Pity Neil Gaiman, doomed forever to be held up as proof that comic books can be respectable literature. The barricades of academia (not to mention hoity-toity review pages everywhere) are being overrun by aggressive first-year grad students waving copies of Season of Mists and howling for the right to deconstruct the use of Australian slang in the closing panels.

Pity Neil Gaiman, doomed forever to be held up as proof that comic books can be respectable literature. The barricades of academia (not to mention hoity-toity review pages everywhere) are being overrun by aggressive first-year grad students waving copies of Season of Mists and howling for the right to deconstruct the use of Australian slang in the closing panels.

One gets a sneaking suspicion that Gaiman will become our generation’s answer to Poe: the shining light who gets hauled out to prove to the kids that the good stuff can actually be cool. Lost in all the hullabaloo, of course, is that Gaiman is a spectacularly talented author who’s tackled a wealth of media (graphic novels, short fiction in Angels and Visitations, media adaptations, children’s books and one extraordinarily well-researched history of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy) with uncommon grace, dexterity and skill. He combines a remarkable ear for memorable dialogue, a knack for sketching brilliantly eccentric characters and a genius for integrating elements of high and low pop culture into narratives that are much greater than the sum of their parts. How many other authors currently extant could make sympathetic, believable characters out of a bus-driving scarecrow, a raven, a down-on-her-luck goddess who works at a strip club, the embodied principle of destruction and a mild-mannered patch of real estate? Furthermore, Gaiman allows, nay, forces his characters to grow and change throughout their stories, a rarity in the comics world where customer loyalty is often built on feeding customer expectation.

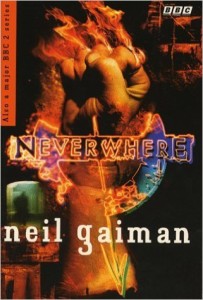

Fast forward, now, to Neverwhere, a project midway in its metamorphosis from miniseries to feature film, serving a weird sort of pupescence as a novel. Neverwhere is Neil Gaiman’s first project in traditional novel form, though anyone who thinks that writing graphic novels is easier than writing straight prose needs to be hung up by his thumbs and brutally storyboarded, and as far as first novels go, it’s an astounding success. Even if you knock off points for Gaiman’s extensive narrative experience elsewhere, Neverwhere is definitely a winner.

Neverwhere is the story of a not-quite-nebbish named Richard, who is a perfectly archetypal young executive. He’s got a suitably generic job, a suitably socially climbing fiancee and a suitably mundane existence being harried along by the demands of each. Richard’s is exactly the sort of life that could do with a swift kick of magic, and that’s exactly what he gets. On the way to dinner with his fiancee (who, honestly, doesn’t become a fully fleshed-out character until much later in the book, but manages to do so with the aid of the Monkees) and her conglomerate-creating boss, Richard stumbles across a young woman, bleeding on the sidewalk. Forced to chose between carrying on with the demands of his life and tending to the injured girl (whose name, oddly enough, is Door), Richard turns his back on society as he knows it, and takes the girl home to tend to her. What he doesn’t realize is that he’s turning his back on reality as he knows it as well. By letting Door into his life, Richard has entered her world: a world of Ratspeakers, foppish immortal assassins, angels who get wistful over Atlantis and other, more surreal entities.

What Richard doesn’t realize is that by rejecting his reality, he’s allowed it to reject him, and emphatically. He becomes a non-person, invisible to the nice normal folks around him. It is only in Door’s world of the undercity that he is a person, now, and it is to the undercity that he is forced to go. There, he joins with Door and sundry other companions in a flight from unknown enemies through the sort of heroic quest that Gaiman handles so much better than most folks these days. At the end, evil is vanquished in quirky fashion and Richard gets his choice of his old life back or a new role, an earned one, in Door’s world. Which does he take? Well, that’s why you have to read the book.

Gaiman, when he’s at his best, shares Ray Bradbury’s knack for seeing the world through a child’s eyes. His writing isn’t childish, it’s child-like, with all the wonder and terror that implies. Given a playground like Neverwhere’s half-mythical London, Gaiman gets busy. Yes, there really are Black Friars at Blackfriars, a Great Beast does prowl the sewers (with a sly nod to the urban legend of alligators in New York’s sewage system) and so on. In lesser hands, this sort of fantastic literalism could get tiresome very quickly, but Gaiman carries it off with style. His undercity is a living, breathing place, one that the reader feels existed long before the book came along and will exist long after it’s gone.

If there’s one place where Neverwhere falls down, frankly, it’s with Richard himself. The conventions of this sort of fantasy demand that the hero be a naif, but Richard is a little too naive and asks a few too many dumb questions. Yes, his world has been snatched out from under him and he’s trapped in a society he doesn’t understand the rules of, but his almost deliberate obtuseness and insistence on asking pointless, stupid questions make him more annoying than sympathetic for long stretches. The poor guy has it rough, but you’d think he’d be able to dig in his heels long enough to ask a few questions like “What’s going on? Why are those guys trying to kill me? How exactly am I supposed to survive now that I’ve thrown my life away by helping you out?” and so on. For someone who makes a heck of a sacrifice to help Door, Richard certainly gets treated like a poor relation, and he’s enough of a dishrag just to accept that. Admittedly, it’s always a necessity for the visitor from the “real world” to be shown how little he knows about his new situation, and to murmur “That’s impossible!” frequently to bring the point home, but most readers will find themselves wishing that Richard would just make the effort to deal much sooner than he actually does.

In conclusion, Neverwhere is an unlikely but solid success. Despite all the pitfalls before it: the perils of adaptation, the critical ambush that always waits for a successful authors who change forms or genres, and so on Neverwhere is enjoyable from first page to last, and mixes horror, humor and wonder in marvelous proportion. The book is a fast read, but a satisfying one, and so much sheer fun that it’s definitely a one-sitting kind of story. Just bear with Richard. He’s had a rough day.

(BBC Books, 1996)