Deborah J. Brannon penned this review.

Deborah J. Brannon penned this review.

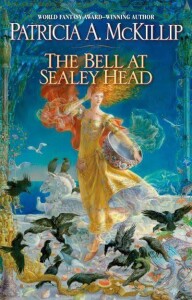

You look at the book: a woman, golden and wind-blown, spins your perception around her, a dizzying path into a sky the deep blue of the sea and down onto a wall white as bone, writhing with crows. Kinuko Y. Craft’s dream-like cover art, so inextricable from McKillip’s writings today, has your hands reaching for the book and your mind already partially intoxicated.

You open the book, flip past the title page, and read:

“Judd Cauley stood in his father’s rooms in the Inn at Sealey Head, looking out the back window at the magnificent struggle between dark and light as the sun fought its way into the sea. Dugold Cauley seemed to be watching, too, his gray head cocked toward the battle in the sky as though he could see the great, billowing purple clouds swelled to overwhelm the sun striving against them, sending sudden shafts of light out of every ragged tear in the cloud to spill across the tide and turn the spindrift gold.”

Ah, there it is. What? A domestic hook into a picturesque town? An intimation of a quiet struggle between light and dark, blindness and clarity, the true shape of things alternatively hidden and shining forth? Yes. To all of this, yes.

Patricia A. McKillip has succeeded in weaving a lovely novel, part mystery, part fairy tale, all flavored by a Jane Austen sensibility. Concerning itself with an invisible bell of unknown origin that tolls with a supernatural clarity of sound across all of Sealey Head at the precise moment of sunset, her narrative is perhaps best characterized as an enchanting waltz through the building of stories, set among this particular sleepy little fishing village with its attendant deep people and deeper mysteries.

As usual for a waltz, the pace of the novel is slow and measured. Although the resolution of the mystery is surprising and satisfying, there are no shockingly breathless moments in the tale. This is comfort reading at its best: consistent, multi-faceted, and layered, all wrapped up in McKillip’s typically intoxicating and evocative language. It’s also peopled by convincingly genuine characters, from the bookish innkeeper’s son to the deceptively shallow Lady’s daughter to the princess of a castle that exists only between the walls of a great house overlooking Sealey Head.

Perhaps, as a writer, this story was even more engrossing for me due to the interwoven commentary on the nature of storytelling and storytellers. One of the main characters, Gwyneth Blair, is a young woman writer, struggling to find time to write in the face of her family’s and society’s expectations of her: her struggle recalls the challenges faced by early female writers in our own world’s history (particularly the history of Western women’s writing). Meanwhile, the story she labors to write subtly comments upon the creation of history and fable. Deeper still in the story, there is another book and another writer, and the relationship between that book and writer tells a very differet story, a violent story, on the nature of control.

While I recommend this book whole-heartedly for reading any time of day or night, on a plane, on a train, or simply on the couch at home, here is my specific prescription for The Bell at Sealey Head: buy it, place it upon your bookshelf, and wait. Wait until a day when you feel blue, or when the world is blue around you, with stormy heavens and endless rain. Make a cup of tea, settle yourself among soft pillows and fabrics, and then enter The Bell at Sealey Head. Savor it. You’ll feel better immediately.

(Ace Books, 2008)