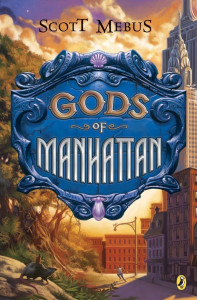

In this post-Potter world, more authors than ever seem attracted to writing for adolescents. And given the acclaim and success J.K. Rowling has achieved — including the great wealth now enjoyed by the previously struggling author — why wouldn’t more authors be giving adolescent fiction a shot? Scott Mebus joins the pack with Gods of Manhattan. He begins by borrowing the underlying concept from Neil Gaiman’s excellent novel American Gods, namely that those individuals who are remembered and perhaps even revered by a sufficient number of people live on as gods. He then moves down the shelf to liberally grab elements from the Potter series: a reluctant boy hero, with a special gift he’d gladly relinquish for a normal life with a whole and normal family; a dark, mysterious villain seeking the boy’s destruction; a magical mentor; a parallel world unseen by all but the select few. Finally the author grafts on bits and pieces from a middle school textbook on the history of Manhattan. By the end of Gods of Manhattan one sees enough threads left dangling that one or more sequels appear to be waiting in the wings. While I wish the author well, and while Gods of Manhattan has its appeal, it is not likely to rival the success of the Potter series.

In this post-Potter world, more authors than ever seem attracted to writing for adolescents. And given the acclaim and success J.K. Rowling has achieved — including the great wealth now enjoyed by the previously struggling author — why wouldn’t more authors be giving adolescent fiction a shot? Scott Mebus joins the pack with Gods of Manhattan. He begins by borrowing the underlying concept from Neil Gaiman’s excellent novel American Gods, namely that those individuals who are remembered and perhaps even revered by a sufficient number of people live on as gods. He then moves down the shelf to liberally grab elements from the Potter series: a reluctant boy hero, with a special gift he’d gladly relinquish for a normal life with a whole and normal family; a dark, mysterious villain seeking the boy’s destruction; a magical mentor; a parallel world unseen by all but the select few. Finally the author grafts on bits and pieces from a middle school textbook on the history of Manhattan. By the end of Gods of Manhattan one sees enough threads left dangling that one or more sequels appear to be waiting in the wings. While I wish the author well, and while Gods of Manhattan has its appeal, it is not likely to rival the success of the Potter series.

Overall the writing is clear, at times amusing, and on occasion even compelling. The reluctant hero, Rory Hennessy, is a loner whose father abandoned Rory’s family when his sister Bridget was a toddler. Rory’s unwelcome gift is the ability to see “Mannahatta,” the magical parallel world that shares the same space as Manhattan. He has been blocking his awareness of this gift for years until a magician hired for his sister’s birthday party causes him to awaken to it. Once he is consciously aware of this alternative reality (but fearing for his sanity) Rory seeks out the magician, who calls himself Hex, to try to understand what is going on. Soon he and his sister, whose own latent ability to see beyond the mundane is apparently given a boost by her brother’s gift, are caught up in a power struggle among the Gods of Manhattan. I’ve always disliked reviews that reveal too much of the story line and plot points, so I’ll not say too much more about what ensues. I will, however, say that the author has made a number of missteps that weaken the novel.

The first difficulty is the New York City provincialism. New Yorkers often have a tendency, given the greatness of “The City,” to assume that everyone else knows and cares more about the details of the place than they actually do. And often they also seem to think the rest of us should care about NYC more than we do. New York City is a great city and has been one for a long time. It attracts visitors from all around the world and many of its inhabitants moved there, again, from all around the world. It has a rich history and a vibrant and diverse life. This gives it a certain interest and familiarity even to those who have never been there. Nevertheless, this does not mean that the average teen reader is going to know — or care — about the likes of Hamilton Fish or Peter Stuyvesant. And it also does not ensure that readers will have a clear idea of what Central Park or Greenwich Village are actually like: neither today nor at various points of time in the past. Every story needs its setting and New York City, which has featured prominently in any number of films, television series and works of fiction, is a pretty good one; still in Gods of Manhattan the setting is at once over emphasized and under developed.

The other major flaw from my perspective is that Mebus throws everything but the kitchen sink into the mix. There are talking cockroaches who ride battle-rat steeds; there are adolescent immortals who, while they are children of Gods, are not themselves Gods; there are fortune tellers, pirates, Native Americans, and gargoyles that feed on pigeons. And I have not yet come close to exhausting the list of unusual entities that make at least a brief appearance in the pages of Gods of Manhattan. Perhaps, in the hands of a writer with the literary gifts of J.R.R. Tolkein and a thousand or so pages rather than the 300 plus Mebus has written, all of these elements could have been accommodated and given their due, but as it stands too many of these bits serve little purpose other than to add another layer of self-conscious “magic” to the proceedings.

These flaws do not totally derail the book, but they make it a less satisfying read than it might be otherwise. Truth be told, I can’t say that I’m exactly up-to-date on the overall state of adolescent fiction today. The competition may be such that Gods of Manhattan will do admirably well by comparison. Certainly the author should expect a good response from those readers who are at least reasonably familiar with NYC and its history. Rory is an engaging hero while his sister Bridget provides both a comic foil and enough pluck and spirit of her own that the book should appeal to female readers as well as males. All in all, Gods of Manhattan is well enough written, with sufficient charm and imaginative strengths that it can be recommended, even if one might wish that it better lived up to the full potential of its underlying concept and theme.

[Christopher White]

(Dutton Children’s Books, 2008)