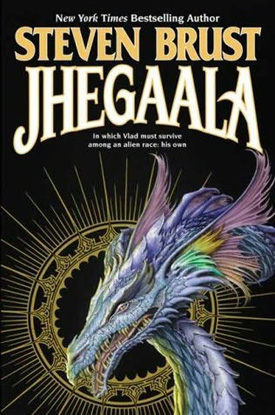

One reaches a point in any fantasy series where one wonders if the author has anything left to say. Too many of them don’t and the series peters out into another ongoing and often lame effort to feed the fans. (This seems to hold true whether the series is a true series or a Story That Wouldn’t Die, although I suspect the latter are more susceptible to this syndrome.) Happily for us, Steven Brust’s Taltos Cycle seems to have taken on a life of its own, and Jhegaala, the latest installment in the ongoing chronicle of Vlad Taltos, does, indeed, offer us something new.

One reaches a point in any fantasy series where one wonders if the author has anything left to say. Too many of them don’t and the series peters out into another ongoing and often lame effort to feed the fans. (This seems to hold true whether the series is a true series or a Story That Wouldn’t Die, although I suspect the latter are more susceptible to this syndrome.) Happily for us, Steven Brust’s Taltos Cycle seems to have taken on a life of its own, and Jhegaala, the latest installment in the ongoing chronicle of Vlad Taltos, does, indeed, offer us something new.

Vlad has traveled to the East in search of his family history – specifically, to search out his mother’s family and try to learn what he can about her. All he has are some vague memories, and very few of those, and a note that his grandfather has saved for years: an odd little thank-you note written in an ancient runic script and signed with her full name, Marishka Merss Taltos. His grandfather recalls that her family was from a town in Fenario called Burz, the site of a paper mill. And so Vlad starts off for Fenario to find a family called Merss. (And please remember that circumstances seem to favor Vlad absenting himself from the Dragaeran Empire for a while: the House of the Jhereg is still after his head. Literally.)

Arriving in Burz, Vlad finds an inn and begins making inquiries, with somewhat bizarre results: The guilds that protect and regulate each trade have become one Guild that seems to have the town in a stranglehold, and the coven that each town normally hosts is nowhere in evidence. And when Vlad starts asking about a family named Merss, people react as though he’d threatened them. He finally finds someone – a coachman – who tells him where to find his mother’s relatives, but when he arrives at their farm, they have all been murdered and the farmhouse burned to the ground. Then the coachman is murdered. And Vlad becomes distinctly unhappy with this situation, particularly after he is drugged and tortured.

One can almost see Brust stretching himself here: how, for example, do you produce a mystery with a normally very active, even peripatetic hero who in this instance is bedridden for most of the story? Vlad manages, of course, through the use of agents, some witting, most not. And while set in the Dragaeran universe, the setting is entirely new, the cast of characters a sharp break with the ongoing personalities we’ve grown used to. (And once again, there’s a coachman, a Brust motif who finds his way into widely different stories, although this marks a first appearance in the Taltos Cycle.)

And Vlad himself has added another dimension, grown more reflective, less impulsive, less abrasive (well, a little bit), perhaps, in a way, more human, less a “character” than a personality. It’s a dimension that sneaks up on you — Brust is in many ways a very subtle writer, and particularly for those who have followed the series, this is such a natural progression that it’s only in retrospect that one realizes how much Vlad has grown.

Which leads me to this recommendation: by all means read this book, but if you’re not familiar with the series, don’t start here: there’s too much you’ll miss. Go back to Taltos or Yendi or one of the other early volumes. And you’ll have all the fun of catching up.

Of course, if you are familiar with the series, feel free to dive in. The water’s fine.

(Tor Books, 2008)