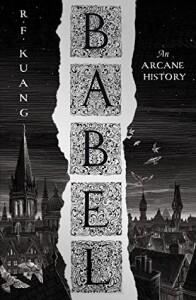

R F Kuang’s Babel is an audacious and unrelenting look at colonialism, seen through the lens of an alternate 19th century Britain where translation is the key to magic. Kuang’s novel is as sharp and perceptive as it is well written and deep, and it bears reflection upon, after reading, for today’s world.

R F Kuang’s Babel is an audacious and unrelenting look at colonialism, seen through the lens of an alternate 19th century Britain where translation is the key to magic. Kuang’s novel is as sharp and perceptive as it is well written and deep, and it bears reflection upon, after reading, for today’s world.

The word essay derives from the French infinitive essayer, “to try” or “to attempt.”

The word review is also ultimately French. Middle English reveue, from Middle French, from feminine past participle of revoir to see again, reexamine.

This is a review, and essay, where I try to attempt to talk about BABEL: Or the Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators’ Revolution, by R F Kuang.

The time and place is a very slightly alternate 19th century Britain. In this world, there is one form of magic. It turns out that silver engraved with two words in different languages that have the same meaning can derive a magical effect because no two words have the same exact meaning and that difference can be exploited.

Take the English word peak, and take the Latin word iacto. Iacto means speak, but it also means to cast, to hurl. One could use a silver bar with those two words engraved, by its magic, be able to speak more loudly, to cast one’s words out further.

The English Empire has the premier translation facility in the world and is always looking for more translators, especially in more far flung languages. As languages blend and meld, the difference between words in different languages gets smaller, and so the magical effect becomes less efficacious. Also, people need to be able to think and be immersed in both languages to make the magical silver bars function. Those silver bars do everything from improving fighting vessels to giving additional stability and robustness to carriages and railroads to providing magical healing and aid.

And so we are introduced to our main protagonist, Robin Swift. Rescued from poverty in Canton after his mother’s sickness and death, by his new guardian, Professor Lovell. He is trained in Latin and Greek, but it is in his knowledge of Chinese and English where his talents lie. The differences in translation between the two languages, in someone who has those languages so firmly in their thinking mind, provides a potential wealth of new translation pairs that the British Empire wants … and needs. And so Robin is set and polished and readied to attend the Royal Institute of Translation, the titular Babel. As Robin bonds with other members of his class at the fictional University in the city of Oxford, he soon begins to learn the cost of Empire, what Babel will do to maintain that power … and what he is asked to do to maintain that power.

Especially as what our world calls the Opium War is brewing.

And so a story is born.¹

Story. Middle English storie, from Medieval Latin historia narrative, illustration, story of a building, from Latin, history, tale; probably from narrative friezes on the window level of medieval buildings.

Having a Chinese would-be translator brought to the heart of the British Empire and his and his friends’ talents aimed toward maintaining the Imperial Project, swings for the fences in terms of themes, and this novel’s strength is in the themes it ruthlessly interrogates. Colonialism? Empire? Oppression? Racism (In fact, three out of the four in Team Babel are POC)? All of these. Two of Robin’s comrades are women, and so we get a (man’s) view to sexism as well. Kuang makes a really good point on how these toxic isms are all interconnected, intertwined and feed off of each other to produce truly terrible results. Readers of The Poppy War trilogy know that she doesn’t pull punches when it comes to the costs of War and oppression. If anything, her words are even sharper, here.

The novel is grim, dealing with some very dark subjects, and it is in the end very much not a happy story. Again, readers who have read her previous trilogy know to expect this from Kuang, but readers who are coming to her here, fresh, should learn to expect it. Are there moments of fun, of levity? Sure. Is there an absolutely bonkers level of geekery and joy in the idea and nature of translation? Does the novel take absolute pleasure in how things are translated, and what that means (above and beyond even the magic of the silver bars?) Certainly.

