The moment I opened this book about Mike Scott and started reading it was when I first realized that it was a memoir. And if you’ve read many musicians’ autobiographies, you’ll know why my heart sank. “Oh, great, another slog through a couple hundred pages of mediocre writing at best.” It didn’t take long for Mr. Scott to dispel that notion. And when I reached the end of Chapter 1, I said out loud, “This guy can really write!” Not just songs, but prose, too.

The moment I opened this book about Mike Scott and started reading it was when I first realized that it was a memoir. And if you’ve read many musicians’ autobiographies, you’ll know why my heart sank. “Oh, great, another slog through a couple hundred pages of mediocre writing at best.” It didn’t take long for Mr. Scott to dispel that notion. And when I reached the end of Chapter 1, I said out loud, “This guy can really write!” Not just songs, but prose, too.

And if you’ve heard some of Scott’s best songs, particularly his best-known, “Fisherman’s Blues,” you’ll recognize that as quite a compliment. That song was the title track of the fourth album by Scott’s band The Waterboys, and represented a major change of direction. The style of their first three had been dubbed “the big music” after its sound and the title of a single from their second release A Pagan Place. It was similar to the sound perfected a few years later by U2 – big soaring, electric anthems and ballads. Scott and the band went through a number of what can only be described as sea changes during the three years it took to complete Fisherman’s Blues, including moving from London to New York and back again, then splitting up for a time and coming back together in a new form on the West Coast of Ireland, where they recorded many of the album’s key tracks at a rented manor house outside of Galway. The opening verse of the title track represents Scott’s frame of mind as he left New York and a disastrous love affair behind:

I wish I was a fisherman / tumbling on the sea / far away from dry land / and its bitter memories / casting out my sweet line / with abandonment and love / no ceiling bearin’ down on me / save the starry sky above …

The various iterations of the band that he put together for the sessions in various places over three years was nearly all acoustic, save an electric bass. Its core was Steve Wickham on fiddle, Anthony Thistlethwaite on sax, mandolin, harmonica and more, Trevor Hutchinson on bass and Martin O’Connor on accordion, with more drummers than Spinal Tap. The record threw everybody a curveball and divided both critics and fans because it represented such a change in direction. But it went on to be The Waterboys’ biggest seller and a landmark in international rootsy folk-rock.

The story behind that album is the centerpiece of this engaging and entertaining (if you love books about music and musicians, which I do) memoir, whose main story fills nearly 300 pages. Scott, born in Edinburgh at the tail end of 1958, started out in Edinburgh’s punk scene in the ’70s before moving to London in the early ’80s, where he formed The Waterboys in 1983. He barely touches on his family life in this book, either with his mother before leaving home or with a succession of girlfriends and wives down the years. His focus is on the growth and changes in his own life and the way that was reflected in his music.

And that’s really where he’s at his best, as in this passage in which he discovers a new passion for roots music:

As a teenage rock ‘n’ roller I’d considered Scottish folk music a hinterland of kilted buffoonery. Now I heard it anew, and the music I was in love with was the music of my own ancestors. In the bloom of their youth on the Isle of Mull my great-grandparents themselves might well have shaken a leg to ‘The Fiddler’s Frolic’.

Some of the most lyrical passages are in his descriptions of the West Coast of Ireland, including this one, as he is introducing Thistlethwaite (whom he refers to as Anto or The Human Saxophone) to Inishmoor, one of the Aran Islands off the mouth of Galway Bay:

Nowhere was there anything soft or rounded on which the eye might rest, nor any familiar shape or suggestion of conventional beauty. And the scale was all wrong: it was too large, as if a tribe of giants had abandoned the place.

Although it’s not in any way a tell-all, Scott doesn’t shy away from revealing his own blind spots and mistakes as he suffers the vicissitudes of a musician’s career. Following the success of Fisherman’s Blues, things fall apart and Scott goes solo for a while. He continues to change styles, from solo singer-songwriter to hard-rock band and back to a small folk-rock ensemble. A fairly sizeable section of the book covers his years-long spiritual quest, as he seeks meaning, community and solace in a quirky Scottish commune, but he’s always careful to avoid preaching. As the book ends he and his reunited bandmates are soldiering on in their quest to balance their fans’ desire for something familiar and their own need to follow the muse.

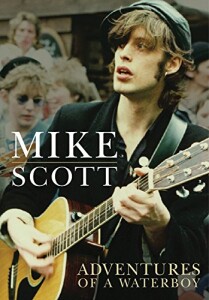

Adventures of a Waterboy is a rarity among musicians’ memoirs. It’s well-written, well-edited and well-organized, with a clear story arc and plenty of juicy details of a life in rock and roll. The book is handsomely designed with enough photos to identify key faces and places, on good heavy stock and sturdily constructed. But most importantly, it’s a smashing good yarn.

(Jaw Bone, 2012)

See Stephen Hunt’s extensive review of the recordings of The Waterboys and Mike Scott from 1983 to 2000.