Eric Eller wrote this review.

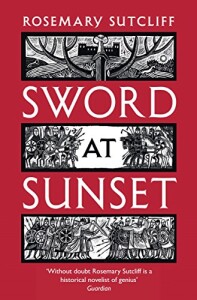

Many authors have reinvented the legend of King Arthur, but the gritty realism and emotional power of Rosemary Sutcliff’s writing places Sword at Sunset in a place of its own. Sutcliff was the first author to take the story of Arthur and strip it down to create a novel as rooted as possible in the history of the time. The resulting novel is gripping and vibrant, a powerful and fresh interpretation of the Arthurian story. From the characters to the small historical details, Sutcliff uses a talent for accurate portrayal to produce a novel that leaves you convinced that if the story of King Arthur is more history than fantasy, this must be the way events really occurred.

Many authors have reinvented the legend of King Arthur, but the gritty realism and emotional power of Rosemary Sutcliff’s writing places Sword at Sunset in a place of its own. Sutcliff was the first author to take the story of Arthur and strip it down to create a novel as rooted as possible in the history of the time. The resulting novel is gripping and vibrant, a powerful and fresh interpretation of the Arthurian story. From the characters to the small historical details, Sutcliff uses a talent for accurate portrayal to produce a novel that leaves you convinced that if the story of King Arthur is more history than fantasy, this must be the way events really occurred.

Sword at Sunset opens only hours after The Lantern Bearers ends. Unlike the earlier Roman Britain novels, Sword at Sunset is told in the first person. Narrated by Artos (Arthur) as he lies dying after Badon Hill, the story has a deeply personal perspective. Artos begins as a young cavalry commander in the army of his uncle, the British High King Ambrosius. Ambrosius’ defeat of the Saxons at the end of The Lantern Bearers has provided some much-needed breathing room. Taking this opportunity, Artos gathers a core cavalry group (soon known as Artos’ Companions) to develop into a heavy cavalry force to sweep the Sea Wolves into the sea. Before he can begin to prepare this group, he is drugged and seduced by his (heretofore unknown) sister. In Sutcliff’s story, Ygerna was abandoned and forgotten by Artos’ father. Her whole life is spent on revenging the wrong done to her mother. The seduction of Artos and conception of Medraut is the direct path to Artos’ doom and the completion of Ygerna’s revenge. After Bedwyr (combining the role of Bedivere and that of the French import Lancelot) enters the story and Artos married Guenhumara to gain much-needed troops the key elements of the legend are all in place — the fight against the Saxons, the Knights of the Round Table (the Companions), Guenhumara’s infidelity, and the fatal sin of incest that leads to Artos’ downfall.

The dark edge first seen in The Silver Branch, darker still in Frontier Wolf and The Lantern Bearers blackens every page in Sword at Sunset. Britain is nearly overwhelmed. The last Romans left twenty years earlier and the recent victories and ascension of Ambrosius to the High Kingship is only a delaying measure. He and Artos fight on, hoping that they longer they hold out, the more of their culture that will survive. Sutcliff strips away the fantastical elements and late encrustrations to provide the essence of the story of Arthur. Here is a fully human, believable Arthur. Larger than life, surely, but no more so than any other great leader. The essential elements of the story are maintained, with a core of characters to support the story — Bedwyr, Cei, Gwalchmai, Guenhumara, and Medraut. There is no Merlin, no recognizable Camelot, no chivalry or Grail quest. Artos doesn’t even become High King for four hundred pages. The focus is on the personal development of the main character within the larger struggle to maintain a civilized Britain.

One of the amazing things about Sutcliff’s writing is that she drew such vivid, physical pictures of combat. The fluidity, particularly of the cavalry charges in Sword at Sunset, is striking. You can feel and almost hear the crash of the Saxon and British armies together at Badon Hill. The emotional energy drags you up and down with Artos and his army until the inevitable final fight with Medraut. Sutcliff’s careful and detailed research, as well as her habit of writing three full longhand drafts before sending a novel to her editor, provides the texture and depth to make early medieval warfare come alive. Research was crucial — Sword at Sunset is dedicated to the horse breeding experts she consulted and the British army officer who spent a significant amount of time planning out Artos’ campaigns and (above all) Badon Hill.

There are many novelizations of King Arthur, but Rosemary Sutcliff’s Sword at Sunset stands out for its raw emotion and storyline stripped down to the essentials. The fully drawn characters sell you entirely on her version of the legend. This novel makes other versions, no matter how much fantasy and magic are injected, pallid by comparison. Other authors have recreated a gritty, “realistic” Arthur since Sutcliff introduced the idea more than forty years ago, but this first attempt at that take on the Arthurian legend still stands out as the best.

(Tor, 1987)

Eric also wrote an omnibus review of several of the other books in what became known as Sutcliff’s “Eagle of the Ninth series.” You can read an interview with Rosemary Sutcliff on the University of Rochester website, conducted several years before her untimely and sudden death in 1992, for her personal insights into writing her version of the Arthurian story.