I can’t even guess how many editions of The Brothers Grimm there have been printed since the Victorian Era. Hundreds would be a safe guess, but if I’d add in the various chapbooks and the like that printed illustrated versions of just one tale or another, it’d easily be over a thousand. Amazon lists some 150 editions of books which have the Brothers Grimm, but a goodly number of them are of a literary criticism nature, including Jack Zipes’ The Brothers Grimm: From Enchanted Forests to the Modern World and my favourite Zipes work on fairy tales, The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales. Our private library has hundreds of illustrated children’s books and tales for adults which either are retellings of a Grimm tale such as ‘Snow White’, or more radical updatings like Tanith Lee’s Red As Blood or Tales from the Sisters Grimmer. ‘Tis rather safe for me to suggest strongly that The Brothers Grimm in large part created the modern literature of the fantastic in the English language, as their impact has, in me opinion, been more considerable than any other single source.

I can’t even guess how many editions of The Brothers Grimm there have been printed since the Victorian Era. Hundreds would be a safe guess, but if I’d add in the various chapbooks and the like that printed illustrated versions of just one tale or another, it’d easily be over a thousand. Amazon lists some 150 editions of books which have the Brothers Grimm, but a goodly number of them are of a literary criticism nature, including Jack Zipes’ The Brothers Grimm: From Enchanted Forests to the Modern World and my favourite Zipes work on fairy tales, The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales. Our private library has hundreds of illustrated children’s books and tales for adults which either are retellings of a Grimm tale such as ‘Snow White’, or more radical updatings like Tanith Lee’s Red As Blood or Tales from the Sisters Grimmer. ‘Tis rather safe for me to suggest strongly that The Brothers Grimm in large part created the modern literature of the fantastic in the English language, as their impact has, in me opinion, been more considerable than any other single source.

(And costly to collect too — a 1909 edition published the Constable & Company Ltd. in London of Brothers Grimm, with illustrations by Arthur Rackham will set you back eight thousand dollars!)

Me favourite edition — prior to this one — is Zipes’ The Complete Brothers Grimm, which somehow we’ve never reviewed, so I’ll correct that oversight shortly.* Printed in 1987, the translation by Zipes is generally considered the best that it had been done of every tale that the dear Brothers had included in their original German language collection, Kinder-und-Hausmårchen (Children’s and Household Tales). It’s fairly rare in hardcover, but a trade edition’s still in print according to Amazon.

Now keep in mind that what you will like may or may not be what I like. For example, Maria Nutick, our Book Editor, is bored silly by Tatar! If you’re looking for all two hundred and forty-two of the tales, including the thirty-two commonly omitted tales, you must get Zipes’ The Complete Brothers Grimm, as Tatar, like almost all other translators, selects a mere handful of them to reflect her tastes, forty-six for this collection, with nine of them being for adults, more with female protagonists than not. Now keep in mind that by contemporary standards of the present day, all of the original Kinder-und-Hausmårchen would have scared more than a few children straight into whatever therapy their parents thought would help — cannibalism, incest, murder, and perhaps a taste of children’s’ flesh were all in the tales as originally written down by the ever so well named Brothers Grimm. And keep in mind that Tatar favours in her annotations a post-Fruedian spin that you might well find annoying — as I did from time to time — but she’s no worse than Angela Carter was in her interpretations of the Brothers Grimm, such as her play, The Company of Wolves. which was made in the 80s into a very weird film starring (among others) Angela Lansbury and David Warner!

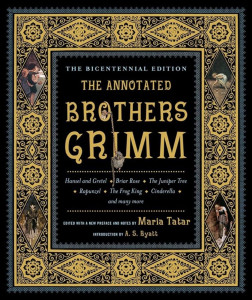

All of the Annotated books from Norton measure roughly nine inches wide by ten inches tall, making them books that stay open easily on a lap. With handsome dust jackets and generous illustrations throughout, they are a feast for the eye as well as for the mind. As Our Editor said in his review of the The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales that Tatar edited:

So what do we have so far? Good tales? Yes. Great design? Yes. Interesting artwork? That too. Annotations to enlighten the inquisitive amongst us? Oh, yes. Anything else? Yep. Her introduction’s well-worth reading for her Jungian take on fairy tales, a subject that she has covered in-depth elsewhere (see our review of Grimm’s Grimmest). She tosses in biographies of authors such as the Brothers Grimm, and of collectors like Australian Joseph Jacobs. Illustrators get their deserved coverage, too, with looks at Edward Burne-Jones, Gustav Doré and Maxfield Parrish, to name but a few. There’s an appendix of variants on the tales told at the front of this collection — odd, but charming. Following that are nearly twenty-five pages of Walter Crane’s illustrations — a sweet treat indeed! But a darker treat, too — think of them as very dark fantasies and you’ll get the tone of them.

Everything he said in that review applies here, but there’s a caveat for this collection that does not apply to the more generalized collection of fairy tales — this is not as good a collection as the Zipes collection in terms of completeness or in avoiding getting caught up in over-interpreting the tales. But it is a better collection from both a design viewpoint and for giving you a better appreciation of where the tales came from, how the Grimm Brothers edited them according to the sensibilities of their era, and what has happened to the tales in the two centuries since their time. Maria Tatar, who is dean for the humanities and John L. Loeb Professor of Germanic Languages and Literatures at Harvard University, obviously, as does Jack Zipes, knows her Brothers Grimm on an intimate level that makes her interpretations — and they are interpretations, as are all translations, no matter how accurate they are — very different from the others. Tatar’s collection is better from a storytelling perspective, as indeed I can see a storyteller late at night reading from it, but the Zipes is better as a collection simply because he avoids getting bogged downed in explaining the tales.

So I suppose in the end me only possible answer for as to which is better is, neither. Both of these collections will stay here in our library as both are useful in their own way. I should note that the introductory essay by A.S. Byatt in the Annotated Brothers Grimm is well worth your time, as is Tatar’s essay on reading the Grimm’s Children’s and Household Tales. She has an excellent bibliography, which Jack does not, but he has superb notes on where he found the original German versions of the tales he translated. She does her translations of the prefaces the Grimms did to their first two editions, which makes for interesting reading.

(Norton, 2004)

* Unfortunately, it looks like Jack never got ’round to this, or if he did it’s still lost in the Archives.