In point of fact, if you want to go back to the theme, then for the three POC of the four main characters², their very lives and natures are an exercise in translation. Robin is “translated” from Canton. Ramy is a translation from India. And finally, Victoire is a translation from Haiti. Those translations from their previous lives to their current ones have all gone differently, and not perfectly, either, because the whole point of the novel and the idea of translation and its magic is that while these cognate words might ostensibly mean the same thing, in reality, they do not. There is difference, divergence, and change.

And the novel understands the nuances involved. Robin gets into an argument with Professor Lovell, who is appalled when Robin seems “ungrateful” for having been rescued by him from destitution, poverty and death to a life working for Babel. Robin’s reply, aghast, is that he could have saved his mother from death – and chose not to. Colonialism and the colonial project, imperialism all degrade both the oppressors and the oppressed. And Kuang follows the logic of that, and responding to that, all the way to rebellion and revolution.

Consider the subtitle “Or the Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of The Oxford Translators Revolution.” This points to where the novel is going, which, like The Poppy War, starts off as a story of Robin escaping his previous existence, learning, and growing, and then by degrees both large and small, being thrust into taking violent, dangerous action. And, again, given that this is a Kuang book, there are costs, personal as well as societal, to taking such large scale, drastic action. In this summer of 2022 when the book is being published, given the political moment here in the United States, you bet that this novel resonates like a bell.

One thing that does disappoint me in Babel, though, and it may be an idiosyncratic affectation on my part, is what I call the “Temeraire Problem.” Temeraire is the series of Naomi Novik novels that can be high concept pitched quite accurately as “The Napoleonic Wars with Dragons”3. And while the events of the Napoleonic Wars do diverge from our own history in the writing of the novels, all the millennia of history previously, somehow, was all the same as our own. With such a major change to the world as having dragons, for world history to have gone the exact same way without discernible change seems like a failure of imagination, or a reluctance to go down the rabbit hole of what changes could and would possibly happen to the timeline. And so, really, nothing has changed.

While I can see the value of doing this for the reader, in addition to the way it reduces the ask for the reader in accepting changes beyond the high concept and its immediate consequences, it makes the world-building feel more like a copypasta of history, but with an additional added element. In Babel, we have magic, verifiable magic that has been around as long as there have been multiple languages. And yet for all that, in early 19th century Britain, everything has gone, as far as I can tell, as a carbon copy of our own world. I suppose it is possible that unseen corners of the world that our protagonist has not seen or read about, but the impression that the novel gives is that this is a Britain (and China) on the verge of the Opium Wars, and there are no complicating and entangling factors to distract from looking at that narrative as effectively as it does as outlined above. But a world where engraving silver with translated worlds is magic, there are potentially huge changes to history at a number of points that could set the entire course of history differently.⁴ And even if you didn’t want to play in super major keys with that, acknowledging how silver and translation’s magic has affected history in the past would help set up what happens in the “present” of this novel even better.

With that disappointment in mind – and again, your mileage may vary in what you expect from alternate historical fantasy – Babel is a fantastic and engaging read. Kuang interrogates colonialism, language, resistance and revolution, culture, and an underused portion of history (in genre) to sharply make her points and tell an engaging and complete story in one (relatively thick) volume. The book is, to use an overworn phrase, a levelling up of Kuang’s already honed talents from the Poppy War trilogy. Kuang is a rising talent within genre and Babel is an excellent place to discover her work.

(Harper Voyager, 2022)

###

¹It should be noted, that as befits a work that is set at an academic bastion of translation and knowledge, the book has plenty of footnotes.

²The fourth of the students, Letty, is a young woman from England. Kuang makes good use of the difference between her and her three compatriots. The rich character possibilities are not squandered, but to say more would be highly spoilery.

3Or perhaps a little more accurately and narrowly still, it’s Jack Aubrey (Master and Commander) with Dragons.

⁴Off the top of my head, societies with a lot of silver and the potential to use its magic that could have changed history in significant ways: The Athenian Empire, the Carthaginian Empire, the New World and the Spanish Empire (Kuang kind of thinks of going there but doesn’t quite manage it). Also historically, Japan traded (often indirectly) with China using silver.