Lenora Rose wrote this review.

Lenora Rose wrote this review.

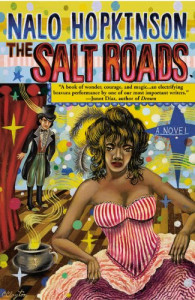

I fell utterly and blindly in love with Nalo Hopinson’s first book Brown Girl in the Ring, and I thought that love affair with her prose would continue without any blemish. It lasted through her second book without being tarnished, and through her short story collection Skin Folk with only a few minor bumps — about which I felt had to be understanding. I have yet to read a short story collection, even by an author I adore, which doesn’t have at least one story that strikes me as weak.

Nalo’s strongest point is undeniably her skill with language, bending it and stretching it until the creoles creep into your mind and feel more natural than plain English, and until the plain English beats and sparkles. There is a sharp sense of rhythm to her prose. She is also skilled at coming up with characters who are deeply organic, not built as a series of definable traits, but grown into their current shape, and growing still. Her plots are rarely so much about action as about tranformation: coming of age, coming into one’s own, becoming something new, overcoming the things which had trapped the characters in broken shells. The plots meander sometimes, but tangents in the story are invariably deeply important to the central theme, connecting intuitively to the core of things. And yes, there are clear links to folklore, myth, and faith, from a dizzying array of sources.

All that remains true of The Salt Roads, and yet I found the book occasionally dissatisfying. I could put it down, sometimes, and simply leave it for a while.

Part of this is the risk of the format. The Salt Roads is not one story so much as three tales tied together by a fourth, with hints and flashes of other stories — mostly but not exclusively African, Caribbean, or African American history or resistance — on the periphery.

This weaving-of-stories technique can make a deeply powerful work — or, sometimes, it can sap some of the strength from a thread, by breaking off at the wrong moment. It is also broken apart not by chapters, but by whole pages with a single word on them. The words are linked together in the end, into a chant, but the method of flashing the words at the scene breaks is distracting. It makes one wonder what the words actually mean at that moment (the connection is not always clear in the scene to follow, as chapter titles usually are), and effectively takes the reader out of the story. In short, the way the story is presented sometimes works against the author’s intent. It’s too easy to close the book. Nalo’s books do work best if read with the brain on, but Midnight Robber and Brown Girl in the Ring both demanded, and allowed, a complete immersion in the world of the story.

It is unfortunate, as each of the threads has much to offer in itself:

There is Mer, a slave and a healer in Saint Domingue, watching the brewing rebellion among her fellow slaves, fearful of the bloodshed and reprisals to come, though she clearly loves her people and wishes for freedom. There is Jeanne Duval, a French theatre dancer, lover of the poet Charles Beaudelaire, though they both give one another as much damage as affection. There is Meritet, a prostitute in Alexandria, longing to see the world, but sweetly naive about the world outside her tavern. The contrast between her actual course of life and the misinterpretation of it in religious text made for some of the brighter moments of the close of the book.

The linking thread is a spirit, born at the stillbirth of a baby in Saint Domingue, but first trapped in Jeanne’s mind in Paris. The spirit herself does not know her own name or nature at first. (Nalo’s own comment on this was, “I worked hard to keep it hidden, so of course the publisher put it right in the cover copy.”) She weaves back and forth through time when she can, through the three main stories, and into other scraps of history, learning about the people to whom she belongs, seeing them from the inside, trying to turn their paths toward something better. Not necessarily easier; there’s much struggle against hardship, against many kinds of oppression. The stories all seem to lead to healing, to rebuilding roads, but sometimes the end of the road is left to future generations, and the character herself hardly sees the result.

Jeanne was another stumbling block for me at first. The character was well drawn, but her world was too petty, too squalid, in part because of how she dealt with it and thought of it — Mer’s world is grimmer, but she approaches it less selfishly. Jeanne dragged down the book, as she did the spirit. Thankfully, even Jeanne’s path leads to a more satisfying conclusion, and I got to like her before the close of the book, though I felt it took too long before I could finally sympathise with her.

In many ways, The Salt Roads is less satisfying than Nalo’s previous work because it’s more ambitious. It takes a trickier narrative form, takes chances with characters and situations, leaves large parts of its conclusions ambiguous, demands that the reader make some of the connections themselves. It’s weaker than her previous books, but only because she tried to do even more with it. I enjoyed many parts of the book; the richness of words, many of the characters, the way the worlds contrasted — and matched. The many links to history. It’s a cliché to say “even a weak book by Author X is better than most books out there,” but in Nalo’s case, it remains true. I may not be as satisfied with The Salt Roads as I’d hoped, but it is still a good, flawed, book that took chances, failed at some, and won out with others.

(Warner Books, 2003)