reception”), depicting a dark-haired, elaborately dressed and coiffed woman gazing somewhat dreamily over her shoulder. She holds an immense fan in her white-gloved left hand. Her right arm is tucked up against the black jacket of a silver-haired gentleman, evidently her escort to whatever social event she is attending. I have actually seen the original of this painting. It is quite large and magnificent. Certainly seeing part of it on this book prompted me to pick it up and give it a look. Then I decided to give it a read.

This late Victorian murder mystery’s dust jacket immediately caught my eye. It features a detail from one of my favorite paintings, Tissot’s “L’Ambitieuse” (translated as “Political Woman” or “The Reception”), depicting a dark-haired, elaborately dressed and coiffed woman gazing somewhat dreamily over her shoulder. She holds an immense fan in her white-gloved left hand. Her right arm is tucked up against the black jacket of a silver-haired gentleman, evidently her escort to whatever social event she is attending. I have actually seen the original of this painting. It is quite large and magnificent. Certainly seeing part of it on this book prompted me to pick it up and give it a look. Then I decided to give it a read.

A Poisoned Season is Tasha Alexander’s second novel, and the second to feature her heroine and narrator, Lady Emily Ashton. In the first, And Only to Deceive (William Morrow, 2005), Emily Bromley (daughter of an earl) marries Viscount Philip Ashton, who subsequently dies under questionable circumstances while on a hunting expedition in Africa. She and her Parisian friend, Cecile du Lac, solve the mystery of Philip’s death, while Emily begins to develop an interest and expertise in classical antiquities and falls in love with the “dashing” Colin Hargreaves (that adjective appears passim in the original). While I have not read And Only to Deceive, Alexander includes sufficient back-story in A Poisoned Season to enable a new reader to pick up most of this. I reconstructed the rest by reading the Publishers Weekly plot synopsis online.

When A Poisoned Season opens, Lady Emily has recently come out of mourning and is living at her late husband’s town house in Berkeley Square, even today a very desirable London address, with Cecile as her houseguest and numerous servants to provide needed support. The season referred to in the title is indeed the London Season, that period of each year when members of the highest social classes mingle at a series of balls and parties, when the youngest females make their debuts, and when gossip spreads like wildfire among those who have very little else to do with their time. As a young, fabulously wealthy and apparently attractive widow, Lady Emily is a magnet for the attention of her peers. She challenges the social mores of the day in numerous ways, by traveling alone, by reading Homer in public places, by visiting Mr. Hargreaves at his residence unescorted, by eschewing the very tight corsets that were essential to the wearing of those hourglass gowns with their long trains.

Oh, I’m terribly sorry. It’s easy with a novel like this to get totally caught up in the actual and imagined relationships among the characters and lose sight of the plot altogether. I’ve always had much the same problem with Anthony Trollope, and this novel has some decidedly Trollopian characteristics! While at the home of a friend, Lady Emily meets a rather obnoxious man named Charles Berry. He claims to be a direct descendent of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, thus the long lost heir to the Bourbon throne. Shortly thereafter, she begins to hear about a series of so-called cat burglaries, in which all the articles stolen were (at least allegedly) once the property of Marie Antoinette. One of the burglary victims and his valet are subsequently found dead, poisoned by a lethal infusion of nicotine added to their shaving lotion. While she is busy investigating this series of incidents, Lady Emily herself is followed by a mysterious stranger who keeps leaving her messages in Greek (always conveniently translated into English for the modern reader). She also gets embroiled in a scandal that involves, not her favorite Colin Hargreaves (who is often on the Continent carrying out missions for the Queen), but Jeremy, the Duke of Bainbridge, whom she has known since they were both children. Lady Emily’s meddling mother is of course after her to remarry one of these gentlemen. Our heroine, being a liberated woman, is quite reluctant to tie that knot again.

It’s a decent mystery, sufficiently challenging, with just enough red herrings tossed about to keep the reader wondering until the last few pages who did what and why. At just over three hundred pages, it’s also a bit longer than is typical of this genre. Of course it ends happily, but there was never any serious doubt about that.

As a narrator, Lady Emily comes across as generally sympathetic and mostly believable. She’s a little too freethinking and maybe just a little too perfect, but I discovered that I could live with that. I occasionally found myself annoyed by her obsession with her clothing and her references to the gowns designed by Worth, although I am reasonably sure that Alexander added this as a touch of historical verisimilitude.

If I were to offer one criticism of the book, it would be the dearth of historical referents. Apart from Emily’s comments about having her clothing personally designed by M. Worth, who died in 1895, there are only a few other comments that enable the reader to place this story in an approximate time. One is to Henrik Ibsen’s “new” play Hedda Gabler, which premiered in London in 1891. The other is to members of the British Royal Family, specifically the aging Queen Victoria, with whom Lady Emily and her mother have tea, and occasional passing references to her son Bertie, the Prince of Wales.

Tasha Alexander may be on a roll with this series. I look forward to the next installment in a year or two.

(William Morrow, 2007)