Although he published his first story in the early 1950s, Roger Zelazny didn’t really impact the science fiction scene until 1963. That’s when I remember reading “A Rose for Eccelsiastes” in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (with their best cover ever illustrating Zelazny’s story). He followed it up the next year with the title story of this collection, which won him his first Nebula award. Zelazny and his contemporaries went on to become the American branch of science fiction’s New Wave, and pushed the envelope until it was altered beyond recognition, turning a genre of escapist literature into a potent medium for social commentary and psychological insight and a category of serious literature.

Although he published his first story in the early 1950s, Roger Zelazny didn’t really impact the science fiction scene until 1963. That’s when I remember reading “A Rose for Eccelsiastes” in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (with their best cover ever illustrating Zelazny’s story). He followed it up the next year with the title story of this collection, which won him his first Nebula award. Zelazny and his contemporaries went on to become the American branch of science fiction’s New Wave, and pushed the envelope until it was altered beyond recognition, turning a genre of escapist literature into a potent medium for social commentary and psychological insight and a category of serious literature.

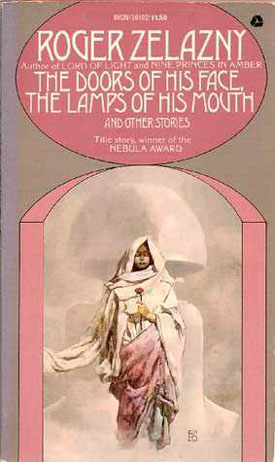

This early collection incudes fifteen stories from 1963 to 1968, what I think is a key group of works from what is arguably Zelazny’s most creative period. “The Doors of His Face, the Lamps of His Mouth” is one of science fiction’s all-time greats. The first-person narrative takes place on Venus, centered around a “fishing” expedition. It is not about fishing: it is about broken love, damaged people, hard places, and finding your soul again. It is an impressive story; beautifully crafted, inventive, rich, poetic, and painful, with the subtle and subtextual emotional resonance of Hemingway at his best.

“A Rose for Ecclesiastes” is a story likewise poetic, mysterious and painful, a gritty, emotionally realistic romance in a fantastic setting. The narrative, again in first person, relates the story of Gallinger, extraordinarily tall, extraordinarily thin, extraordinarily red-headed, and extraordinarily arrogant, who in addition to being the world’s greatest living poet is also a genius with languages, which gets him included in an expedition to Mars. He is allowed by the Martian matriarch to examine and copy some of the ancient Martian sacred writings, and to witness a performance by Braxa, the foremost of the performers of the Dances of Locar. It’s challenging on several levels, not the least of which is the understated but definite theme of miscegenation, which in 1963 was spectacularly controversial.

I can’t honestly say that these stories are uniformly excellent — some are mere sketches, some no more than one-liners, although beautifully crafted — but they are uniformly brilliant. This collection (and there are several featuring “Doors” as the title story) is worth having for the two stories described, as well as several others — “The Keys to December,” “Devil Car,” “Love Is An Imaginary Number,” in which we see one of Zelazny’s first uses of a mythological character in a non-mythological setting, “Lucifer” — are all first-rate. They may not be as earth-shattering now as when they were first published — science fiction has grown up quite a bit — but they are still pretty potent: thoughtful, probing, sometimes heartbreaking, sometimes outrageously tongue-in-cheek. Possessed of a vision that I don’t think has ever been exceeded, they sing with a kind of intensity and sheer poetry that was, and still is, dazzling.

This is one of those instances where I have to stop myself or go on for pages and pages. Let it suffice that, as I was dipping into the stories once more in preparation for this review, I found myself caught again and again by images bizarre, frightening and wonderful, less than willing to put the book down until I had finished whatever tale had caught my eye. As much of Roger Zelazny’s work as I’ve read (and at this point, I think it’s almost everything), I can’t offhand think of any better introduction.

(Avon, 1971)