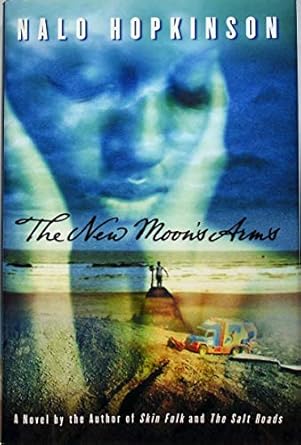

When I read it seventeen years ago, I thought of this as Hopkinson’s most accessible novel. Rereading it, I asked myself why. Perhaps the environment is less strange than her mid- and post-apocalyptic futures in which we experience the worm’s-eye view of change. This is less science fiction than women’s fiction with magical realism elements. The New Moon’s Arms takes place on a more ordinary imaginary Caribbean country made of islands, hurricane-beset, suffering the predations of big business and the world banks that pander to them to the detriment of struggling little nations.

When I read it seventeen years ago, I thought of this as Hopkinson’s most accessible novel. Rereading it, I asked myself why. Perhaps the environment is less strange than her mid- and post-apocalyptic futures in which we experience the worm’s-eye view of change. This is less science fiction than women’s fiction with magical realism elements. The New Moon’s Arms takes place on a more ordinary imaginary Caribbean country made of islands, hurricane-beset, suffering the predations of big business and the world banks that pander to them to the detriment of struggling little nations.

Yet there’s the cashew farm where the protagonist Calamity grew up. The farm is novel and miraculous not because it was obliterated by a hurricane years ago, and suddenly manifests in Calamity’s back yard. The magic is in the cashew trees, bowed to the ground with monstrous ripe yellow and red fruit, with their little false seeds dangling below like the genitals of putti. The fruit grows and ripens and falls splashingly to the ground, sweet and pungent with an odor that I, an American Midwesterner, can’t imagine. The trees are short and grow so densely that inside the grove is dark as night, dry leaves rustling, heavy fruit falling with liquid thumps all around, their branches harboring great pink squawking birds, as well as the sorts of miracles one might more usually find in a fantasy novel.

Main character Calamity is a glorious mess. She’s bang-halt bitchy, attacking first before she can be hurt or insulted, blurting out impassioned and cringeworthy diatribes against bisexual men who might steal the love deserved by some woman, or even contaminate children. But I like her. That’s a writerly feat in itself. Maybe I cut Calamity extra slack because menopause is bestowing a magical power on her, returning one to her, in fact, because when she was a young girl she could find lost things. Now she’s finding again: stolen treasure, a mermaid’s child, and the truth about her long-lost mother. She often acts like a horse’s ass, but she has a sense of fairness that drives her to mend her own meannesses that she can’t quite blame entirely on “power surges” and raging hormonal imbalance. I first read this book when I was going through some of those extraordinary transformations myself, so I feel for her. In spite of herself, I’m on Calamity’s side.

Calamity thrashes her way across the landscape of her islands, alternately battling and embracing her bad-girl history that tries to define her, recognizing almost too late the fresh opportunities to redefine herself presented after her father’s death. At the same time, Hopkinson’s islanders struggle like ants with the affairs of ants, surrounded by the sea, infinitely powerful, eternally beautiful, impenetrably mysterious.

But what I remember most, after waiting nearly twenty years to reread this book, is the cashew farm, and the repeated shocks of confronting objects out of one’s past, shocks so potent that the reader walks with Calamity through layers of jumbie fog that strip the years off her and then slather them back on, step by step by step. Who are you? Who were you? Who do you want to be? How free are you to change while you are surrounded by persons and things that slap you over and over with your mistakes and with the justifiable, cruel rage of your unforgiving victims? Are you redeemed if the public loves you, or if one person, in secret, is grateful to have known you?

If you’ve been interested in plunging into Hopkinson’s past-present-and-future Caribbean worlds to meet her wildly mingled characters, get your feet wet on creole idioms and speech patterns that still allow you to keep up with the pressure of events and the rich play of character on character, this is a good place to start. I find her work deceptively easy to read. Everything I meet is new and strange, yet I feel comfortable. She won’t let me fall. Start with this book and its powerful and identifiable heroine. I think you’ll like it.

(Warner Books, 2007)

_____________________

Jennifer Stevenson can be found on Facebook, at her website, and at Book View Café.