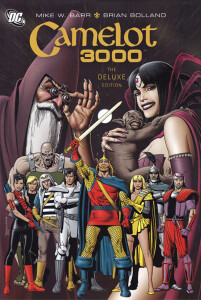

You can’t look at Camelot 3000 strictly on its own merits, whatever those merits might be. Someone coming to first read the series now – recently re-collected in a gorgeous hardcover deluxe edition by DC – would probably see it as hokey, heavy-handed in places, and a bit too abrupt to really do its narrative justice. All of that may be true, and yet it misses the point, as Camelot 3000 is one of those series that is at least as important for what it signified as for what it is. In a real sense, it’s a landmark in modern comics history, and no reading of it can do it justice without awareness of that fact.

You can’t look at Camelot 3000 strictly on its own merits, whatever those merits might be. Someone coming to first read the series now – recently re-collected in a gorgeous hardcover deluxe edition by DC – would probably see it as hokey, heavy-handed in places, and a bit too abrupt to really do its narrative justice. All of that may be true, and yet it misses the point, as Camelot 3000 is one of those series that is at least as important for what it signified as for what it is. In a real sense, it’s a landmark in modern comics history, and no reading of it can do it justice without awareness of that fact.

Originally published in 1982 (and wrapping up in 1985), Camelot 3000 was a landmark on numerous levels. The first finite run “maxi-series” DC published, it explored territory that, in the early ’80s, was not common ground for any mainstream comic book: gender roles and sexuality, the morality of treatment of prisoners and the ultimate self-sacrifice. All of this was wrapped up in a rollicking science fantasy tale of King Arthur and his knights coming back to save Earth from an alien invasion secretly sponsored by the dread Morgan Le Fay.

The story itself is deceptively simple. In the year 3000, Earth finds itself fighting a losing war against an implacable alien enemy, in part because the world government has turned completely insular (among other things). In this hour of the world’s darkest need, the symbolically named Thomas Prentice manages to awaken the slumbering King Arthur, whose destiny it is to save the world. With the help of the ever-lurking Merlin, Arthur summons the souls of the core knights of his round table, who have been reincarnated again and again through the centuries awaiting the call.

Except, of course, there are some problems. Reincarnation is a tricky business, you see. Sir Percival’s soul is born into a body about to be transformed into a hulking, mindless “Neo-man,” and there’s nothing anyone can do about it. Sir Tristan comes back in the body of a woman, which was not quite what the noble knight had planned. And other souls come back, too, including Arthur’s villainous bastard child Mordred, who’s got his own plans – and powers. With enemies from beyond the stars, a Round Table vastly different from the one he expected, and betrayal of all kind – including that eternal love triangle with Guinevere and Lancelot – can Arthur do better this time around? Or will his new Camlann doom all of humanity, and not just Camelot?

On top of the story are the reasons Camelot 3000 is so important in the history of the field. Rather than just focusing on swordplay, lasers and witty banter, Bolland and Barr unapologetically took on issues that other comics of the time would have run away screaming to avoid. Rather than take the easy way out on the issue of Tristan’s gender switch and confused sexuality, Barr laid out that there was no easy, juvenile way to resolve the issue. If Tristan accepts the love of the adoring Prentice and comes to grips with the fact that he’s now a woman, then we have explicit acceptance of a transgendered figure. If Tristan instead reunites with the reincarnation of his beloved Isolde, then the situation resolves with a mature, loving lesbian relationship – again, something one was not likely to see in mainstream comics at the time.

So much for history lesson. Is it any good? The answer is, with an awareness of what it is and where it came from, yes. The book itself is gorgeous, with Brian Bolland’s vibrantly ’80’s art practically leaping off the page. The colors are strikingly bright, appropriate for a tale of legendary derring-do amidst the stars. As for the story itself, for all that twenty-five years of advancement in comics narratives will make the modern reader see where Camelot 3000‘s plot creaks or rushes or misses opportunities, the fact remains that it is still unmistakably enjoyable, breathtaking in its ambition and lightning-fast in its pacing. Read it and enjoy it, not only for what it was, but for what it is.

(DC, 2008)