Poul Anderson, who died in 2001, was one of the grand old voices of science fiction right up until his death, winning the Hugo Award seven times, the Nebula Award three times, and being named in 1997 as a Grand Master of the Science Fiction Writers of America. His was a long and prolific career. In the middle of that career, he created a character named Dominic Flandry, whose adventures had eluded me as a reader until my review copy of Ensign Flandry arrived on my desk. Now I’m wondering why.

Poul Anderson, who died in 2001, was one of the grand old voices of science fiction right up until his death, winning the Hugo Award seven times, the Nebula Award three times, and being named in 1997 as a Grand Master of the Science Fiction Writers of America. His was a long and prolific career. In the middle of that career, he created a character named Dominic Flandry, whose adventures had eluded me as a reader until my review copy of Ensign Flandry arrived on my desk. Now I’m wondering why.

Characters like Dominic Flandry used to abound in science fiction: the extremely capable “everyman” types who would rise from humble backgrounds and low military ranks through guile, bravery, and more than a little brashness to ascend lofty heights, one adventure at a time. Flandry is not unlike James Bond, as he toils in the service of the Terran Empire in the 30th century. The Terran Empire, however, is on the wane, and is coming into conflict with the neighboring Merseian Empire. The conflict in Ensign Flandry opens on Starkad, a world of vast oceans and societies that live beneath them. Here Flandry becomes involved in espionage, open war, more espionage, possible treason, life on the run from his own people, more open war — and a bit of “naughty action” on the side.

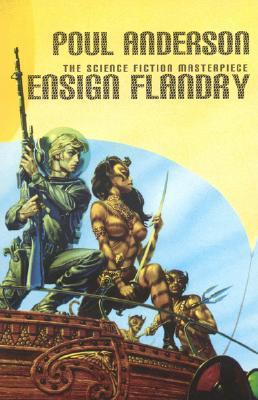

Ensign Flandry would return in a series of novels by Anderson, which I will have to look up. Anderson writes space opera that is nevertheless leavened with a good old bit of “hard SF”. He clearly gave a lot of thought to making this tale as plausible as he could. Surprising at first glance, since the cover art features a space-suited human brandishing a blaster-rifle alongside a fur-covered alien woman who is brandishing a sword as they look over the side of a wooden sailing vessel. Anderson’s use of language is also a delight; almost none of the stereotypical “SF-speak” is to be found here. For instance, in one of the opening paragraphs, Anderson writes of the Terran Empire’s ruler celebrating a birthday:

On planets so remote that the unaided eye could not see their suns among those twinkling to life above Oceania, men turned dark and leathery, or thick and weary, by strange weathers lifted glasses in salute. The light waves carrying their pledges would lap on his tomb.

Ensign Flandry isn’t serious SF, nor does it try to be. It won’t be mentioned along with such works as Dune or The Foundation Trilogy or Dhalgren as a classic of the genre. But it is an engaging space opera-meets-spy caper story that deserves to be read by readers who occasionally would like a little good old adventure in their science fiction.

(Severn House, 1966)