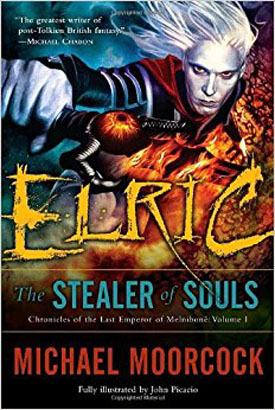

Volume 1: The Stealer of Souls

Volume 2: To Rescue Tanelorn

Volume 3: The Sleeping Sorceress

Volume 4: Duke Elric

“Michael Moorcock.” Say that name three times at the dark of the moon and you will undoubtedly summon the spirit of contemporary heroic fantasy noir, most likely in the form of a tall albino sorcerer-king wielding an unholy black sword.

“Michael Moorcock.” Say that name three times at the dark of the moon and you will undoubtedly summon the spirit of contemporary heroic fantasy noir, most likely in the form of a tall albino sorcerer-king wielding an unholy black sword.

Beginning with his Elric stories of the 1950s, Michael Moorcock took the boundaries of postmodern heroic fantasy a step farther than either Robert E. Howard or Fritz Leiber, creators of the genre as we recognize it today, had done with their heroes: the drug-ridden, demon-haunted, neurasthenic albino sorcerer-king was beyond what even Leiber could have envisioned as a hero: Elric is not only an anti-hero, but in a very real sense a tragic hero as well.

Moorcock as a writer is not all that consistent, nor is “tight” a description that I think can be affixed to most of his fiction. I’m willing to make allowances. I’ve been reading Moorcock for a long time, and so I have a sense of the overall shape of his fantasy works, from the individual series about Corum, Hawkmoon, Erekosë, von Bek and other avatars of the Eternal Champion to the ways in which Moorcock has linked them together into an overarching saga. This series of collected stories in many ways puts a foundation under the whole thing: Elric is the Ur-hero. (To give an idea of the scope of Moorcock’s vision, the complete Eternal Champion cycle, as published by White Wolf in the 1990s, at that time amounted to fifteen substantial volumes — and Moorcock has not stopped adding to it.)

This series of Moorcock’s stories constitute what he has called the “definitive edition.” The stories are offered in the order originally published, along with essays and articles by Moorcock and others that further illuminate Moorcock’s thinking on Elric and fantasy in general at the time. The individual volumes are also graced by new illustrations by John Picacio, Michael Wm. Kaluta, Steve Ellis, and Justin Sweet, as well as forewords by Alan Moore, Walter Mosley, Holly Black, and Michael Chabon, and introductions by Moorcock himself, which serve to set a context on the stories in each volume. The timeline runs from the first stories in the late 1950s (Stormbringer, actually a novella) to the script for the comic series Duke Elric (1997-98) and “The Flaneur des Arcades de l’Opera,” first published in The Metatemporal Detective (2008). Although other avatars of the Eternal Champion do make appearances, the focus is Elric. This series, then, is as much an historical document as anything else, but the meat, of course, is the stories.

To set the stage, the epic begins with the fall of Imrryr, the Dreaming City, the last city of Melniboné, which had ruled the world for ten thousand years, until younger nations rose and Melniboné’s empire shrank. The invading fleet of the Younger Nations is led by Elric, the empire’s last king, who will either have his throne back from his usurping cousin, Yyrkoon, or destroy it. The invasion is successful, the city is sacked, and while most of the invading fleet is destroyed by the empire’s Dragon Lords, Elric escapes, although not without consequence: Cymoril, Elric’s cousin and betrothed, is killed when Yyrkoon throws her onto Elric’s soul-eating black sword, Stormbringer (which also appears in various guises throughout the cycle). And then begins Elric’s long series of adventures.

The story of Elric can to a certain extent be summarized as “the search for Tanelorn,” the eternal city that sits at the center of the multiverse. The multiverse is a concept that Moorcock introduced into fantasy, and although he’s not the first to play with the idea of parallel universes, he’s the one who seems to have had the most influence: I’ve run across the concept, and the name, in the work of other writers. It’s become, for some, part of the toolbox. Elric’s problem in “finding” Tanelorn — and I must point out that the search is metaphorical, since Elric knows where it is (after all, his good friend Rackhir the Red Archer, who appears in “To Rescue Tanelorn” (Vol. 2) as well as The Sleeping Sorceress (Vol. 3), lives there) — is that to live in Tanelorn, one must give up all other allegiances. Elric serves the Duke Arioch, a powerful Lord of Chaos, although Arioch can be a fickle master: as often as not, the aid in time of need that is Elric’s return for his service is wanting. Arioch is too busy, distracted by events on another plane, or just doesn’t feel like it. It might seem an easy choice, but Stormbringer, which itself is an instrument of Chaos, is what’s keeping Elric alive. He feeds off of its power.

The concept of Balance, the necessary equilibrium between Law and Chaos, is another one that Moorcock has made his own, and it’s central to the cycle of the Eternal Champion as a whole. The dynamic of the multiverse is the constant struggle of one or the other for precedence, for an edge; the key, of course, is that neither can be allowed to triumph.

These are the two central concepts in the fantasy writings of Michael Moorcock, and both make their appearance as primary elements of the Elric stories, the one — Balance — openly, the other by, as yet, inference. Elric’s own adventures traversing the planes are more plainly told in later stories, particularly The Albino Underground, which also gives a good take on what this can mean for questions of identity as well as time and space.

In terms of how this applies to the stories in these four volumes, think of it as a substrate, the ground on which the stories are built. I’m not saying that Moorcock started off with these concepts in place — that would be ridiculous, and it’s a claim that he never makes himself. He built them as the cycle developed, which is probably why their existence seems so organic. It’s also worth noting that it wasn’t until fairly late that Moorcock looped around and brought Elric himself into the cycle as an avatar of the Champion, but it’s an acknowledgement of that organic quality that he could.

As for reading pleasure, it’s here, in abundance. There’s a certain “period” quality to the diction in a lot of these tales, intimations of the “high heroic” of Howard and even Tolkien, but these aren’t as “talky” — as concept-ridden — as later books. And Moorcock’s imagination was never lacking — he always seems able to come up with a new species of weird. In fact, add these to our list of winter reading recommendations.

(Del Rey Books, 2008)

(Del Rey Books, 2008)

(Del Rey Books, 2008)

(Del Rey Books, 2009)