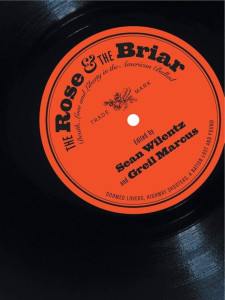

A while back Gary Whitehouse reviewed a compilation CD entitled The Rose & the Briar: Death, Love and Liberty in the American Ballad here in these very pages. It was a CD containing twenty American “ballads.” The book of the same name, edited by Sean Wilentz and Greil Marcus, features those songs (plus a couple) celebrated in literary form by … well, the publisher calls them “an astonishing group of writers and artists.” And it’s hard to argue with that description.

A while back Gary Whitehouse reviewed a compilation CD entitled The Rose & the Briar: Death, Love and Liberty in the American Ballad here in these very pages. It was a CD containing twenty American “ballads.” The book of the same name, edited by Sean Wilentz and Greil Marcus, features those songs (plus a couple) celebrated in literary form by … well, the publisher calls them “an astonishing group of writers and artists.” And it’s hard to argue with that description.

Irish poet Paul Muldoon writes new lyrics for “Blackwatertown” that at once pay tribute to the classic ballad and add new depths of meaning. See for yourself:

Who knew that my love would take me to the cleaners

When I put a few pennies in her purse?

Now when I look back on that slight misdemeanour

I see I was paying up front for my hearse.

Dave Marsh (author of the definitive book on “Louie, Louie”) traces, in fine prose, the long history of “Barbara Allen.” He quotes from the diary of Samuel Pepys, as far back as January 2, 1666, “In perfect pleasure I was to hear her [an actress named Mrs. Knipp] sing, and especially her little Scotch song of ‘Barbary Allen.’ ” He (Marsh, not Pepys) traces the development of the song into the 20th century, to a version by Bob Dylan.

Each author, singer, cartoonist, and artist who contributes to the book takes their own approach just as you might imagine, interpreting the ballad at hand, as much as they interpret the task they’ve been given. R. Crumb contributes an old comic strip and a couple of letters. These are entertaining and enlightening, both to Crumb’s personality, and to the song he illustrates. His first letter (responding to the editors’ request that he participate) says this, “Everything looked sorta interesting and, y’know, ‘Right on’ to me until I got toward the bottom of your list of ‘ballads,’ and saw ‘The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down’ by ‘the Band’ one of the most irritating pop hits of all time. Words cannot do justice to how much I hate that song. . . .” It goes on, and yet Crumb offers his two page interpretation of “When You Go Courtin’,” as well as a second letter of response, which gives Wilentz and Marcus permission to use the letters and describes his [Crumb’s] idea of good music. It’s fascinating.

Joyce Carol Oates re-writes the tale of “Little Maggie” as a first person fiction. Cecil Brown recounts the true story that led to “The Ballad of Frankie and Albert.” Singer David Thomas, founder of Pere Ubu, compares and contrasts “The Wreck of Old 97” and the Jan and Dean hit “Dead Man’s Curve.” You see that the definition of ballad is a free one, and The Band’s song might have fit. It didn’t make the cut. Whether it was due to R. Crumb’s exception or for some other reason, I don’t know. But Randy Newman’s “Sail Away” and “Louisiana 1927” are here, in an article by novelist Steve Erickson, as are The Boss’s “Nebraska,” defended by critic Howard Hampton; Bob Dylan’s “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts” and more. Each one taken on by writers as diverse as Sharon McCrumb, Wendy Lesser, and the two editors.

It’s a challenging read. I found it about equally as challenging as Gary found the soundtrack. There are lots of things to consider long after you’ve closed the cover. You may find yourself singing one or more of these ballads long after you’ve put the book up on the shelf. And it’s really that timeless quality that is the point of the exercise. If a song (and set of lyrics) has lasted nearly 400 years, it must be worth some consideration. Don’t you think? Start here.

(W. W. Norton, 2005)